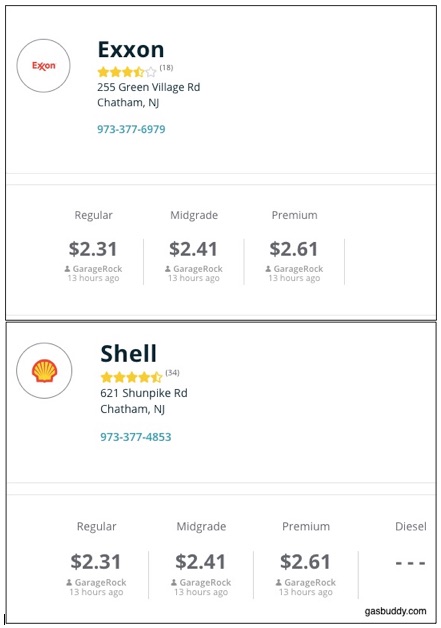

My Shell gasoline station is located across the street from an Exxon. You can see they charge the same prices:

Sort of like R2-D2 and C-3PO, their communication could depend on their artificial intelligence (AI).

Gasoline Prices

We could say that gasoline pricing algorithms are fast learners. As market conditions change–even the weather–they do too. Processing past and real time data, they quickly respond with updated prices that maximize profits. The question though is what happens when they are across the street or next to each other.

This is where it gets interesting.

In a recent study, economists looked at the impact of AI algorithms on gasoline prices. Their goal was to assess the impact of the algorithms that compose artificial intelligence. To gather data, they looked at three kinds of markets in Germany. The first had always existed. Humans did all the pricing. However, after 2017, many gasoline stations adopted algorithmic pricing software. As a result, there was a second kind of market in which one station was human but its neighbor had the algorithm technology. Then, the third was entirely algorithmic. Two competing gasoline stations each used software to price their gasoline.

Overall the new software increased profits for all stations that adopted it unless they already had a monopoly. The real difference was for two competing stations. When both let the technology determine pricing, mean margins (the difference between wholesale and retail prices) was 30 percent. But it did take time. Researchers hypothesize that it took the algorithms a year to learn the collusive tactics.

Our Bottom Line: Adam Smith

In a seemingly chaotic economic world, an eighteenth century teacher of moral philosophy created order. His name was Adam Smith (1723-1790), his book was The Wealth of Nations (1776), and his order came from an invisible hand. The invisible hand just nudged each of us to behave rationally. The incentives that encouraged consumer behavior were very different from what businesses responded to. But still, when the two interacted, a mutually acceptable price was formed and both groups emerged satisfied.

Smith believed that consumers and business would control each other if government regulation was minimal and business collusion was prohibited. But Adam Smith did worry about people of the same trade meeting together:

Today, he would have warned us about algorithmic collusion.

My sources and more: Thanks to Cary for showing me the WSJ Overheard column. Sort of hidden on the back page, it frequently has a tasty tidbit of news. So, I was delighted when they linked me to this paper on algorithmic pricing and competition. Of course it also made sense to go to gasbuddy.com to check gas prices.

Our featured image is from WSJ.