The life of a Japanese 10,000 yen note began on a Himalayan hillside. Starting as the stripped, beaten, and dried bark from a wigeli shrub, it traveled almost 3,000 miles to a Japanese printing press:

Japan still likes its cash.

Japanese Cash

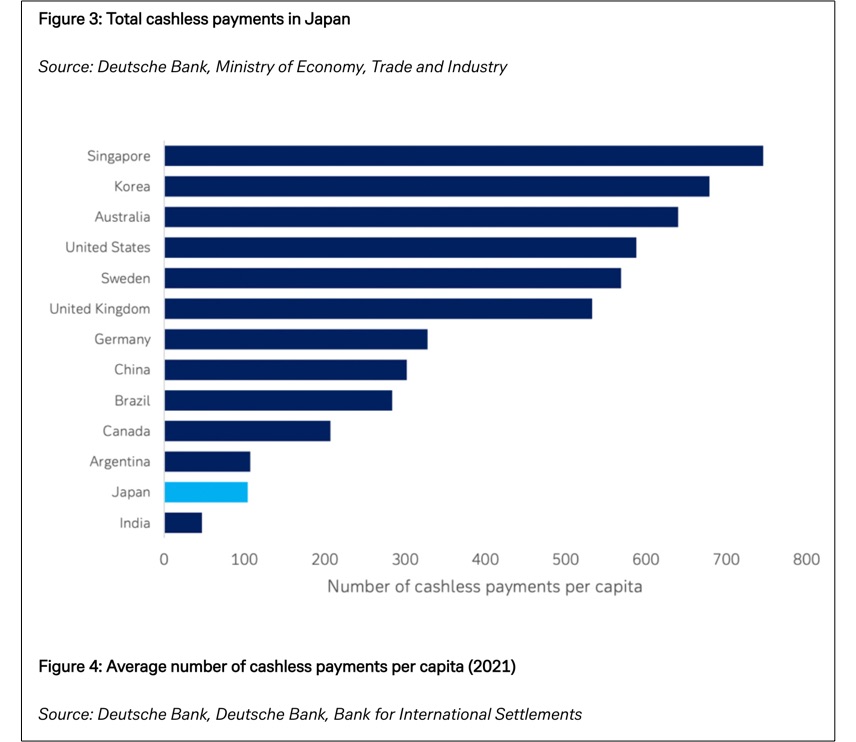

According to Deutsche Bank research, from 1995 to 2022 Japan’s circulating cash grew from less than 10% of GDP to 23%. However, like most other high income countries, the trend reversed toward a cashless economy. During the first half of 2023, cash circulation declined while coin use had been sliding for more than a year.

Covid is one reason for the cashless surge. But observers also blame piggy banks. In Japan, families are now charged for the coins they regularly deposit from children’s home savings. The result is fewer coins. In addition, like everywhere, cashless payment technology is spreading with the government and Japanese companies increasingly using digital salary payments.

Different from other high income countries, Japan likes cash:

Our Bottom Line: The Psychology of Cash

The #3 reason to use cash is that it “prevents overspending.”

At this point a scientist could remind us that the pain receptors in our brain are activated when we spend cash. Agreeing, a behavioral economist would say it’s loss aversion. Because spent money is invisible when we use plastic or our smart phones, our loss aversion diminishes. On the other hand, a smaller stash of cash can be painful.

Returning to the Himalayan hillsides where we began, new notes will soon be circulating in Japan. Shown as our featured image, the “father of Japanese capitalism,” Eiichi Shibusawa is on the 10,000 yen note ($70). They will also issue 5,000 yen and 1,000 yen notes.

And yes, this Japanese money did grow on trees (or maybe we should say shrubs).

My sources and more: Thanks to the NY Times for inspiring today’s post. The ideal complement, the cashless facts came from Deutsche Bank.