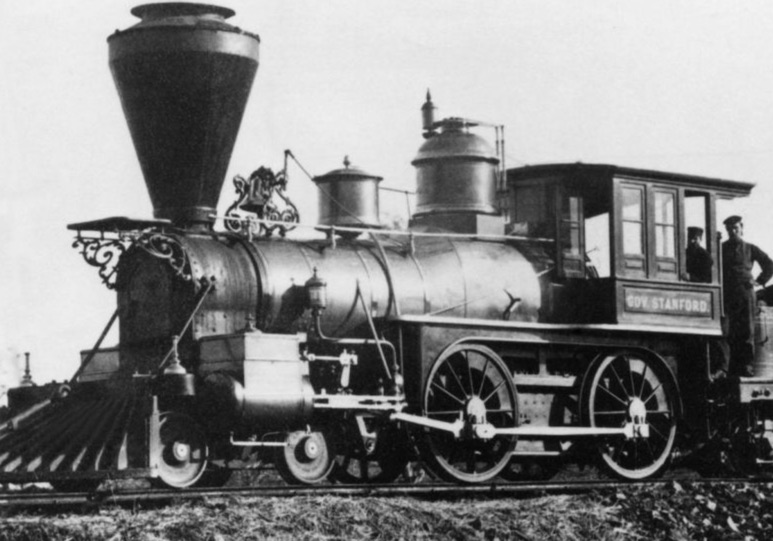

With one coming from Sacramento, California and the other from Omaha, Nebraska, two railroads met during May in 1869. At Promontory Summit, Utah, the union of the Central Pacific and Union Pacific Railroads was commemorated by a golden spike. Valued at $350, the original golden spike was 6 inches long and weighed 18 ounces. The new one is a 43-footer. It weighs 8,000 pounds and honors the Chinese and Irish workers that laid the track.

Last week, it arrived in front of the Utah state capitol:

The Golden Spike

Legend tells us that nineteenth century railroad tycoon Leland Stanford hammered the first golden spike. But actually, he didn’t. According to historian David Ambrose, Stanford missed. Instead of hitting the spike, he slammed a rail. Still though, the telegraph wire that was attached to the spike and to the sledgehammer sent the message. The wire said, “Done.”

“Done” is commemorated below:

Meanwhile, two days earlier, on May 8th, the parades had begun and the cannon had boomed in San Francisco and Sacramento. They went ahead with the celebration on its scheduled day although the spike ceremony was delayed in Promontory by late arriving dignitaries.

Celebrated on May 10, 1869, the completion of the first transcontinental railroad meant we could travel from San Francisco to New York in seven days. Before that, it could have taken months. Meanwhile, plunging from more than $1000, a first class ticket in a sleeping car was $150 and emigrant class–a bench–was $65.

Even more crucially, the railroad added to our transportation infrastructure.

Our Bottom Line: Transportation Infrastructure

We could say that our transportation infrastructure began when representatives from Maryland and Virginia met in 1785 at the Mount Vernon Conference (yes, the meeting was at George Washington’s home.) to rationalize Potomac navigation. The result was a 13-point document that proclaimed the river was a “common highway.” From there we can jump to a 19th century Clinton who lived in New York. As governor, George Clinton jumpstarted East West commerce by building the Erie Canal. Connecting Albany and Buffalo NY in 1825, it became easier and cheaper to ship manufactured goods and crops between the East Coast and the Midwest. Perhaps though, we reached its culmination with the transcontinental railroad.

The result was a national market. The Northeast could concentrate on manufacturing, the West could grow farm goods and raise livestock, the South could focus on cotton. What you did not provide locally, you could get from a distant place. Rocky New England farms no longer needed to grow tobacco. People in the South could stop making their own shoes.

Hearing about a national market, 19th century economist David Ricardo would ask us to remember comparative advantage. He would say that each part of the U.S. should produce and trade whatever requires the lower opportunity cost. By sacrificing less than other areas that need more resources to produce the same items, each region becomes more productive.

Returning to our title, we can ask about the value of a golden spike. The answer is a national market.

My sources and more: Detailing the golden spike sculpture, this article is a good starting point. From there, NPR and KSL had more. However, for the story of the transcontinental railroad, the Stephen Ambrose book is wonderful. Much briefer, Gilder Lehrman has a fact sheet.

Please note that parts of “Our Bottom Line” were in a past econlife post.