Soon after investors saw Lyft’s fourth quarter earnings press release, the company said, we made a mistake. But it was too late. Grabbing the data, auto trading bots (and other fast traders) boosted the stock price 62%.

The problem was a decimal point. Whereas investors expected a margin metric to be projected at a .5 percent increase, a misplaced decimal elevated it to 500 basis points or 5 percent. Still, because investors liked Lyft’s other numbers the stock price went up–but not as much.

You can see the pop:

Typos can be expensive.

Expensive typos

Deutsche Bank and UBS Warburg

The Lyft glitch has been called a fat finger error. At Deutsch Bank in 2015, a trader’s fat finger accidentally sent $6 billion to a hedge fund client. They got the money back the next day. UBS Warburg though was not so fortunate when its trader sold shares in an advertising company, Dentsu, for Y6 instead of Y600,000. Only after losing up to $100m were they able to cancel the order.

Citibank

Slightly like Deutsch Bank, Citibank also inadvertently sent a “check” when it accidentally repaid a loan. A bit more complicated, the story involved the cosmetics company Revlon, some hedge funds, and a loan that Citibank was administering. However, when it came time to transfer the interest payment, instead they repaid the principal. The problem here was outdated, easily misunderstood software. Although Citi assumed they were sending the interest, instead bank employees wired the $900 million principal. Happy to be repaid a chancy loan long before it matured, some hedge funds tried to keep the money. In 2022, after Revlon entered Chapter 11 bankruptcy, a U.S. Court of Appeals told the hedge funds to return $500 million to Citibank.

Samsung Securities

Five years ago, at Samsung Securities, one of South Korea’s largest brokerages, each employee received 1,000 company shares instead of each getting a 1,000 won ($.94) dividend from a company stock ownership plan. It could have cost the company 112.6 trillion won (close to $105 billion) but the shares had to be returned (and most were).

Our Bottom Line: Benford’s Law (The First-Digit Law)

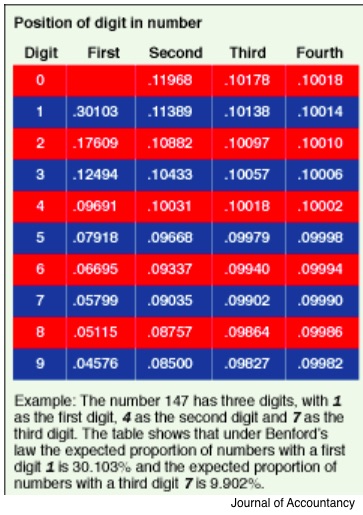

Benford’s Law is one way to know if a number is wrong. The key word is frequency. A “1” will show up much more frequently than other numbers. So, if you see a 9 as the first digit of a number, alarm bells should start to ring.

The story of Benford’s law starts at Southern Methodist University during the 1920s when Frank Benford noticed that the front pages of his logarithmic tables were more worn than the back ones. Unlike most of us, he began to wonder if there were more lower numbers in the world.

So, after going through 20,229 examples from sources that ranged from geography to demography to Reader’s Digest, he concluded he was correct. Whereas 1 was the first digit in 31% of his numbers, 9 was the first digit in just 5%.

Below, you can see Benford’s Law (a.k.a. the first-digit law). For the number 876, there would be just a 5.1% chance that 8 would have been your first digit. Do take a look at the likelihood of a 7 for a second digit and a 6 for the third:

Benford’s Law could also alert us to a possible typo.

My sources and more: Described in a slew of articles, the Lyft mistake became real in this Washington Post article. Then, for other typos, WSJ, here and here, FT, The Economic Times, and Vanity Fair were ideal. Meanwhile, if you move onward to just one more article, do look at the Benford story.

Please note that several sections from today were in a previous econlife post.