Last week, we shared two Daniel Kahneman stories.

But there is much more that he said about investing.

Daniel Kahneman’s Investing Insight

As the only psychologist to win the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, Daniel Kahneman (March 5, 1934-March 27, 2024) had lots to say about how we invest.

Two Decision-Making Modes

Dr. Kahneman starts Thinking Fast and Slow with our two basic decision-making mechanisms. Reacting with System 1 or System 2, we either think fast or we think slow.

System 1 is our intuitive, fast, initial reaction. Faced with a situation, we immediately respond with minimal (or no) contemplation. Our emotions and intellect are automatic. We hear a loud noise and prepare to run. We see 96 x 34 and know it is multiplication. Or, as investors, we observe everyone (reputedly) making money and quickly say, “Buy, buy, buy.”

By contrast, System 2 is our slower thinking mode. When we employ System 2, we devote effort to assessing and deciding. Using System 2, we might try to figure out the source of a loud noise and the answer to 96 x 34. And, as investors, we could look for a company’s history, its PE ratio, its profit margins.

You can see why System 1’s path is different from where System 2 takes us:

Dr. Kahneman might have warned us about investing decisions that are based on System 1.

Loss Aversion

From there, he could have continued with people’s 80/20 response. Asked if you would proceed with an investment that had an 80 percent chance of success, the replies tilted to yes. But then, when asked if they would chance losing 20 percent, investors refused. Although both were the same, System 1 dislikes losses much more than it enjoys gains.

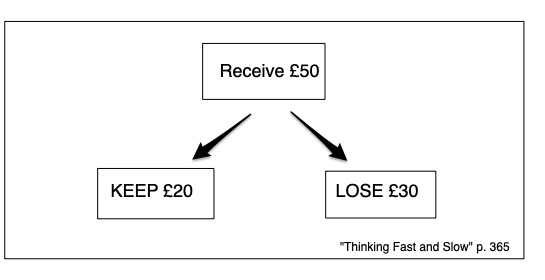

Somewhat similarly, the Kahneman insight for another illogical pair of decisions took him to a System 1 preference that related to how a decision is framed. Here, people preferred keeping £20 rather than losing £30 when they had £50. Explaining, he said their System 1 directed them to the word “keep” as the “sure thing” although losing £30 was the same thing.

Sunk Cost

Next, at this point, he certainly would have cited the sunk-cost fallacy. My own example of sunk cost always is about phone waits. After I’ve been placed “on hold” for 20 minutes, do I continue? Many of us look back at our “sunk” 20-minute cost and think we will stay. Instead, though, we should look ahead at the costs and benefits of remaining on the phone for the next 20 minutes or so. Of course, with investing, a System 1 and System 2 response to sunk costs will be very different.

Our Bottom Line: Framing

Then, to all of this, we can add broad framing. For investors, that means resisting the urge to check stock prices every day or even weekly. The broad frame could even be a quarterly peek because, as Dr. Kahneman said, “The combination of loss aversion and narrow framing is a costly curse.”

And finally, concluding, he told WSJ’s Jason Zweig that, “All of us would be better investors if we just made fewer decisions.”

My sources and more: Thanks to WSJ‘s Jason Zweig for inspiring today’s post on Daniel Kahneman’s investing insight. From there, I returned to Thinking Fast and Slow for Dr. Kahneman’s “advice” and then discovered this Pimco look at behavioral economics.