In London during the early 19th century, store clerks who knew what was high, what was low, and what would generate a profit were prepared to haggle. Time consuming, the process meant every customer could have a different price.

But then we had the invention of the 19th century department store. Think New York’s Macy’s. It would have been impossible and impractical to train hundreds of employees to negotiate a price for thousands of items. The result? The price tag.

With single prices, customer service could blossom as would customer loyalty. We could also have price wars, money-back guarantees, loss leaders, and promotional pricing, Auto dealers tell us that fixed prices for cars cuts buying time by 82 percent from more than four hours to 45 minutes. The same change transformed the retail experience so compellingly that by 1890, one price for each item had become the norm.

Now though, sort of back to where we started, we again have different prices for the same item…even hamburgers.

Dynamic Pricing

The firms that use dynamic pricing change the price of the item they sell during an hour, a day, or a month. Typically using supply and demand data, they select the price that will optimize profits at that moment.

Wendy’s

During its investor conference call several weeks ago, Wendy’s CEO told us that its digital menu boards will have different prices during the day.

The uproar followed.

Assuming that Wendy’s was following Uber’s surge model, the media thought Wendy’s CEO meant that when demand went up, so too would prices. The company quickly responded that its dynamic pricing was a discounting model used to lower prices.

Coca-Cola

During the 1990s, Coca-Cola said that its vending machine prices would respond to demand and temperature. When the weather was hot and people got thirstier, prices would rise. Saying Coke was exploiting its customers, Pepsi loved the decision. Coke quickly changed its mind.

Airlines

Perhaps though, it’s the airline industry with which we most associate dynamic pricing. There, it all began in 1978 with deregulation. At the time, one Delta executive became horrified that his reservations staff had lowered fares for the Atlanta/Washington D.C. route as the departure date approached.

I suspect I would have lowered those fares also. If you have empty seats, it makes sense to attract more fliers by lowering the price.

The right approach though was precisely the opposite. Knowing that last minute fliers are willing to pay much more, the airline should have been increasing fares. Quickly moving to a dynamic pricing model from one controlled by government, the airlines decided fliers on the same plane could pay different fares. It all depended on whether the flier was discretionary or business, if the flight was departing in days or months, and how many seats remained.

Amazon

While Amazon too is a dynamic pricer, the time frame varies. The changes could be hourly, moment to moment, monthly. A NY Times journalist tells us that Amazon increases and decreases prices millions of times a day. Citing the Pokémon Celebrations Elite Trainer Box, price “seesawed” from $49.99 to $89.99 between August and December.

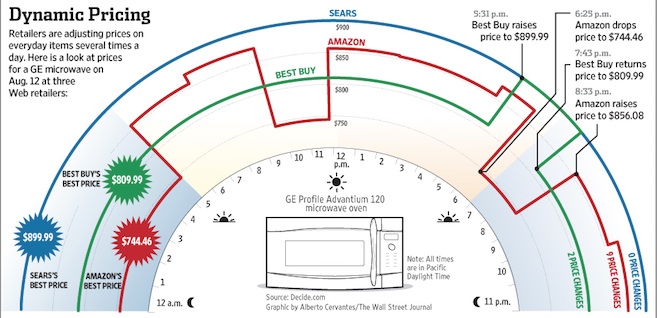

While this WSJ graphic of price fluctuations for a GE microwave is for August 12, 2012, recent articles indicate the phenomenon remains accurate.

Our Bottom Line: Pricing Power

Online, we have airlines and Amazon raising and lowering prices. In addition, using an approach like Wendy’s, brick and mortar stores have experimented with the Electronic Shelf Labels that also vary prices,

In traditional economic texts, we say that pricing power increases as we move to the right along a competitive market structures continuum. Moving from perfect competition to monopolistic competition, to oligopoly and monopoly, we have increasingly powerful firms. Theoretically, the ones that are more powerful have more control over what they charge instead of the market.

As always, it is not quite that simple. Whereas farmers in perfectly competitive markets are price takers because the market dictates what they charge, in monopolistic competition, firms have some power. Here though is where Amazon’s dynamic pricing could kick in and supercharge their power. By contrast, as an oligopoly with considerable price making power, Apple does not engage in dynamic pricing. I am pretty sure that it has kept its price tags.

As a result, asking about missing price tags, our answers are messy. Why might a monopolistically competitive firm not have one while a perfectly competitive firm and Apple do?

My sources and more: To start, the NY Times had the story of Wendy’s dynamic pricing decision (and more) and it also detailed Amazon’s dynamic pricing strategies. Meanwhile the Amazon details were at CBS and here, and at econlife,

Please note that several of today’s sentences were in a past econlife post.