Like humans, bananas have their temperature taken to be sure they are healthy.

Let’s take a look at why and much more.

A Banana’s Travels

The Past

Our story starts in Jersey City where the first U.S. bananas arrived in 1870. Called the Gros Michel, these banana ancestors didn’t ripen too quickly nor bruise too easily and were reputedly super tasty.

We could have found the Gros Michel at Wall Street’s Banana Docks:

You and I, though, were not destined to enjoy them. By 1960 very little remained of the Gros Michel because of a fungal disease that had been spreading for 40 years. The one replacement possibility was a second rate banana called the Cavendish. Its taste was somewhat bland, and it needed pesticides and ethylene ripening.

You and I, though, were not destined to enjoy them. By 1960 very little remained of the Gros Michel because of a fungal disease that had been spreading for 40 years. The one replacement possibility was a second rate banana called the Cavendish. Its taste was somewhat bland, and it needed pesticides and ethylene ripening.

But the Cavendish survived the fungus.

The Present

So yes, the banana on your kitchen counter is probably a Cavendish. Based on this ripening chart, it could be a #6. But, arriving in the U.S., it was a #1:

Typically grown, harvested, and packed in Costa Rica, a Dole banana might start its U.S. journey at the port of Wilmington in Delaware and then travel to a ripening facility in the Bronx, NY. After a temperature check confirming that the banana is close to 56 degrees, huge containers of boxes of bananas get the ethylene gas that brings them to somewhere between a ripeness of 2.5 to 4 with a color that is 75 percent yellow and 25 percent green.

Do take a look at how our bananas get ripe:

The Future

Because Cavendish bananas are genetically identical, anything that kills one can kill them all…

Like Tropical Race 4.

In the following map, the dots identify where to find Tropical Race 4. However, one dot is missing. During April, Peru reported its first case:

You can see that Ecuador, the world’s largest banana exporter, is located between Peru and Colombia, the two South American countries where where Trace 4 has been sited:

Our Bottom Line: Supply Chain

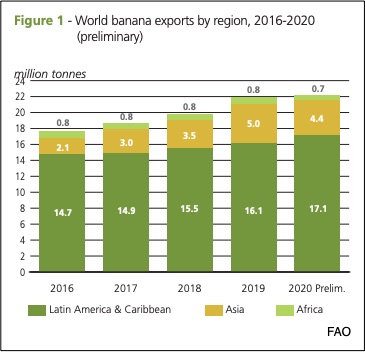

Looking at a banana’s travels, we’ve really just focused on some links in a supply chain that starts with its exporters:

And winds up with most being imported by the EU and U.S.:

So massive a supply chain gives us a clue as to why growers have not replaced the Cavendish. An economist would say that it is all about opportunity cost. At this moment, switching creates too great a sacrifice.

Sources and Resources: Excellent for banana history and production, this NY Times Op-Ed from Dan Koeppel, this Freakonomics post and this New Yorker article and video provided all you would probably want to know about banana economics. Then, for a more recent update, the FAO, the Packer, and the Eater video have the facts while Atlas Obsura found samples of the Gros Michel.

Our featured image of the Gros Michel was from Atlas Obsura. Also please note that today I’ve included parts of previous econlife posts.