The U.S. dollar is a handy backup when a country’s currency loses its value. After Zimbabwe’s hyperinflation hit its peak (or its nadir) in 2009, they used U.S. dollars but didn’t have enough. So, when the cash got too gray and dirty, they washed it.

You can see the dollar entering a washing machine in this 2012 photo:

I wonder if Venezuela might wind up with the same problem.

Venezuela’s Hyperinflation

Making a long story very short, we can start with Venezuela’s oil boom during the 1970s, a 1980s glut, and an IMF bailout. Next, fast forwarding to 1998, Hugo Chavez brought his version of socialism to Venezuela. Using the country’s immense oil wealth, he subsidized necessities and reduced poverty.

The problem though was that it all depended on the price of oil. And when it sunk, the Venezuelan economy tanked because Chavez had distorted all market activity through price controls and expropriation. He took over land and businesses and attacked entrepreneurs. Yes, those with less got more. But also, lines outside supermarkets got longer as shortages multiplied. By 2007, price and capital controls had begun to create economic havoc. Standing in line for hours, people hoped to get some cheap cooking oil, milk, bread, and pork before the store ran out.

By 2013, after Hugo Chavez died and Nicolas Maduro continued his policies, all got worse. Shortages became so severe that in 2017, the average person was said to have lost 24 pounds. In 2018, the monthly minimum wage went up 60-fold to 1800 bolivars while the currency was devalued by 96 percent. For the year, inflation was 80,000 percent.

In 2018, this 2.4 kg chicken cost approximately 14.600,000 bolivars (USD $2.22 or £1.74):

These carrots were 3,000,000 bolivars:

But things could be getting better.

Because President Maduro eased import and dollar restrictions, some economic life is sprouting. Small bodegas that sell milk and pancake mix or even Nutella are popping up in beauty salons, car repair shops, in small stores. Buyable only with dollars or U.S. bank cards, the commodities are coming from Florida. Relatives, friends, entrepreneurs, are buying items at Costco and then sending them for resale in Venezuela. It’s been estimated that $2.7 billion US dollars are now circulating in Venezuela.

Our Bottom Line: Hyperinflation

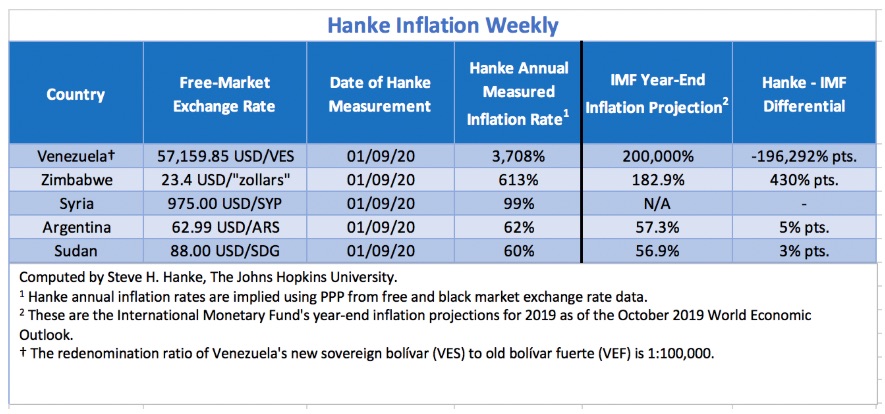

Johns Hopkins Professor Steve Hanke tells us that Venezuela’s recent inflation rate is 3,708 percent:

To understand Venezuela’s hyperinflation, he suggests that we think of PPP (purchasing power parity). PPP shows how much two currencies can buy of the same item. It lets us compare purchasing power. Assume for example that a loaf of bread is 50,000 bolivars in October, 100,000 in November, and 200,000 in December. We just need to know that each of those bolivar prices could be converted to the same (hypothetical) dollar amount–maybe $1. You can see that you need lots more bolivars but the same dollar for your loaf of bread.

And do remember 50 percent. If, during 30 consecutive days, prices rise by more than 50%, you have hyperinflation. Furthermore, when the increase stops for a month or two and then begins again (within a year), you are in the midst of the same hyperinflation.

So where are we?

You cannot tether an out-of-control currency. Venezuela has tried raising the minimum wage, printing more money, and price controls–all to control the upward march of prices. None of it worked. The alternative is dump and replace. You dump your currency and replace it with the dollar.

And then you might have to launder it.

My sources and more: You can always check Steve Hanke’s calculations at the CATO Institute. Then, for Venezuela’s hyperinflation, there are countless possibilities. Reuters described the 2018 currency and wage gyrations. The Council on Foreign Relations has a handy timeline while Forbes told us a bit more. Also, for a bit of Zimbabwean history, WSJ, was helpful. But if you just want a good listen and the source of my recent facts, The Indicator podcast is ideal.

Please note that several parts of today’s post were in a previous econlife and our images of Zimbabwean money laundering are from WSJ.