On Tuesday, September 12, the trial began.

In U.S. and Plaintiff States v. Google LLC, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) will try to prove that Google violates Section 2 of the Sherman Antitrust Act. Unimaginable to the writers of this 1890 Act that was supposed to maintain competition by preventing large entities from “restraining trade,” Google is charged with monopolizing internet search activity. More precisely, its search services and search advertising allegedly give Google control over search markets.

The Timeline

First filed in 2020 by the DOJ, 11 states, and three that joined soon after, the Google antitrust case began. Now, having added an (almost) identical suit from 35 states with Guam, Puerto Rico and the District of Columbia, the court will hear from a gargantuan group of plaintiffs. Two years ago, during the “Discovery” phase of the case, the plaintiffs and Google exchanged the information, including witnesses and documents, that they could present at the trial. Typical in a case like this, Google asked for a summary judgment that would skip a trial and rule in its favor. Meanwhile, by June 2023, the parties exchanged initial trial information that included witnesses and exhibit lists and, after September 1, they had their pre-trial conferences. With no summary judgment having been granted, the trial began on Tuesday.

The Google Antitrust Lawsuit

Because of “exclusionary agreements,” that make Google the default search engine, the DOJ says 90 percent of all search queries go to Google. On Apple devices, Safari uses Google for search. Similarly guaranteeing their use, with Android devices, Google Apps are pre-installed. At the same time, the DOJ asserts that Google overcharges advertisers and impedes the innovation and search engine choice that would benefit consumers.

Responding, Google said it competes with other search engine for its default status. They also point out that users can switch search engines. But perhaps, most crucially, they say that their service is the best. As a result, consumers overwhelmingly choose them.

It all sounds a little like Standard Oil and Microsoft.

Standard Oil and Microsoft

Standard Oil

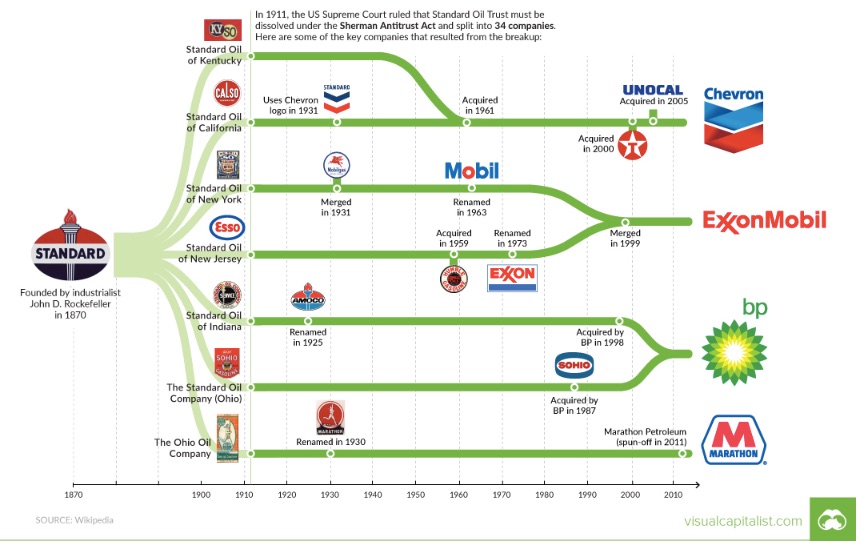

On May 15, 1911, the Supreme Court divided a gargantuan oil trust into 34 smaller companies that actually were very large businesses. They included Standard Oil of New Jersey, Standard Oil of New York, Standard Oil of California, Standard Oil of Ohio, and Standard Oil of Indiana. Now we know some of them as Chevron, ExxonMobil, and Marathon:

The Supreme Court explained that Standard Oil was violating the 1890 Sherman Antitrust Act by acting “in restraint of trade.” In the NY Times, the story was huge:

Below, Standard Oil’s founder, John D. Rockefeller, is approximately 60 years old. With a net worth of $27 million in 1887, $324 million in 1913, and close to $1 billion at its height, John D. Rockefeller died when he was 97 years old in 1937:

Standard Oil began with what we now would call some venture capital. A Mr. Andrews approached John D. for money to build an oil refinery. While at first Rockefeller and his partner contributed $5,000, soon John D. left his produce business, bought out his partner, and devoted himself exclusively to oil. He accurately saw that the demand for oil would skyrocket. At first one of thirty, he soon became the largest oil refiner in the Cleveland area, owning a network of warehouses and tank cars, and displaying a talent for giving railroads rebates and (initially) undercharging customers. By 1870 he had incorporated as the Standard Oil Company of Ohio, destined soon to quash all competition and control the entire industry.

Microsoft

Fast forwarding to 2001, we have U.S. v. Microsoft. Like Google, Microsoft was charged with default agreements. Vastly simplifying the case, we can just say that, on your computer when you purchased it, their browser and Windows operating system were pre-installed. As a result, switching to competitors was a hassle for consumers. Judging their behavior as a Sherman Act violation, the Court ordered a Microsoft breakup. Instead, having negotiated a settlement through which PC manufacturers could adopt non-Microsoft software, Microsoft remained whole.

Our Bottom Line: Competitive Market Structures

As economists, we could say that the DOJ’s antitrust concerns relate to where we place Google on a competitive market continuum. The farther right we move, the less competitive we get. A perfectly competitive market structure has many small firms that make almost identical products and sell to thousands of customers. The firm has almost no power. Its price and costs are dictated by the market. However, as we move to the right along the scale, companies get increasingly powerful until we reach the far right. Because there, firms with monopoly power can determine price and swamp competition, the Sherman Act kicks in. Here though we are looking at the new kind of power from tech. Rather than price abuse, it takes us instead to data control.

The court will tell us where to place Google on our competitive market structure graphic. Its position will tell us if Google is harming you:

My sources and more: Combined, this timeline, the Harvard Law School summary, and the story of the first day in court, said most of what we need to know about the DOJ v. Google. As for Standard Oil, I went back to my book, Econ 101 1/2 (then Avon books–now Harper Collins)

the assimilation of Chicago-school Borkianism into the judicial system has resulted in the majority of essential industries being dominated by a small handful of giant corporations. The resulting economic (and consequent political) power has, via monopsomies in labor and wholesale purchasing, impoverished large sections of the populace; and consumers (initially benefitting from efficiency, according to Bork) are now seeing the ultimate “enshittification”.

Adam Smith himself clearly stated the dangers of collusion among suppliers. But “wink and nod” collusion is not exclusively a function of human nature. Profit maximizing AIs would do exactly the same thing. And if you think that simple logical tautologies don’t also contribute to gini, then you need to review the chapter on random walk with absorbing walls in your undergrad probability text.

In a free capitalist society, it is vital for government to put a thumb on the negotiating scales, in favor of the powerless.