The NY Times tells us that climatarian is “so 2022.”

Instead, now we are regenivores.

Our Food’s Carbon Footprint

Whereas a climatarian preserves what is by eating sustainably, regenivores look for carbon reducing policies that create what could be. The common thread though is what they expect from the corporate world.

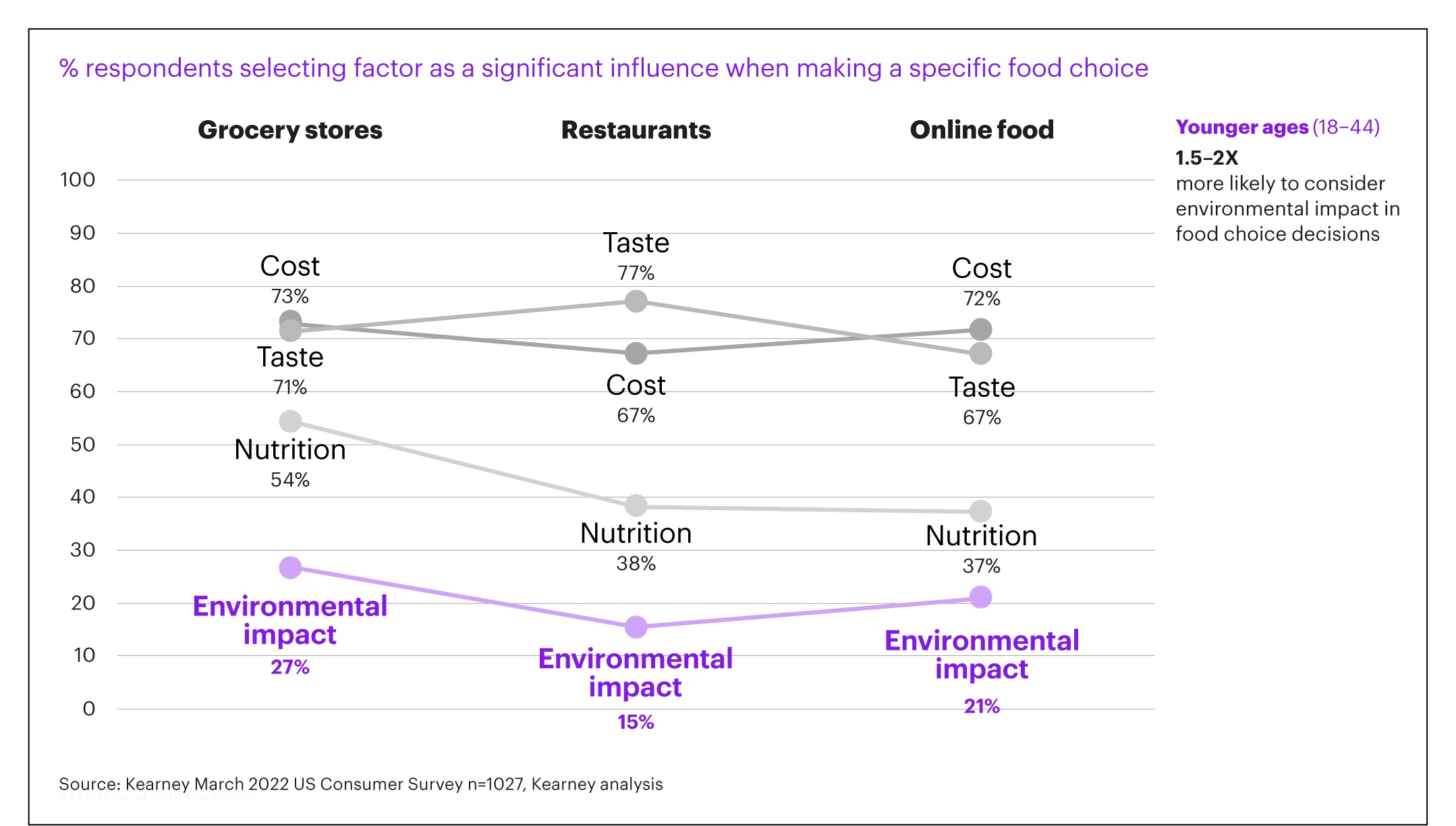

In a March 2022 study, 1027 participants said they were more likely to care about their food’s carbon footprint in a supermarket:

Supermarkets

Selecting milk, in 2009, Tesco became the first major supermarket chain to display a carbon footprint. Their goal, they said, was to help customers grasp climate change with 500 labels by the year’s end. During 2012, though, they ditched the initiative. Their reason was the complexity and that no others had followed their lead. They said it would take centuries to label all of their 70,000 products. Now, a decade later, still supermarket carbon footprint food labels are sparse. The one example I could find was the Danish cooperative chain, Coop.

Restaurants

By contrast, green labeling at restaurants seems to have become more palatable. With large chains like Just Salad, Panera Bread, and Chipotle adding the labels, we might have a movement that is gathering momentum in their monopolistically competitive market.

At Chipotle, you can check if your lunch had a reduced carbon foodprint.

Our Bottom Line: Carbon Footprint Standardization

The people that calculate the environmental impact of a product might have measured the water given to livestock, the fertilizer that was or was not sprayed, the refrigeration during transport. They could have included the consumer’s impact. Or maybe not.

And that is the problem.

In 18th century France, you can see why all of us need standardization. The size of a pint could have varied by 20% between villages. And that was just one metric. Imagine dealing with many when buying and selling merchandise. It helped the market considerably when two scientists defined the size of a meter during the 1790s by calculating the distance from the North Pole to the Equator and dividing it by 10 million. Once they knew the size of a meter, they said the kilogram was “a cubic decimeter of rainwater at 4 degrees Celsius.” One result was a platinum kilogram cylinder. But the bigger impact was the standardization of a wide array of weights and measures. Traveling from one city to the next, you knew the length of a meter.

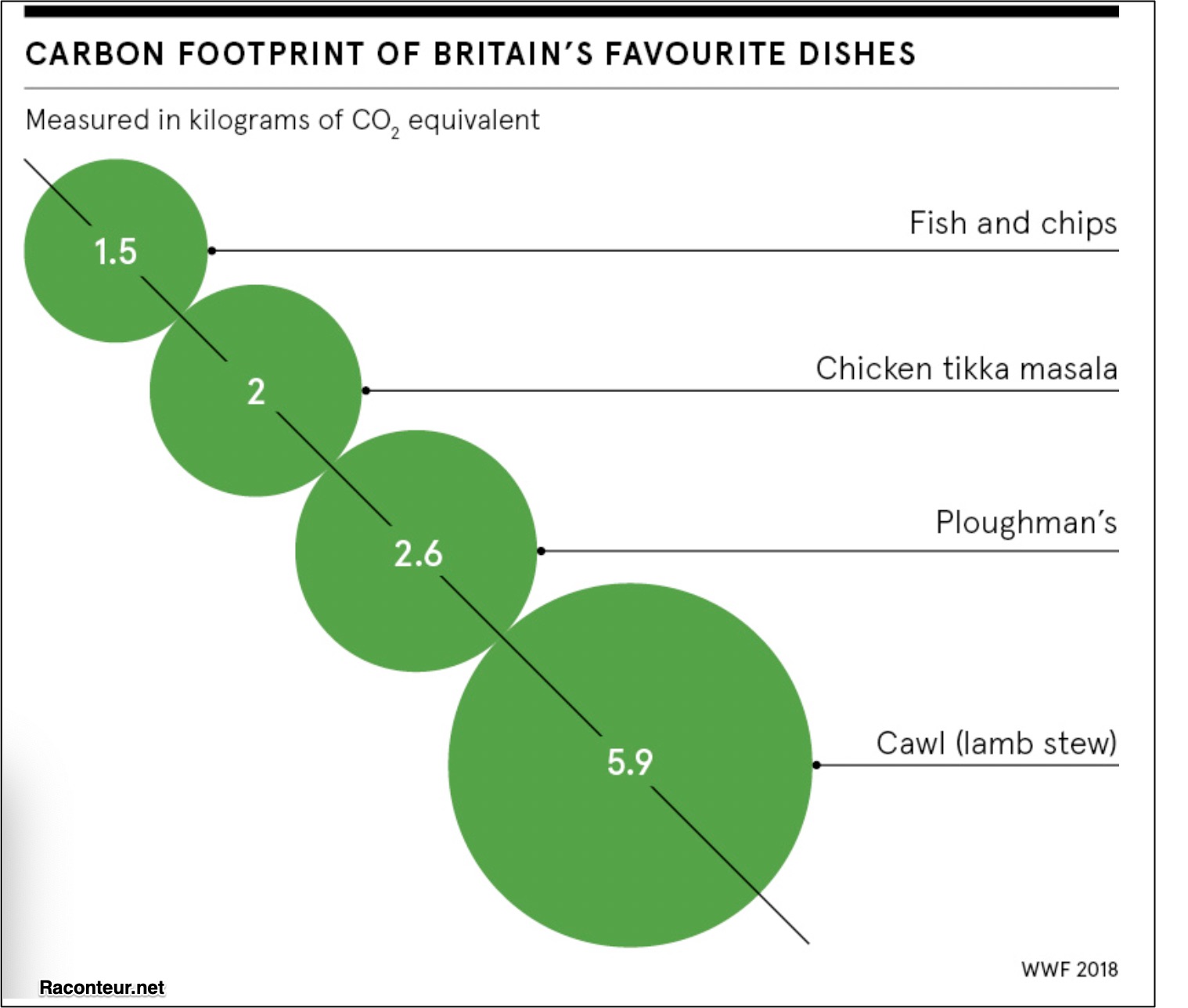

Looking at the carbon footprint of some of Britain’s favorite foods, we do not know if their production and transport were similar. And maybe you, like I, do not know what a 1.5kg equivalent means:

Yes, taking some strides forward, the SEC has proposed rules for standardized ESG reporting. But all of it reminds me of Mandelbrot’s British coastline. The closer you look, the more infinite its length.

My sources and more: Thanks to yesterday’s Bryan Lehrer Show for alerting me to the climatarian phenomenon. From there, Jennifer Kingston’s climatarian article had more detail with links to the NY Times and Kearney consulting. Meanhile, a Just Salad sustainability link was helpful for a firsthand picture of a corporate initiative as were narratives about the Tesco label saga, here and here. Please note that most of “Our Bottom Line” paragraph on standardization history was in a previous econlife post.