Given the following list of reasons for hiring a dog walker, which ones do you think occupy the top three slots?

- Family responsibilities

- Difficulties with dog

- Bad weather

- Work

- Laziness

Like me, you might have put work at the top. We are wrong. According to a Psychology Today survey, it’s bad weather (56%), then laziness (32%), then work (32%), with dog difficulties (31%) and family (24%) at the bottom.

Dog Walking Economics

In the U.S., four out of 10 dog owners don’t walk their pets regularly. Satisfying their demand, there are approximately 29,000 dog walking enterprises that employ an estimated 51,000 walkers. Because it is easy to enter and exit the “industry,” the numbers are in flux. After all, you just need several leashes, lots of doggie bags, and some Kibbles.

Called names like Wag and Fetch, dog walking businesses have grown as more entrepreneurial walkers hire assistants. Perhaps must crucially, though, they have figured out their own economies of scale whereby output multiplies. Orchestrating groups, they do have to cope with the random squirrel that simultaneously stimulates six creatures. And also, when shy and aggressive dogs are together, their interaction can be catastrophic.

But still, the dollars make sense. Below you can see how monthly income ascends to as much as $12,000 when you walk groups of six, five times during each day:

The Pandemic Impact

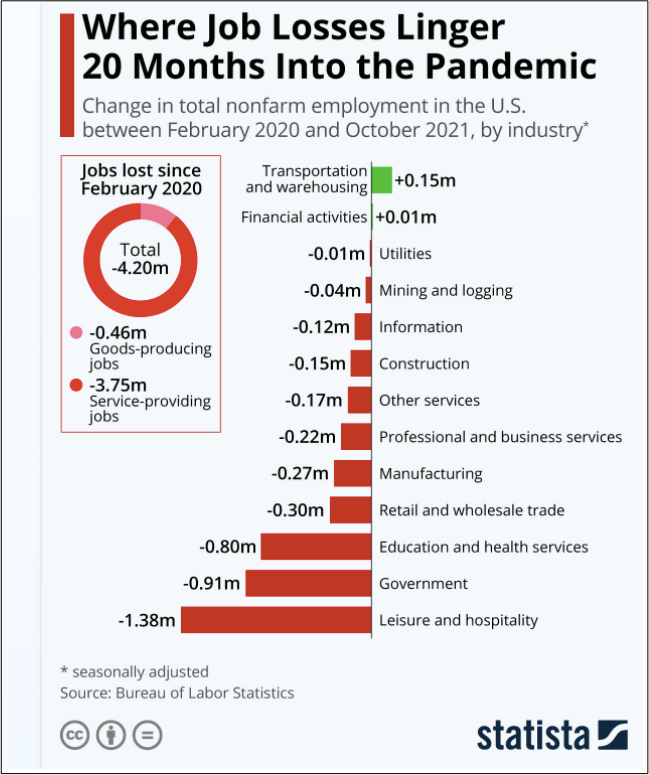

While service industries have disproportionally suffered during the pandemic, The Washington Post told us in August, 2020 that private breeders and nonprofit rescues saw applications soar. Explaining, they say that people craved company. Ranging from loneliness to keeping children busy, canine ownership solved some Covid problems. Although I doubt that anyone has dog walking stats, it makes sense that they have not the experienced the service sector job losses illustrated below:

Our Bottom Line: Adam Smith

We could say that economic thinker Adam Smith provided order to a seemingly chaotic 18th century marketplace. A quick glance revealed countless businesses selling goods and services to an equally large number of consumers. Why and how all were reasonably satisfied was somewhat mystifying. We like to say that Smith’s answer was the invisible hand. Although he referred to the invisible hand only once in his 1776 masterpiece The Wealth if Nations (and 2 more times in other books), the idea stuck.

Because of a nudge from the invisible hand, profit seeking individuals start businesses. To optimize sales, they produce what buyers need and want. If prices are high, then, charging less, competitors enter the market. As the market grows, productive capability increases through a division of labor whereby workers each do a different task. At the same time, the invisible hand is nudging consumers to satisfy their needs.

In today’s title, we asked where dog waking takes us. It takes us to the market.

My sources and more: Again my source of an interesting idea, The Hustle alerted me to dog walking economics. The ideal complement, this Washington Post article focused on the demand for dogs Meanwhile, taking the leap to Adam Smith, this article provides insights about his view of the invisible hand. Our featured image is from Amanda Andrade-Rhoades for The Washington Post.