Two recent events might be accelerating Amazon’s antitrust concerns.

Last Tuesday, Lina Khan became the new chair of the Federal Trade Commission. Four years ago, Lina Khan wrote a Yale Law Journal article, “Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox,” that went viral with 146,255 hits. Then, also during this month, five bills were introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives. While their overall goal is to limit the power of “Big Tech,” if passed, they could require an Amazon breakup.

It all sounds a little like Standard Oil…but maybe not.

The Standard Oil Antitrust Case

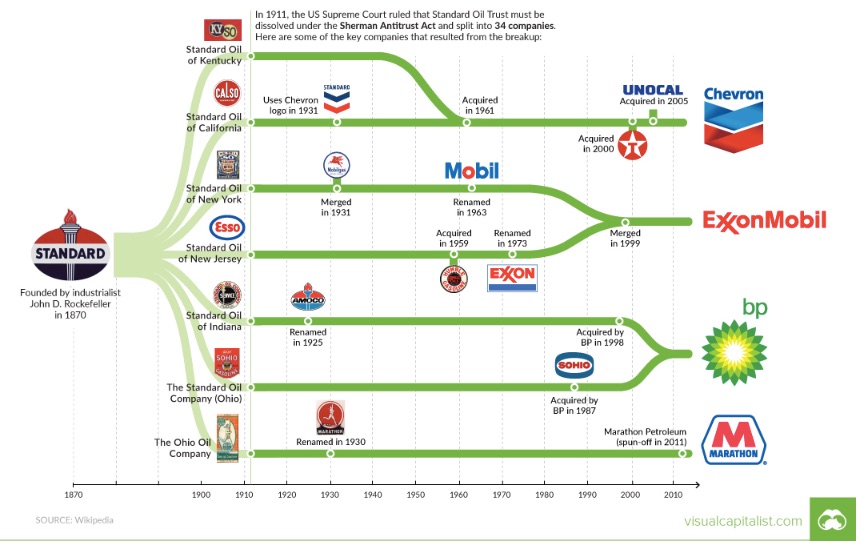

On May 15, 1911, the Supreme Court divided a gargantuan oil trust into 34 smaller companies that actually were very large businesses. They included Standard Oil of New Jersey, Standard Oil of New York, Standard Oil of California, Standard Oil of Ohio, and Standard Oil of Indiana. Now we know some of them as Chevron, ExxonMobil, and Marathon:

The Supreme Court explained that Standard Oil was violating the 1890 Sherman Antitrust Act by acting “in restraint of trade.” In the NY Times, the story was huge:

Standard Oil’s Founder

With a net worth of $27 million in 1887, $324 million in 1913, and close to $1 billion at its height, John D. Rockefeller died when he was 97 years old in 1937.

Below, John D. Rockefeller is approximately 60 years old. The artist was Oscar White.

His story begins with some rather unorthodox child-rearing practices. John D.’s father reputed said, “I cheat my boys every chance I get, I want to make ’em sharp .. .” Meanwhile, his mother, a determined disciplinarian who felt bound to “uphold the standard of the family,” continued a thrashing even when she concluded that John was innocent, saying, “Never mind, we have started in on this whipping and it will do for the next time.”

Considerable discipline, minimal schooling, and hard work for nearby farmers seem to characterize Rockefeller’s childhood in western New York and then in Cleveland. Although a day of hoeing potatoes brought him only thirty-seven cents, he soon accumulated $50, which he is said to have loaned to the farmer for whom he worked. Commenting on his early business ventures, he said, “I soon learned that I could get as much interest for $50 loaned at seven percent… as I could earn by digging potatoes for ten days.”

As a high school student, the study of bookkeeping “delighted” him and led to his first position at sixteen as a bookkeeper with a local merchant. Accumulating $800 in savings in only three years (having earned $15 a month at first and later $50), he soon became a merchant himself.

Standard Oil’s History

Standard Oil began with what we now would call some venture capital. A Mr. Andrews approached John D. for money to build an oil refinery. While at first Rockefeller and his partner contributed $5,000, soon John D. left his produce business, bought out his partner, and devoted himself exclusively to oil. He accurately saw that the demand for oil would skyrocket. At first one of thirty, he soon became the largest oil refiner in the Cleveland area, owning a network of warehouses and tank cars, and displaying a penchant for bargaining with railroads for rebates that gave him a price advantage above all others. By 1870 he had incorporated as the Standard Oil Company of Ohio, destined soon to quash all competition and control the entire industry.

One source of Mr. Rockefeller’s success was his vertical integration. Vertical integration works like a ladder. As a vertically integrated firm, Standard Oil controlled virtually every step of the productive process. It had the wells (the first rung), the pipelines (a second rung), the barrel makers, the refineries, and the retail outlets (the top of the ladder).

So yes, Rockefeller was an extraordinary businessman. But also, he made secret deals with railroads where his rates seemed equal to everyone else’s. Actually, the railroads were giving him secret rebates and also paying him when they did business with other oil companies. Competitors seemed eager for him to buy them out. But really, he threatened to lower his prices until he put them out of business if they refused.

When we combine his acumen with his tactics, we wind up with a gargantuan business called a trust. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Trust dominated most of the industries in which it competed. For oil production, it could claim more than 90% control.

I should add here that Brookings scholar Robert Crandall believes that the Standard Oil break up was unnecessary. In an Op-Ed published 21 years ago (that was actually against splitting Microsoft), he said the market was already providing a Standard Oil solution. With the industry expanding to Texas, Oklahoma, Louisiana, Kansas, and California, the price of petroleum was falling. The new fields made the difference–not a Supreme Court antitrust decision.

His focus though was price. Now it is not.

Amazon’s Antitrust Concerns

On the surface Amazon is very different from Standard Oil. Through low prices, fast shipping, great movies, one click ordering (you know it all), it enhances consumer welfare. So why Amazon’s antitrust concerns?

Let’s look at it this way.

According to FTC Chair Lina Khan’s Yale Law Journal paper, Amazon is the platform that sells more than 120 of own products and countless others. For those Amazon products, it competes against the firms that use its platform. Reflecting its conflict of interest, Amazon owns the platform that sells its private label, has competitors selling the same items, and then also decides search rankings. Firms flock to Amazon because platforms reduce their cost of entry.

Then, as Lina Khan detailed four years ago, Amazon is a retailer and a marketing platform. It delivers packages through a logistics network, it is a payment service, a credit lender, a book publisher. It produces TV shows and films, manufactures hardware, and is a leading host of cloud server space.

Khan suggests that more recent definitions of anti-competitive behavior need updating. Although Amazon ostensibly augments consumer welfare, its behavior could be considered anti-competitive. Her concern focuses on its conflicts of interest. She cites the power that interconnected distinct lines of business create. And finally, she asks if the “structure of the market incentivizes and permits predatory conduct.”

Our Bottom Line: Competitive Market Structures

As economists, we could say that Amazon’s antitrust concerns relate to where we place Amazon on a competitive market continuum. The farther right we move, the less competitive we get. A perfectly competitive market structure has many small firms that make almost identical products and sell to thousand of customers. The firm has almost no power. Its price and costs are dictated by the market. However, as we move to the right along the scale, companies get increasingly powerful until we reach the far right. Because there, firms with monopoly power can determine price and swamp competition, the Sherman Act kicks in. But according to Lina Khan it relates somewhat differently from the past. Here, calling it “Hipster Antitrust,” we are looking at the new kind of power from tech that actually lowers prices rather than elevating them. It takes us instead to data control.

On the market structure scale, U.S. regulatory decision makers have to decide where Amazon belongs:

So, not only is the Congress, the FTC, and perhaps the courts, making a decision about the present, like Standard Oil, they are also predicting where Amazon’s markets will go in the future. But the two are very different.

My sources and more: Reading about Amazon’s antitrust concerns, I went back to the Standard Oil story from my book, Econ 101 1/2 (then Avon books–now Harper Collins), to a Brookings addition, and to a past econlife post. Then this week, it all came together in this Journal podcast and the FTC Khan appointment. Both echoed her Yale Law Journal article and this NY Times article. And, if you still would enjoy more, do go to one of my favorites, Slate Money.