Saying one pitch is a strike and another a ball, an umpire can call two identical pitches differently. Somewhat similarly, judges have given different evaluations to the same wine during a competitive tasting.

Nobel economics laureate Daniel Kahneman says the reason is noise. Let’s take a look.

Noisy Decisions

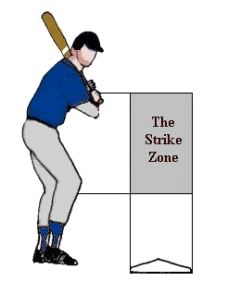

Baseball

Our story starts in Chicago. It’s a Thursday evening during April in 2010 and the White Sox are playing the Cleveland Indians. With Chicago ahead 3-2, the count is one ball, two strikes for the Cleveland batter. The pitch is probably in the strike zone–the ump has called similar pitches strikes 80% of the time. But he called it a ball and perhaps changed the result of the game. Two pitches later, scoring a runner who was on first, the batter hits a double. The game continues to the 11th inning when Cleveland wins, 5-3.

Using data from 3.5 million pitches, researchers have hypothesized that home plate umpires are less likely to call a strike (when the batter does not swing) if the previous pitch was also a strike. And they are even less likely if the previous two pitches were strikes.

Wine

Our next story takes us to the California State Fair Commercial wine competition. Judging wine involves taste and aroma, the palette and the nose. Although it is subjective, the anomalies stand out. Wines that get gold medals in one competition fail to place in others. One researcher was concerned not only with the variability among judges but also the inconsistency individuals displayed. Pointing to prior studies, he cited the lack of agreement among judges. His task, he said, was to see if tasting judges would replicate their scores when given exactly the same wine in a different flight (30 wines).

Many did not.

He observed that out of 65 panels of judges, 50 percent of the time, the score related primarily to the wine. In the other half though, other factors played a larger role. It could matter if someone was hungry or tired or feeling irritable. Only about 18 percent of the time, mostly for the wines they disliked, judges were perfectly consistent.

Our Bottom Line: Noise

For individuals and groups, scattered results can be called noise. Noise is composed of the disparate judgments that should be the same. Organizations experience “system noise” when their members form different conclusions about the same phenomena. Because some employees are more lenient or severe than others, opinions about payments from an insurance company depend on whom you ask. Medical diagnoses and stock evaluations differ. Some judicial decisions correlated to local team wins and losses or the time of the day. And yes, umpires and wine tasters disagree with others and themselves.

Because behavioral economists add a dose of psychology to economics, they provide more insight about the incentives that influence our decision-making. They are concerned with noise when it diminishes the accurate decision making that organizations require.

My sources and more: Nobel economics laureate Daniel Kahneman is the co-author of a new book, Noise, that he discussed with Katy Milkman in her Choiceology podcast. From there, it made sense to skim the wine judging paper and return to an econlife post on umpires’ calls (that I excerpted today).