In 2008, new stand-alone fast-food restaurants were banned in South Los Angeles. The City Council thought that less fast-food consumption would diminish obesity in low income neighborhoods. Years later, the media reported that the policy had little impact. Whereas the area’s obesity rate had been 63% in 2007, it rose to 75% by 2011.

Now, researchers suggest that we need not target low income areas when worried about fast food.

Fast Food Consumption

The conventional wisdom says that lower income households would buy more fast food because it was cheap. A new study indicates the opposite.

Scholars from Ohio State and the University of Michigan collected survey data about fast food from 8136 individuals during 2008, 2010, and 2012. Their goal was to see if the socioeconomic status of adults in their 40s and 50s affected their fast-food purchases. They asked, for example, how many times the person had eaten “food from a fast-food restaurant like McDonald’s, Kentucky Fried Chicken, Pizza Hut or Taco Bell” during the past week. They also had wealth and income facts that they could connect to the fast food answers.

It turns out that we all eat about the same amount of fast food. For the 3 weeks that were observed, the people in the lowest income bracket typically ate 3.6 fast-food meals, the middle, 4.2 meals and highest, 3. Among all respondents, 79% had eaten fast food at least once during the past week whereas 23% had purchased 3 or more meals.

They even concluded that fast food consumption went up with more income when they compared the lowest quintile to the middle. Then, going up further, it slightly decreased. The difference, from the least to most affluent was one fewer fast-food meal.

Instead, the research uncovered the correlation between time and fast food. People who had less leisure time because of work tended to eat more fast food. So too did individuals who drank more soda.

These Gallup numbers also indicate that low income and fast food have little correlation:

Our Bottom Line: Demand

For most items, called normal goods by economists, an increase in income leads to a rightward shift in a demand curve. Because we have more money, we are willing and able to purchase more goods and services that are more expensive.

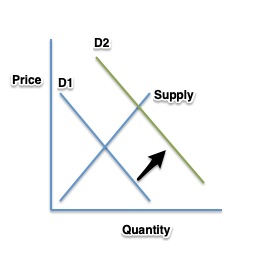

Causing an increase in demand for normal goods and services, more income would shift D1 (before) to D2 (after):

However, it is also possible but less likely, that the item is an “inferior” good. Referring to less demand, economists do not mean anything pejorative by inferior. They just want to tell us that inferior goods violate typical demand behavior. When our income rises, we buy fewer inferior goods. We no longer want cheaper, tougher cuts of meat or the most basic autos.

However, it is also possible but less likely, that the item is an “inferior” good. Referring to less demand, economists do not mean anything pejorative by inferior. They just want to tell us that inferior goods violate typical demand behavior. When our income rises, we buy fewer inferior goods. We no longer want cheaper, tougher cuts of meat or the most basic autos.

Causing a decrease in demand for inferior goods and services, more income would shift D1 (before) to D2 (after):

So, where are we? As economists, we could say that fast food is not an inferior good. And for that reason, when we target fast-food consumption, we should think of everyone–not just an LA low income neighborhood.

My sources and more: Thanks to Marginal Revolution for alerting me to the new fast food news. From there, the best links I discovered were here and here.