Dating back to the Commissioners’ Plan of 1811, a typical block in Manhattan is a skinny rectangle. Urban planners point out that the design is boring. With no stars, ovals or memorable focal points, the city’s grid is aesthetically undistinguished.

But it makes sense economically.

Grid Economics

For pedestrians, Manhattan’s street grid is easy. Navigation is simple along sequentially numbered streets. Although there are no time saving diagonals, length is manageable.

Because the blocks are rectangular, so too are most buildings. One scholar explained that a rectangular building would have rectangular rooms and rectangular furniture. I know this sounds simplistic but the concept makes for easily planned construction. It’s not difficult to add curbs and sidewalks. Meanwhile, block size encouraged an egalitarianism that attracted small businesses.

Comparing Manhattan’s blocks to Salt Lake City’s 660′ x 660′ squares, we can start to see why size matters. With such large blocks, Salt Lake City has fewer pathways for pedestrians. Its wide streets are much friendlier to cars than people.

Below you can see the difference:

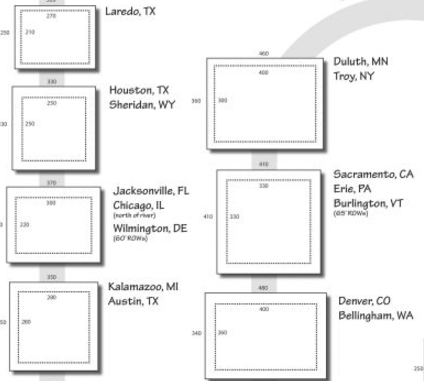

And here are some other cities:

Our Bottom Line: Externalities

Looking at urban development, we have cities that haphazardly evolved from the “bottom-up” like lower Manhattan and parts of Boston. Then, we have the “top-down” planning of most of Manhattan and Salt Lake City. And we have the top-down aesthetics of Washington D.C.

Whatever the plan, the one constant is the externalities. We can be sure that pedestrians and builders, lot owners, drivers and tax collectors will feel the impact.

And we can remember the difference that a rectangle makes.

My sources and more: Always interesting, 99% Invisible had a fascinating podcast on Salt Lake City’s street grid. The perfect springboard to the bigger picture, the podcast took me to this Yale paper and Manhattan’s original plans.