During the 1970s, China moved from a wan, xi, shao (“late marriage, longer spacing, and fewer children”) campaign to a one-child policy. Implemented locally, one-child was fueled by the law, community institutions, sterilization, abortion, and infanticide. Especially in the city, couples with more than one child could have lost a job, 10 to 20 percent of their pay, and even 40 percent of a year’s wages.

It took more than three decades for China’s leadership to decide that the tradeoffs were too costly.

In 2013, the government said two children were permitted if one parent was an only child. Then, two years later, all couples were allowed to have two children. And now, a three child limit will soon start.

The reasons for the reversal related to babies, boys, and the elderly.

6 Facts: China’s One, Two, Three-Child Policies

1. Babies: the rate

From more than six babies per woman in the 1960s, China’s birth rate steadily slid from 2.1 by the mid-1980s to approximately 1.3 in the 1990s. Then, when two-child was announced, they got a slight bump to 1.51 in 2017 but the dip resumed, falling to 1.47 per woman in 2019.

The total fertility line went below replacement by 1990:

2. Babies: the numbers

Correspondingly, the number of babies plunged. It decreased to 12 million births in 2020 from 14.65 million in 2019 and 17.86 million in 2016.

You can see the descent:

3. Boys: the numbers

With boys the preferred single child, this year’s distorted gender ratio is 111.3 boys to 100 girls. In 2011, it was a whopping 118.1 to 100. Having many millions of extra men has created its own challenges. Economists have observed that savings and housing values have risen because men have had to make themselves more desirable. A more affluent man with a home might have more of a chance of snagging a wife.

4. Boys: little emperors

We can add worries about entrepreneurship. Some say boys who are only children become “little emperors” who sidestep competition and risk. Also, younger people tend to be the most enterprising. By diminishing that segment of your population, you might be constraining your economic growth.

5. Elderly: the numbers

China now has more elderly people than children (aged 15 and under). Ascending, the share of China’s 60+ population moved from 10.45 percent in 2005 to 14.7 percent in 2013 and 18.1 percent in 2019.

The 2018 projections (below) remain valid:

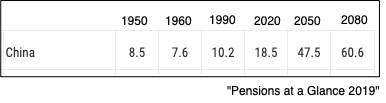

6. Elderly: dependency ratios

Whereas China was worried about too many children, now the concern is too many old people. As a result, there will be relatively fewer individuals in the working population to support pensions and social security for those who are no longer employed. Or as Philip O’Keefe, human development sector coordinator at the World Bank in Beijing said, “For the first time we are seeing a country getting old before it has gotten rich.”

The following old age dependency ratios (comparing the elderly population to the working population) are for the past, now, and the future:

Our Bottom Line: Population Growth

It all adds up to slower population growth. When we decompose the numbers, and look at babies, boys, and the elderly, we see their massive impact.

My sources and more: Ranging from FT to Project Syndicate, WSJ, the BBC, and the NY Times, the facts on China’s child policies were everywhere. I also had the pleasure of an afternoon with Princeton’s China expert Gregory Chow (now 90) and referred to his textbook on China’s Economic Transformation for this post.