With a “not-so-frozen-north,” we can start to think about the Arctic’s shipping lanes.

But before moving forward, let’s look back.

New Shipping Lanes

The 18th Century

When its construction began during 1817, the Erie Canal was a technological marvel. Connecting eastern markets with western farmers, it was the first big link in a transportation network of copycat canals that created a U.S. national market.

Although the Erie Canal extended 363 miles through New York State, its reach was far beyond. It enabled the port of New York to connect with points north and south. It brought the Great Lakes closer to the far west.

Because of a canal network, each part of the nation could specialize in what it did best. The Northeast could concentrate on manufacturing, the West could grow farm goods and raise livestock, the South could focus on cotton. What you did not provide locally, you could get from a distant place. Rocky New England farms no longer needed to grow tobacco. People in the South could stop making their own shoes.

At the same time shipping became cheaper and faster. To transport freight 100 miles by land during the early 1820s would have cost $32 a ton. By canal, the expense dropped to $1 per ton. Several decades later, in 1852, moving over rivers and canals between Cincinnati and New York City, freight arrived in a relatively brief 18 days.

The 21st Century

We can ask if the 21st century Arctic could create the Erie Canal phenomenon.

Let’s start by just thinking about old and new ice. Thirty years ago, 30 percent of the Arctic Ocean’s pack ice was at least four years old at the end of the winter. Now, replaced by new ice that is thinner and melts more easily, most of the old ice is gone. We also have higher average temperatures, less permafrost, and a snow cover in the Eurasian Arctic that melts faster and sooner because of the warmer temperatures.

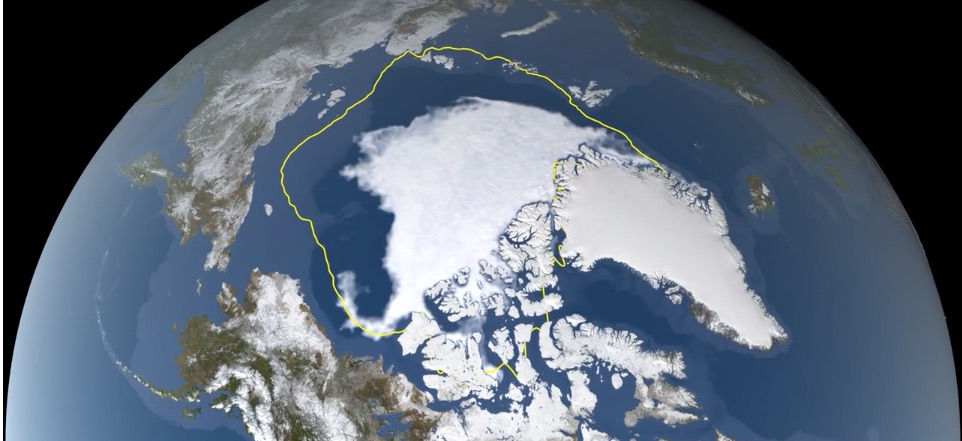

Below, you can see a shrinking Arctic ice and snow cover:

At this point, we can ask whether we wind up with navigable water which new shipping lanes will populate. The answers I discovered are, “not yet.”

We still have blustery weather and enough ice remaining that shipping would not be dependable for massive container ships. We have seasonal routes whose opening times will vary. In addition, the cost savings depend on the route. It will be a plus for shipping Russian Arctic oil and gas to Asian destinations and moving between Northern Europe and East Asia. However, other more distant countries would not benefit. In addition, we can continue to worry about oil spills and Titanic-like catastrophes.

A bit dry but worth your time, This 3-minute video presents a good summary of Arctic shipping:

Our Bottom Line: Infrastructures

An infrastructure is just a network. Composed of banking institutions, the network is a financial infrastructure. The internet is a big part of our information infrastructure. And, during the 18th century, the Erie Canal spurred the emergence of a network of transport arteries that spawned economic growth and the extension of our transportation infrastructure.

Still growing, our transportation infrastructure will include the Arctic’s new shipping lanes. But it will take awhile.

My sources and more: This NY Times article perfectly complemented all you can read from The Arctic Institute (whose newsletter I just subscribed to). As for the story of DeWitt Clinton and the Erie Canal, I hope you will read my book, Econ 101 1/2. Out of print, it is available on Amazon. I am working on an updated version.

Our featured image is from the NY Times. The yellow line shows that the Arctic’s 30 year average sea ice minimum far exceeds its current level. Please note also that several of today’s sentences about the Erie Canal were from a previous econlife post.