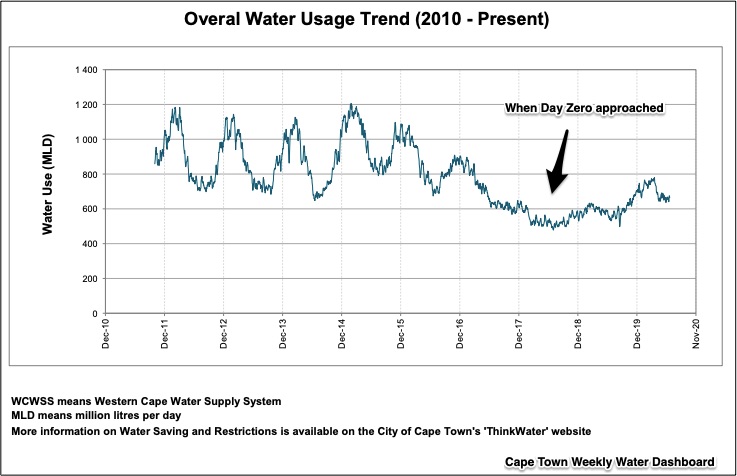

In 2018, Cape Town, South Africa was three months away from Day Zero when the taps would have run dry. So they set records for fast showers and washing shirts. To encourage less flushing, they were told, “If it’s yellow, let it mellow.” Washing cars and filling swimming pools were prohibited and water pressure was set at dysfunctionally low levels. The goal was to encourage conservation by making water use more costly.

It worked (and it rained).

I took a look at this week’s Cape Town Water Dashboard. The graph tells the story. You can see that they’ve become “water-wise”:

Where are we going? To the water tradeoff between conservation and affordability.

The Water Tradeoff

Affordability

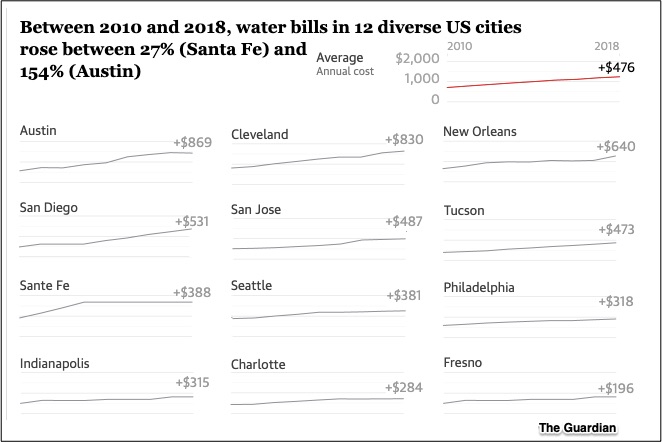

According to a new study covering 2010 to 2018, the cost of water has gone up in 12 U.S. cities. In dollars, we are looking at an average increase from $566 to $1435:

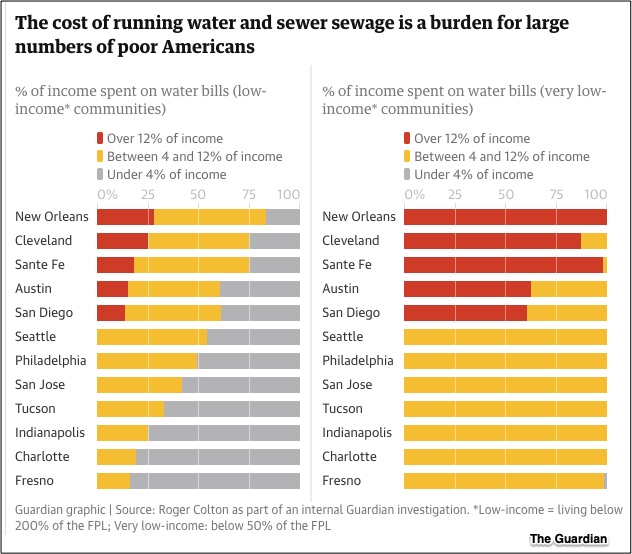

The big concern though is affordability. When water related bills ascend to 4 percent of a household’s income, it approaches the point of not being affordable. Comparing the rising cost of water and sewage bills to residents’ income, affordability becomes the big issue in New Orleans, Cleveland, Santa Fe, Austin, and San Diego:

Thinking of Cape Town and 12 U.S. cities, we wind up with a water tradeoff. We want water to be affordable and yet when it is, the incentive to conserve diminishes.

Our Bottom Line: The Diamond Water Paradox

Adam Smith wondered why water costs much less than diamonds. After all, we need water to survive while diamonds are merely an extravagant luxury. Years later, economists had the answer.

They just had to think at the margin, about the cost of the next extra unit.

With water, when there is a lot, the next extra glass, or flush, or shower costs little. Totally though, water is priceless. With diamonds, the opposite is true. We would rather have that one extra diamond and will pay a lot for it. But, the total usefulness of diamonds is small compared to water.

Economists here say that we are comparing marginal utility to total utility—the usefulness of the next extra unit that we consume to its total usefulness.

When the residents of Cape Town believed Day Zero was imminent, the marginal utility of water soared and usage plunged. We can worry though about that tradeoff in 12 U.S. cities.

My sources and more: The Guardian was a good starting point with the up-to-date study on the cost of water as was circleofblue and the Cape Town Dashboard. Looking back, WEF told how Cape Town averted Day Zero. Meanwhile, if you want more on water, diamonds, and the paradox of value, econlib is always a handy destination. (Please note that some of Our Bottom Line was in a previously published econlife post.)

And finally, if you have a spare 18 1/2 minutes do look at the following Netflix analysis of the world’s water problem. Insightfully, at the end they point out the fundamental contradiction. If we make water affordable, then the incentive to conserve diminishes: