For several years, I’ve listened to “page-turner” best-sellers when I do the dinner dishes. As Tom Hanks read Ann Patchett’s The Dutch House, I actually looked for extra plates to wash. Somewhat similarly, I get myself to lift weights regularly by leaving 6- and 10-pounders on my closet shelf.

The page-turners and the closet shelf are commitment devices. Called temptation bundling and piggybacking by behavioral economists, they can help us keep our New Year’s resolutions.

New Year’s Resolutions

Temptation Bundling

With temptation bundling, we combine our “wants” and “shoulds.” Temptation bundling limits the time used for your indulgent wants while encouraging a distasteful activity that will be good for you. You wind up with less of the “wants” and more of the “shoulds.” Done alone, each activity has less utility. Done together they create a value boost.

The Experiment

To see if temptation bundling had academic resilience, researchers divided 151 people who wanted to exercise into two groups. One group received iPods loaded with tempting page-turner novels that could be accessed only at the gym. The second group didn’t have the book incentive.

The results confirmed most of what we would expect. Group 1’s workouts exceeded the control group by 27%. So yes, temptation bundling did increase the frequency of the undesirable activity—the “should.” However, we should note that it didn’t kickstart a permanent workout regiment. After a temporary Thanksgiving break, neither group displayed “staying power.”

Piggybacking

With piggybacking, we “attach” a new task to one that we habitually do. The result is a cue. After accomplishing what we usually do, we have something that is supposed to come next.

The Experiment

In one study, researchers looked at flossing. Wondering what could get us to floss our teeth regularly, they used when as the key variable. The experiment had two groups of flossers. One was supposed to floss before brushing their teeth and the other, after. The power of the piggyback was confirmed by the experiment. The “after” group not only flossed more during the test period but more of them did it in the 8-month follow-up.

Our Bottom Line: Commitment Devices

Temptation bundling and piggybacking are two of many commitment devices. Defined by behavioral economists, commitment devices are incentives that encourage us to stick with an activity.

Other devises?

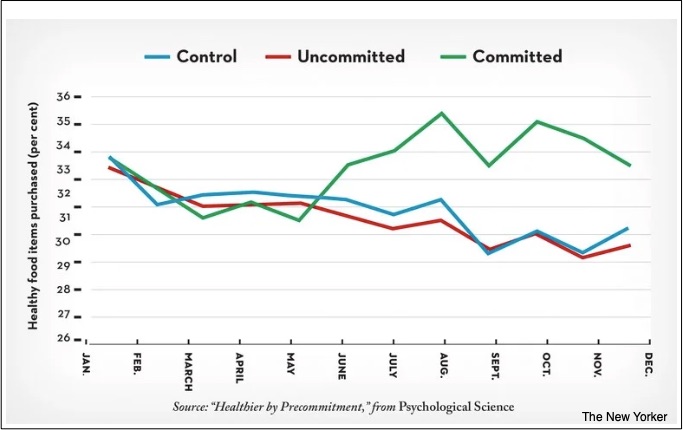

The New Yorker called it the Ulysses Strategy. When graduate students opted for a monetary punishment if they did not buy healthy food, the incentive had an impact among those who committed:

In addition, smaller plates at a buffet can make us take smaller portions. Another possibility is placing money into a deposit contract that requires forfeiture if you don’t carry out your end of the bargain. Also, those year-long gym memberships are an example (unless you’re one of those typical individuals who still doesn’t go).

For me, temptation bundling (the dishes) and piggybacking (the weights) so far work. I guess we each can choose the commitment device that perpetuates our New Year’s resolutions.

My sources and more: In The Washington Post, Penn Professor Katherine Milkman takes us to several commitment devices. Much drier, the academic formula for health interventions is described in this paper. Then, for a fast read, here is a brief summary of a flossing study. However, the best sources that combined the academics and some fun were Freakonomics and The New Yorker.

Our featured image is from Gerd Altmann at Pixabay.

This was an updated version from last year. I hope you enjoyed it.