Looking back at presidential elections, in 1960, we would have heard John F. Kennedy promise “to get the country moving again.” In 1980, with the Misery Index soaring (inflation plus unemployment), Ronald Reagan beat Jimmy Carter. And then, in 1992, Clinton advisor James Carville summed it all up when he said, “It’s the economy stupid.”

But it’s not that simple.

The Economy and Voting Patterns

Three new papers suggest the destiny of a political candidate may be about more than inflation, unemployment, and the GDP. They look at automation, globalization, and housing.

Automation

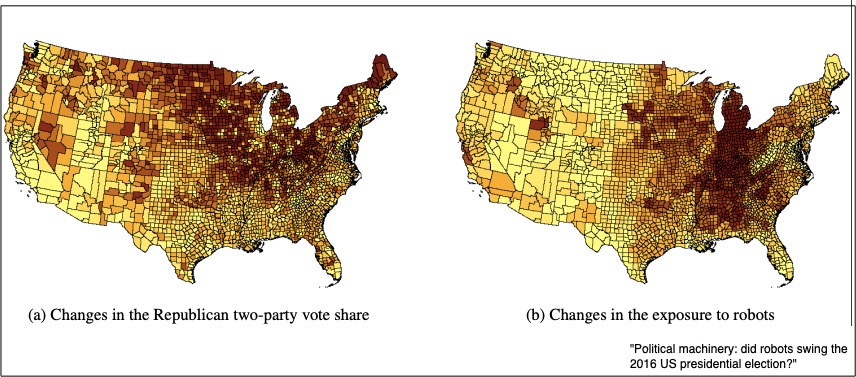

In a 2018 paper, three economists from Oxford University suggest that technological change can radicalize voters. First they look back at the workers that were displaced by the British Industrial Revolution. Next they consider how recent automation has reduced the incomes of blue collar workers without a college degree. And then they conclude that automation swung the 2016 vote to Donald Trump in Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin.

Comparing the 2012 and 2016 elections (below), the darker colors show where votes for the Republican Party and exposure to robots increased. In some of the same regions, there is an increase in both:

Globalization

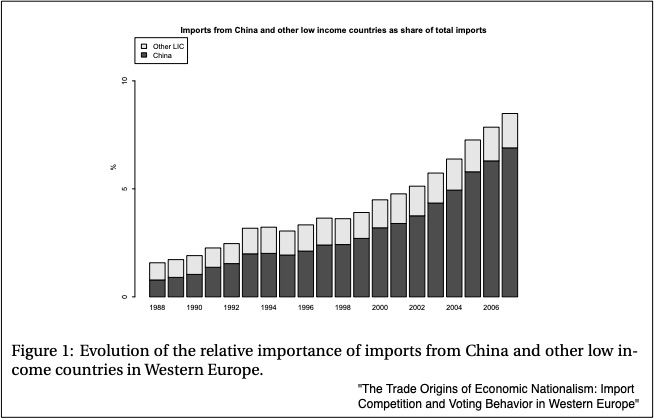

In “The Trade Origins of Economic Nationalism: Import Competition and Voting Behavior in Western Europe,” researchers looked at the elections in 15 European nations from 1988 to 2007. Similar to the automation study, they concluded that import shocks correlated to the increase in votes for nationalist parties that supported protectionist policies.

Below you can see the increase in the imports that led to economic nationalism:

Housing

When scholars looked at the 2016 Brexit vote and the 2017 French presidential election, they found a housing thread. In U.K. regions where housing prices tripled, there was a 16% higher vote against Brexit than where prices were level. Similarly, in France, higher housing prices and a higher Macron vote correlated. The reason? They hypothesize that housing, as a measure of local wealth, drives “the pattern of the populist vote.”

Our Bottom Line: Economic Statistics

So yes, the economy might still drive our voting patterns. Here though, we are influenced by the side of the economy that relates to robots, imports, and housing. As The Economist points out, “Voters care less than they used to about the economy’s immediate impact on their wallets. But they care more than ever about how the economy shapes their identity—their sense of security, and their freedom.”

All of this takes me to our macroeconomic statistics. We have said before at econlife that what we measure determines what we care about. Since voting patterns indicate we care about more than our quarterly GDP numbers and monthly unemployment, let’s emphasize additional numbers. Do take a look at the OECD Better Life Index. Based on your values, you can decide what you would include in your monthly measures.

My sources and more: Thanks to The Economist for alerting me to recent papers on the economy and voting. They referred to this paper on automation, this one on housing, and one on European nationalism. Then, while Pew Research had more on our attitudes about automation, this Washington Post column said it all.