Last week, President Trump released his budget for 2020. More than numbers, a budget represents policy, priority, and philosophy.

So let’s take a look.

The Trump Budget

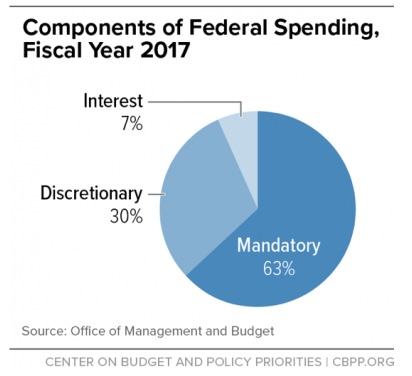

The President’s budget proposal reflects his goals for mandatory and discretionary spending. The biggest slice, the mandatory part, includes obligations perpetuated by law. Here we are mostly talking about entitlement programs like Medicare and Social Security. Meanwhile, the discretionary third (or so) of federal spending ranges from defense to education and the environment. A third smaller slice is the interest on the national debt. The debt has been growing because our spending exceeds our revenue. Consequently, we borrow more by selling government securities and owe interest in return for those loans.

You can see that mandatory spending is more than double the discretionary slice:

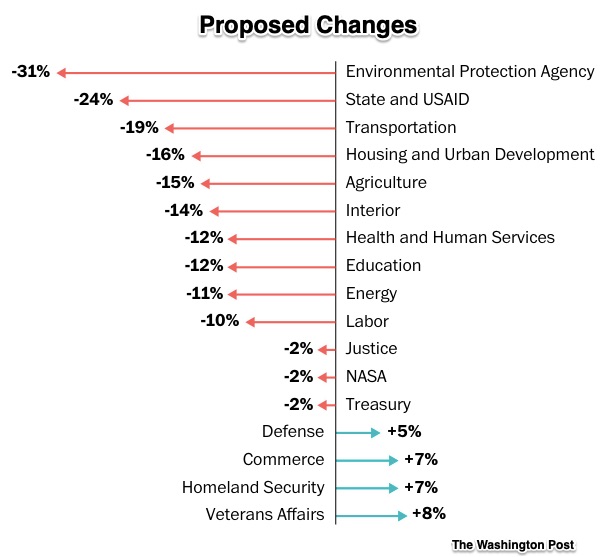

In the Trump budget, discretionary spending increases for defense and border protection reflect the administration’s priorities. However, do note that a large percent doesn’t necessarily mean huge dollars whereas a lower percent change can be massively expensive. The Environmental Protection Agency’s 31% decrease is $2.7 billion but the proposed 5% boost for the Defense Department is $33.3 billion. Still, losing a third or a quarter of your spending is a meaningful policy statement:

Our Bottom Line: The Federal Budget Process

This is only the beginning.

Now that the President has sent his 2020 budget to the Congress they are supposed to consider it. If approved (a huge IF), the budget kicks in on October 1, the beginning of the government’s fiscal year. Before then though, the House and the Senate create their own budget proposals. And then they have to agree on one budget resolution that really is just the overview. From there, the appropriations committees figure out the details.

We could say that the President “frames” the budget negotiations. Initially, he jumpstarts the process by submitting his budget. Then, at the end, he has to approve the appropriations bills that the Congress creates.

If you think all of this sounds daunting, it is. According to Pew Research, during the 42 years that this appropriations process has existed, the Congress met its Oct. 1 deadline only four times: 1977, 1989, 1995, 1997:

Based on Congressional budget history, we can assume again that the process will not quite work out this year. And, some of us might disagree with its priorities.

However, there is an upside. Because of the process, the President and members of Congress let us know what they care about. As economists, we can identify their tradeoffs.

My sources and more: The Washington Post did a good job of describing the big picture with their graph and the details through funding for every department. Next, the best picture of the budget process was from CBPP. Then the third piece of this puzzle came from Pew with budget history. I recommend all.