Because of the Silk Road, the West got silk and China tasted its first carrot.

Even before the ancient Roman Empire, the Silk Road’s mountain paths and sea routes were China’s trading lifeline. Traveling to Africa, Asia, and Southern Europe, traders exchanged commodities that ranged from carpets to cinnamon.

Now China is (sort of) resurrecting the Silk Road.

Six Facts About China’s Belt and Road Initiative

1. The name:

They call it their Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Belt refers to the land part and Road, the sea.

2. The location:

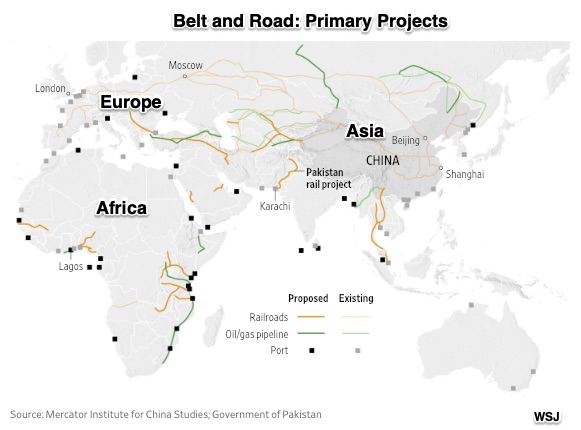

You can see that the Belt and Road Initiative touches three continents:

3. The plan:

3. The plan:

Like the old Silk Road, the basic goal is trade. Some say BRI is comparable to the U.S. Marshall Plan that funded European rebuilding after World War II. The big difference though is that the U.S. provided grants. Instead, involving 70 countries, China is planning to lend trillions for the creation of a massive infrastructure that includes highways, ports, and pipelines.

4. What China gets in return:

Then, China gets the money back through payments to the Chinese companies that will help to build it all. Also, by upgrading infrastructure, it can reduce trade costs and use new pipelines to boost its oil and gas supply. Completing the picture, China gets more demand for its goods and services in countries that become increasing affluent.

However, as Vox explains, there is still more that China has in mind:

5. What has been done so far:

First mentioned in 2013, the plan was released two years later. By 2018, these projects were entirely or partially completed. The labels give us a good idea of what is being done and where:

6. Problems in Pakistan:

With Pakistan a $62 billion example, China has hit some bumps in the Road (and Belt).

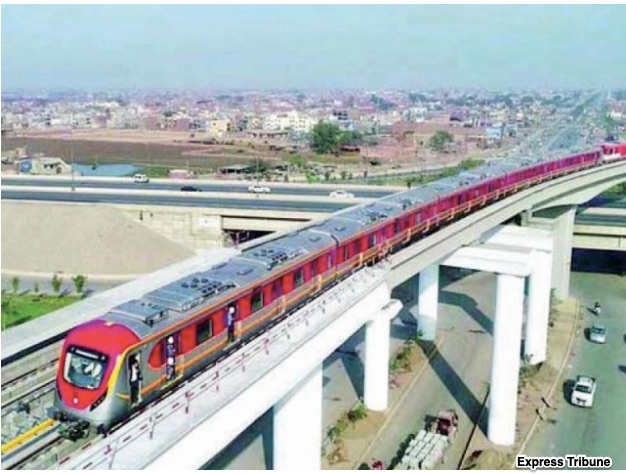

A $2 billion brand new air conditioned overhead railway will soon run through Lahore. Called the Orange Line, it was mostly built by Chinese SOEs (state-owned enterprises). Predictably, local companies wanted more of the business.

A computer image of the Orange Line:

There are also repayment concerns. Since Pakistanis underpaid their electric bills, the loan agreement for a Chinese funded electrical grid is not working out. To offset unpaid obligations, Pakistan gave China a 40-year lease to a strategically located port. Similarly, Sri Lanka gave China a 99-year lease to a port.

You can see why worries are building about Chinese influence, corruption, and a massive, unmanageable debt load.

Our Bottom Line: China’s Economic Model

During the past four decades, China’s productive capacity became increasingly sophisticated through a mixture of command and the market. The command side is dominated by SOEs–the state-owned enterprises that control key industries and finance. Indeed, if you looked at telecommunications, construction, banking, and other economic “pillars” you would see national and local governments running businesses that remain an important part of their economy. The interesting part though is that there is self-interest, competition, and wealth accumulation among a vast number of privately run companies.

Now we can add China’s need for markets beyond its borders. On the investment side, its SOEs have underutilized capacity that can be fulfilled elsewhere. Correspondingly, it hopes to create markets for its goods and strengthen its currency beyond its borders.

Vox summed it all up in three words: dominate world trade.

My sources and more: For some BRI history, the Peterson Institute is a good start. From there, WEF has an explainer. But for a more recent update and some insight, I recommend Vox, WSJ, and this article from the Pakistani media.

Please note that part of Our Bottom Line was in a past econlife post.