A year ago, China filed a formal complaint with the World Trade Organization (WTO). Targeting the European Union and the United States, China’s goal was to have its economy called a market.

The case is huge. Its results could transform the world economy.

China and the WTO

When China became the 143rd member of the WTO on December 11, 2001, it formally entered the global trading community. At the time, it had to accept a Non-Market Economy (NME) designation. The reason? Its trading partners assumed that China’s subsidies and price controls would lower the prices of its exports.

Called dumping, artificially low prices would enable Chinese goods to compete unfairly in world markets. As a result, the WTO said China’s trading partners could use a world price for goods to determine what production should have cost. Then, they could respond with tariffs and other trade barriers that the WTO would normally prohibit.

Fast forwarding to now, China says its NME status expired on December 11, 2016. Because the U.S. and the EU disagree, a panel at the WTO will settle the dispute. At stake for the U.S. and EU are many billions in tariff revenue and a massive influx of unprotected cheap imports. Easier access to Chinese markets is also an issue.

You can see below how China’s share of the world’s exports and imports has steadily risen:

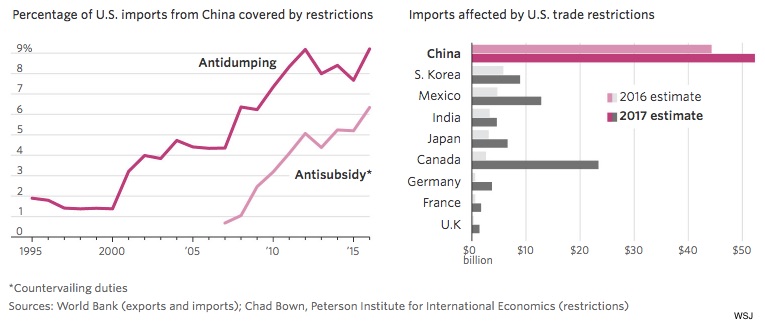

And how much the U.S. has used tariff barriers to protect goods that include steel, solar panels, and tires:

Our Bottom Line: What is a Market?

China likes to point out that New Zealand, Australia, Switzerland, and Brazil each say that China has a market economy. And yes, we can say that an increasingly large proportion of the businesses in China are privately owned. But then we also have to ask about government support for those businesses. We have to decide if their inexpensive loans, free land and subsidized capital offset all pretense of the market setting a price.

Perhaps we could imagine a continuum along which government involvement increases. The question is where to place the tipping point? Where does the market reach its boundary and a command economy start?

I assume the WTO panel will decide. Or it might just say the 2001 agreement had the 15-year expiration date.

My sources and more: I’ve begun listening to a Peterson Institute podcast series on international trade. Somewhat dry, the podcasts are magnificently enlightening. Their discussion of the EU case and China was excellent. Complementing the podcast, they have several papers here and here. Also, Politico, WSJ here and here, and FT had some good analysis.