Just like technology stocks in 2000 and housing in 2005, the cupcake bubble has burst.

In 2004 or so, many of us started buying the most amazing cupcakes. 4 inches tall, topped with sprinkles or a cookie, the cupcake might have been pistachio or strawberry vanilla and the filling, maybe custard or cream or fudge. We were willing and able to pay $4 for one cupcake or even $42 for a larger size that served 6 or 8.

As prices rose so too did the quantity supplied. Online, from small shops, from chains, in restaurants, gourmet bakers multiplied. Easy entry is what an economist would say about the market.

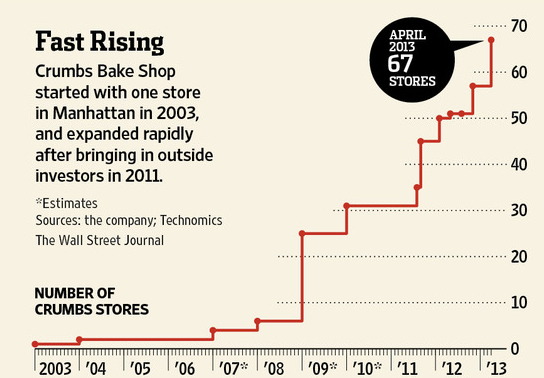

A cupcake shop called Crumbs opened 11 years ago on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. By April 2013, they had 67 stores in more than 10 states. Yesterday, Crumbs announced they were closing every shop. (They even tried selling the crumbnut–a croissant donut, aka the cronut--but that did not save them.)

Crumbs’s rise was meteoric.

In the US, a list of bubbles would include 18th century government bonds, 19th century railroads, and 20th century stocks.

From James Surowiecki’s The Wisdom of Crows, I discovered that we even had a bowling bubble. In 1936, Gottfried Schmidt invented the first automatic pinsetter. With machines replacing pin boys, after World War II, bowling boomed and Wall Street responded. As a young Charles Schwab said, “Compute it out–180 million people times two hours per week, for 52 weeks. That’s a lot of bowling.” The result was soaring stock prices in firms such as AMF and Brunswick and the bowling bubble. By 1963, though, following the path of all bubbles, the market reversed and prices plunged to 20% of their all time highs.

Our bottom line: Whether looking at cupcakes or houses or bowling, bubbles tend to start with unrealistic optimism and demand driven price increases. Then, as speculative purchases escalate, sooner or later, the market touches its peak, reverses, and dives downward. On the way up, participants like to say “This time it’s different.” But it never is.

The Cupcake Bubble

Elaine Schwartz

Elaine Schwartz has spent her career sharing the interesting side of economics. At the Kent Place School in Summit New Jersey, she was honored with an Endowed Chair in Economics. Just published, her newest book, Degree in a Book: Economics (Arcturus 2023), gives readers a lighthearted look at what definitely is not “the dismal science.” She has also written and updated Econ 101 ½ (Avon Books/Harper Collins 1995) and Economics: Our American Economy (Addison Wesley 1994). In addition, Elaine has articles in the Encyclopedia of New Jersey (Rutgers University Press) and was a featured teacher in the Annenberg/CPB video project “The Economics Classroom.” Beyond the classroom, she has presented Econ 101 ½ talks and led workshops for the Foundation for Teaching Economics, the National Council on Economic Education and for the Concord Coalition. Online for more than a decade. econlife has had one million+ visits.