Looking back at song length, we would also see the technology change. In 1964, the Temptations My Girl was relatively short. One reason could have been the capacity of vinyl records.

Do listen for three very pleasant minutes:

Then formats changed and so too did song length.

New formats:

Song length:

With streaming, songs are again shorter. One reason is the skip rate.

Shorter Songs

At 30 seconds, artists worry about the “skip rate” and then it’s the “non-complete heard” ratio.

For an artist to get paid, we have to listen to a streamed song for at least 30 seconds. After that, though, if we turn off the song too soon, Spotify and its sister streaming services toss it in the “non-complete heard” bucket where its rating sinks.

Down by approximately 40 seconds since 2000, songs have shrunk. Whereas the typical length had been in the vicinity of four minutes and 10 seconds, recently it declined to 3 minutes 15 seconds:

Our Bottom Line: Marginal Utility

As economists, we can say that those shorter song tracks create more marginal utility. By marginal we mean the next extra things that we do or eat or produce whereas utility is usefulness or satisfaction. More simply stated, marginal utility is just extra satisfaction.

When we think of music, on the supply side, those shorter tracks create extra streaming revenue, beyond the existing margin. Meanwhile, the demand side seems to like the brevity that represents a pull back from the old margin. It could reflect shorter attention spans that require an upfront “hook.”

So yes, streaming is a big piece of the shorter songs puzzle.

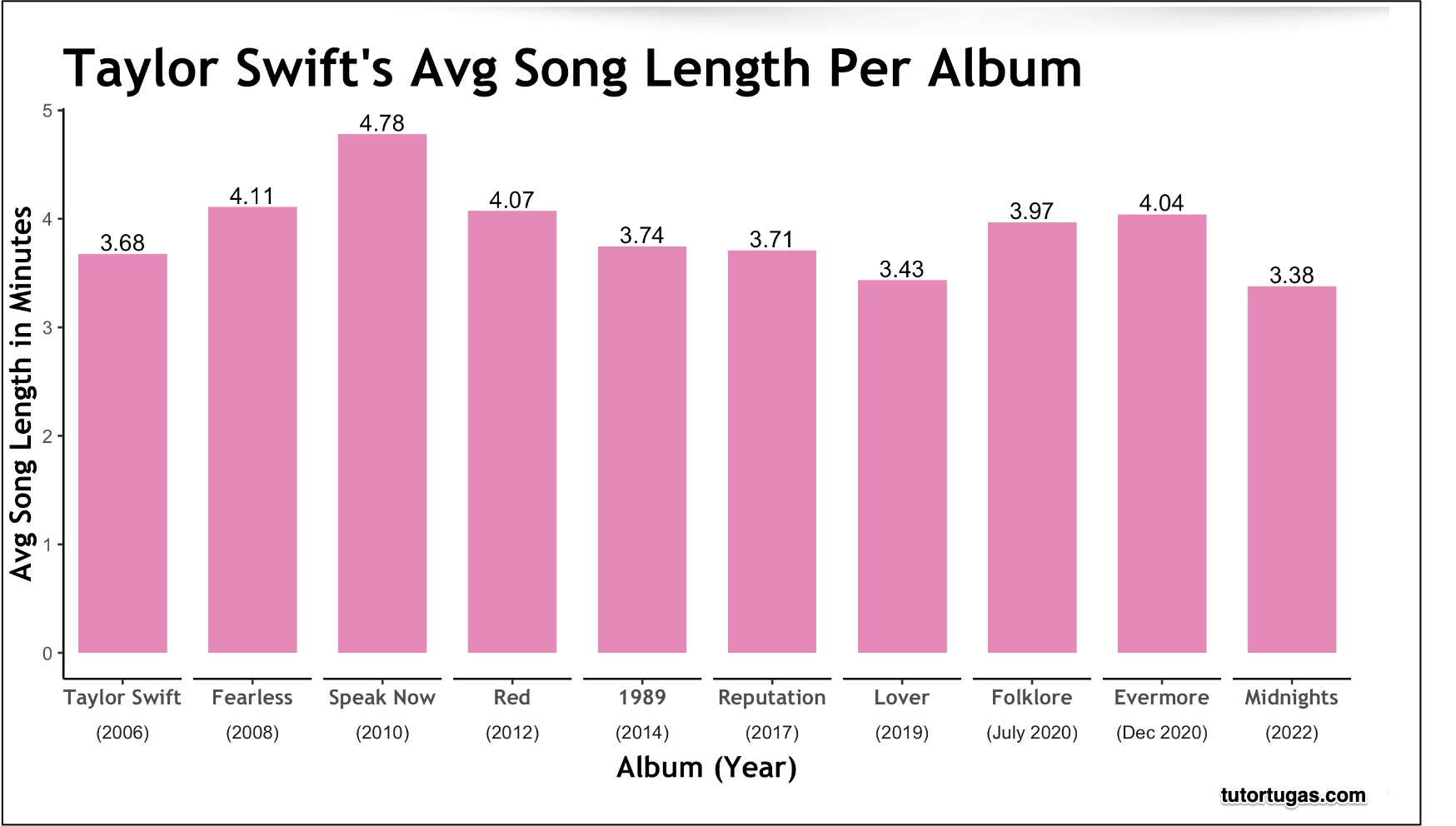

However, I wonder if Taylor Swift has slightly different incentives:

My sources and more: Thanks to WSJ for reminding me it was time to return to streaming incentives. From there, complementing WSJ, Billboard Pro had more of the details as did

Please note that parts of today’s Bottom Line were in a previous econlife post.