In Zimbabwe, a slice of cheese could be your change.

Zimbabwe’s Inflation

One woman told the Wall Street Journal that she paid $3.50 for some chicken, fries, and a soda with a $5.00 bill. Having no currency nor coins, the eatery could only offer a slip of paper saying how much she could use for her next meal. But she could not have used that IOU to pay for her bus fare.

Actually there were other possibilities. Instead of the “IOU,” she could have received approximately 1200 Zimbabwe dollars. However, they might have been worth less than $1.50 by the time she reached her bus. Another possibility was waiting for a subsequent diner that would pay with the $1.50 she needed. Then, the oppostunity cost was her time.

The woman’s plight is typical in Zimbabwe as they again work their way through their monetary mismanagement. Each time, since, several decades ago, Robert Mugabe printed the money he felt he needed, the country has turned on the printing presses and unleashed massive inflation. Then, the population has reverted to the U.S. dollar and, less confidently, the South African rand. Even worse though,they have not had all of the US dollars they needed nor the coins that might have facilitated smaller transactions in a nation where the daily income for 40% of the population is less than $1.80.

Laundered Money

One image econlife showed more than 7 years ago displays how they solved the problem of dirty, overused US dollar bills. It’s the new way to perceive laudered money:

As more than just a snapshot, laundered currency tells you the story of a troubled economy. Lacking a functional money supply, the country winds up producing less. And then lower production means layoffs and diminishing demand.

With prices doubling every 24.7 hours because of too much money in circulation, Zimbabwe’s inflation rate was 79.6 billion percent in late 2008. To reverse the plunge, in 2009 Zimbabwe replaced their own dollar with money from other countries. Since then, they’ve relied on the U.S. dollar, the South African Rand, and assorted foreign currencies.

No more.

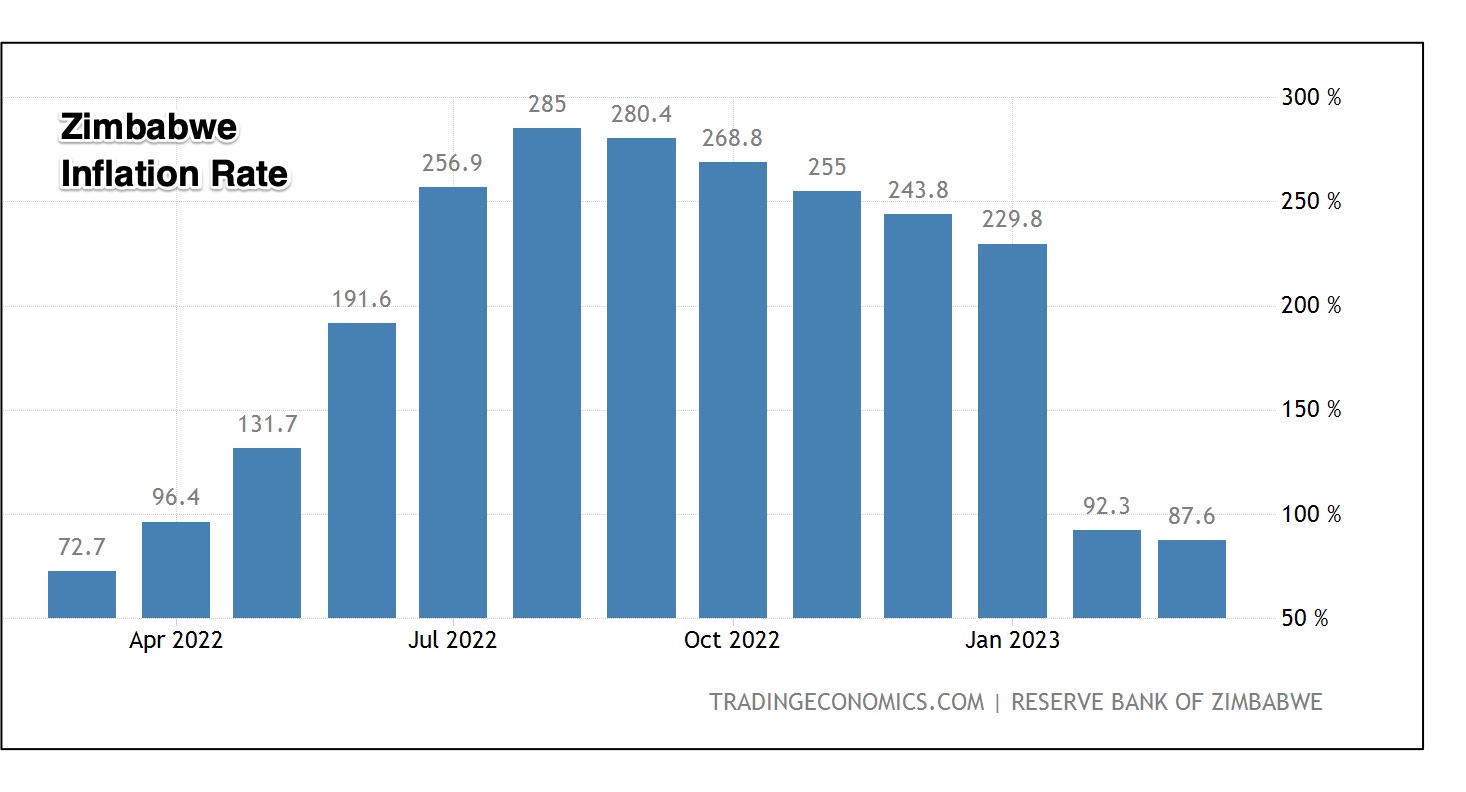

In 2019, they banned foreign currencies, issued a new Zimbabwean dollar, and created an electronic currency. Today we see that it did not work. A subsiding monthly rate is at a whopping 87.6%. Also, I am not even sure how they are measuring the rate because Reuters tells us that newly reported rates reflect a “blended rate” of the US and Zmibabwe dollars:

Our Bottom Line: What is Money?

Money can be rectangular squares of paper, tobacco leaves or cows. It can be backed by gold or silver or a bank or nothing. What matters is what people think. If we believe that a commodity is a yardstick of value, a medium of exchange, and can store value, then it functions as money.

Because few people believe that Zimbabwe’s currency is money, diners receive slices of cheese as their change..

My sources and more: Seeing this article in WSJ, I realized it was time to return to Zimbabwe. Then, For more detail on Zimbabwe inflation, do take a look at this BBC article, Al Jazeera, and for more recent facts, Reuters. Please note that today we’ve repeated several sentences from past Econlife posts.