Large corporations might be creating a much larger carbon footprint than their pledges seem to indicate. According to the New Climate Institute and Carbon Watch, 25 of the world’s largest companies could be fudging their progress. With Google saying it would be carbon free by 2030 and Ikea expressing a “climate positive” goal, the companies themselves identified their targets. However, what they actually say they will do accomplishes much less when we look at their direct and indirect emissions.

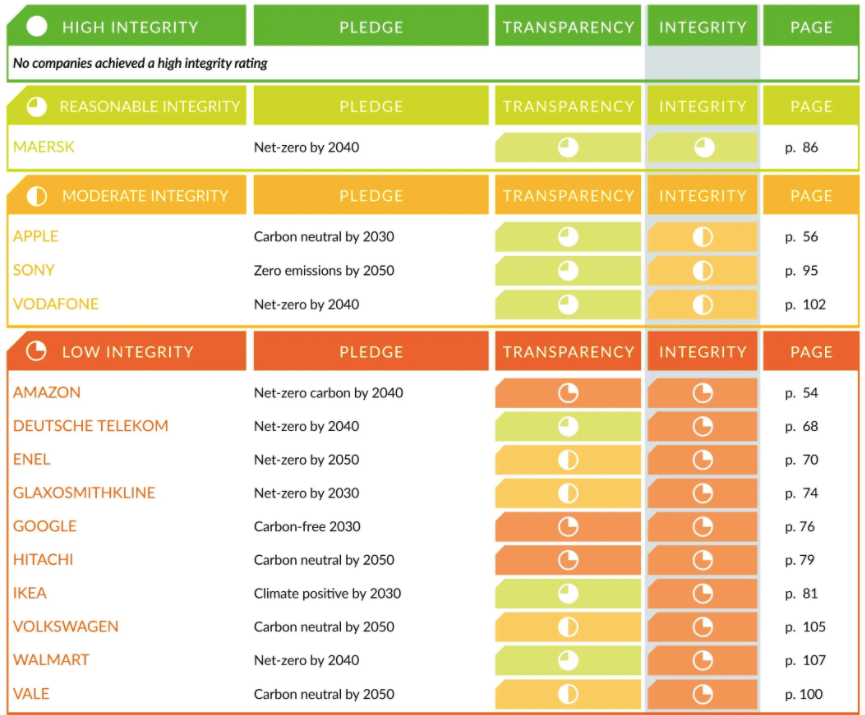

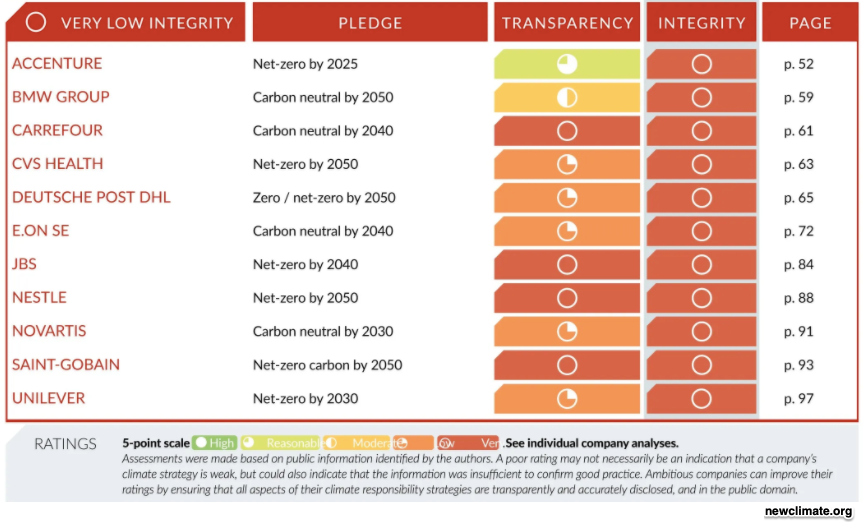

The New Climate Institute and Carbon Watch assessed the gap between what large corporations say and what they do with an “integrity” rating. The only one that came close to an “A” was Maersk. Otherwise, Apple received a “moderate” grade while Amazon, Google and Ikea were in the “low” category. Still lower, Unilever and Nestle were near the bottom:

At this point, we wind up with many questions. After all, when climate experts say that a liter of Coca-Cola creates 346 grams of carbon emissions, we cannot be sure what they included as it moves from the farm to a bottler to a supermarket.

That took me to the SEC.

Corporate GHG Emissions

As the chief regulator of the securities industry, the SEC is working on a climate change draft. The basic premise is that investors need to know standardized and accurate facts about a company’s exposure to climate change. But it’s not so easy to know what listed companies need to disclose and where they can be accurate.

As a part of its climate change draft, the SEC is probably debating three increasingly larger buckets. I suspect one is too small, the other too large and the third, just right.

- Called Scope 1, with the GHG data only on the company itself, the first bucket is the smallest.

- The largest one, Scope 3, reaches far beyond the firm to its customers and suppliers.

- Meanwhile, Scope 2 sticks with the company but includes the GHG it creates through, for example, the electricity it uses.

As you might expect, the biggest outcry is about Scope 3. Companies say they cannot be responsible for nor accurately report activities over which they have no control. The SEC also has to decide whether emissions disclosures belong in a financial filing or a separate document. The basic question though is when, where, and how GHG falls within the regulatory sphere of the SEC. This year, the SEC expects o have the answers.

Our Bottom Line: The SEC

Responding to conflicts of interest, inaccuracies, and fraud, the U.S. Congress created a securities industry watchdog in 1934. Since then, the SEC (Securities and Exchange Commission) has guaranteed that financial disclosure documents would say what investors needed to know and could depend on.

Since their creation, the SEC has had to adjust to new industries, new technology, new markets, new exchanges. With companies expressing data about the past, present, and future in their disclosure documents, certainly climate change has become relevant. Or, as SEC Chair Gary Gensler expressed “Companies and investors alike would benefit from clear rules of the road” that relate to how climate change affects a firm’s finances and risks. His goal is standardized disclosure that will be “decision useful.”

My sources and more: The BBC had the story from the Corporate Climate Responsibility Monitor while Reuters alerted us to the SEC’s emission reporting dilemmas. Then, for a deeper dive you might want to see the press release and the Climate Responsibility report. In addition, it was helpful to see how Coca-Cola does its own calculations and what a ratings firm looks at. Please note that several of today’s sentences were in a previous econlife post and our featured image is from econmatcher.com..