I just finished an omelette with eggs, broccoli, and goat cheese from a nearby farm. It tasted good, I supported local business and I helped the environment. You could say that I had my cake (but it was broccoli) and ate it too.

Not necessarily.

A Local Carbon Footprint

If you care about your carbon footprint, then eating local might not shrink it.

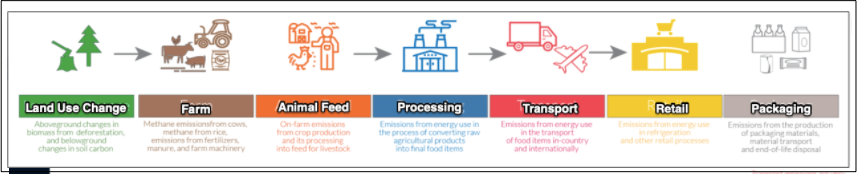

Yes, food miles do create greenhouse gases. But a study reported in Science tells us that the environmental impact of transporting food is relatively minimal. Less than 10 percent of the emissions from the global food supply (and .5 percent for beef), transport is not the answer. Neither is processing, retail, or packaging. Rather, the real culprits are dairy, meat, eggs, and the deforestation and cow burps (and farts) they create.

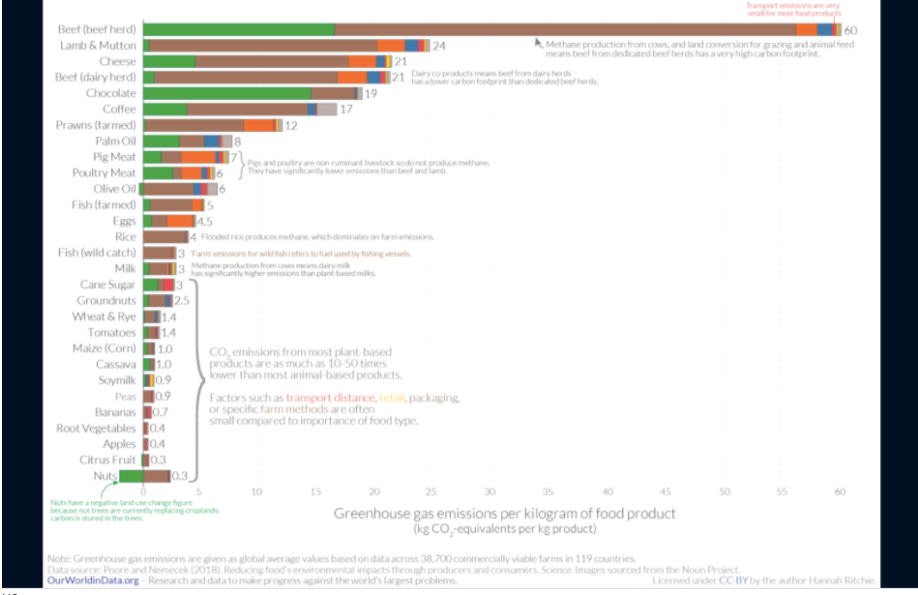

It all adds up to one kilogram of meat generating 60 kilograms of greenhouse gases. However, when composed of peas, that kilogram emits a single kilogram of greenhouse gases. Consequently, food production creates one-quarter of our greenhouse gas emissions.

Below you can see a food graphic that is based on food chain data from 38,700 commercial farms in 119 countries. Including 1,600 processors, researchers also looked at packaging and retail for 40 different agricultural goods. You can see that the impact varies substantially.

In the graphic, beef (beef herd) tops the list, Then we have lamb and mutton, cheese, beef (dairy herd), chocolate, and coffee. At the bottom, bananas are last and then peas and cassava. The surprises come from the green and brown bars. Green reflects “Above land changes in biomass from deforestation and below ground changes in soil carbon.” Then, the brown Farm rectangle represents “methane emissions from cows, methane from rice, emissions from fertilizers, manure, and farm machinery.” For beef and lamb/mutton, brown and green make transport emissions relatively teensy.

Our World in Data called their graphic “Food: greenhouse gas emissions across the supply chain”:

Our Bottom Line: Factors of Production

Being a locavore is not the key, even though, in 2007, locavore was the New Oxford American Dictionary’s “word of the year.” Instead, as economists, we can suggest that rather than where, it’s how. It’s about the land, labor, and capital that produce our food.

Still though, if you want to reduce your carbon footprint and believe in eating local, I suggest peas.

And not my cheese omelette.

My sources and more; Having last looked at locavores in 2012, it was time to return. From there, I discovered some up-to-date research from a group at NYU. The research was documented at Our World in Data but the whole paper was in Science and, un-gated, available through Research Gate. (Please note that I used several sentences from a past econlife for the beginning of today’s post.)