Last week, a NYC bank branch on Park Avenue temporarily ran out of $100 bills.

Routine transactions from ATMs were normal. It was just the large bills that had a surge in demand. One teller said the stream of customers was “nonstop” for cash.

During a disaster, stockpiling cash is not unusual.

The Demand for $100 Bills

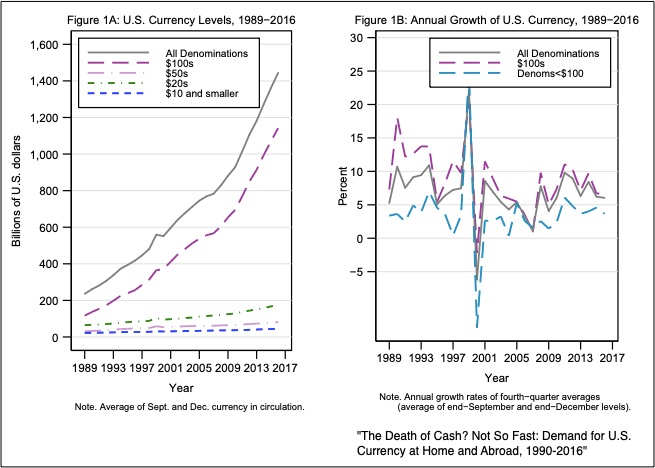

In a 2017 Federal Reserve paper, a researcher observed disaster patterns in currency demand. We had spurts during the 1990s when the Berlin Wall fell and the former Soviet Union collapsed. Again, reflecting the Argentina crisis in 1997, Y2K concerns, and 9/11, demand for U.S. currency surged. However, since late 2008, in the midst of the Great Recession, it has not subsided. Scholars cite a correlation between political and economic uncertainty and the global demand for the U.S. dollar.

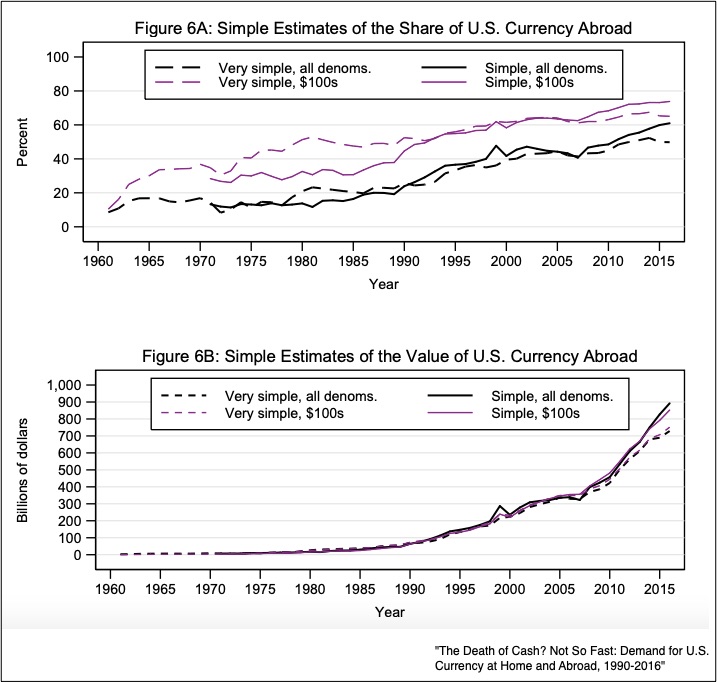

The U.S. currency that people want is the $100 bill. Last December, of the $1.7 trillion U.S. currency circulating, $1.3 trillion was in 100 dollar bills. And, 60 percent of U.S. currency and 75 percent of $100 bills were not in the U.S. (2016).

You can see that the ascent of the $100 bill far exceeds other denominations:

You can also see that a rising share of U.S. currency wound up abroad:

Our Bottom Line: The Money Supply

U.S. money is so appealing because it is a medium of exchange and a store of value far beyond U.S. borders. We need only add a unit of value and we have the three characteristics that make money, money.

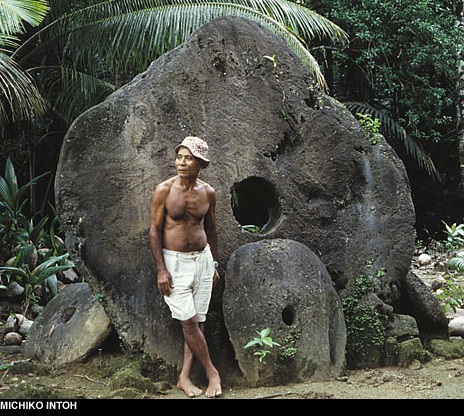

A little like our $100 bills, on the Pacific Island of Yap, huge, quite valuable limestone discs functioned as money.

Where are we? Returning to the NYC bank that ran short of $100 bills, we can add another example of the impact of the coronavirus.

My sources and more: The NY Times had the $100 bill headline while WSJ had more facts about cash. Then, for the academic perspective, you might read this Federal Reserve Paper. But, if you read just one article, do go to the Yap.