Please picture a jagged north south line dividing the US.

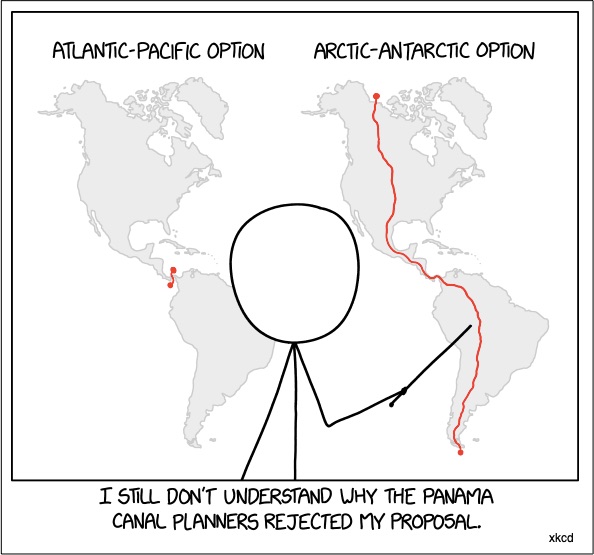

But not this one:

Located somewhere between the East and West Coast, this invisible line determines where supertankers carrying Asian cargo will dock. All places to the east of the line will receive goods from NY/NJ or maybe Savannah or Charleston. On the west side of the line, maybe Los Angeles or Oakland.

However, here is where it gets interesting. With the Panama Canal’s renovation completed in 2016, a newer, larger generation of Panamax container ships could use it. As a result, some of the cargo going to congested West Coast ports like Los Angeles have had a cost-effective alternative. Instead of landing in LA and then traveling eastward by train, cargo can head for the East Coast and then westward inside the U.S. Traveling between Shanghai and U.S. ports, using the Panama Canal instead of the Suez saves one week. It also became financially viable for exporters of liquified natural gas from Texas to use the Canal.

But now we have a problem.

The Panama Canal Slowdown

Structurally, the new locks are wider and deeper than the old ones. The size is necessary because new giant ships carrying 14,000 containers had not been able to travel through the canal:

Fed by a nearby artificial reservoir called Gatún Lake, normally the system has enough rainwater to sustain the canal because Panama is one of the world’s wettest countries. Now though, requiring an unimaginable 50 million gallons to float each vessel, its lock system has not had enough water. One reason is, El Niño.

On September 28th, we had an 89-vessel lineup at the Panama Canal. Because of an inadequate water supply, the Panama Canal Authority (ACP) had to cap the weight, the draft (how deep the ship sits in the water), and the number of ships in the Canal. Called a slow-motion catastrophe, the restrictions could last for an estimated 10 months.

Detours include moving shale destined for Korea or Japan around Cape Horn instead of waiting at the Canal. Others, unloading and then reloading the ship, have used the Panama Canal Railway.

The logjam has been compared to the Suez Canal blockage during March 2021.

Our Bottom Line: Canals

During the 19th century, the U.S. transportation infrastructure was composed of roads, canals, and railroads. However, our march toward a national market that linked the East and West was initiated by the completion of the Erie Canal in 1825 and then a slew of copycat canals.

Still today, reflected by the impact of a canal slowdown, we can see that canals remain crucial links in the world’s supply chains.

My sources and more: An article from the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) was the perfect place to start. Then, for more Canal history, do take a look at this past econlife post (from which I copied several of today’s paragraphs.) However, if you want all of the shipping detail and even Gatún Lake’s water levels, this website is riveting.