TBT: Dutch tulips, NYC cupcakes, Japanese and U.S. stock markets have all been rather similar.

Each became inflated.

Six Financial Bubbles

Dutch Tulip Bulbs

The tulip had first been introduced to Europe in 1559 or so—approximately when Elizabeth ascended to the British throne. Gathering popularity, especially in Holland, tulips had been displayed for their beauty. Eventually though, the quantity that was demanded exceeded the amount available. Unwilling to wait for a blossom, the rich and the poor started to trade the bulbs in markets that sprouted where buyers and sellers met. With buyers far outnumbering sellers, bulb prices skyrocketed.

In one tale, a seaman reputedly saw what he thought was an onion bulb in a wealthy merchant’s house. Given a juicy red herring to enjoy for breakfast, he thought the onion would be the ideal complement. So he popped it into his pocket and left.

Rather than an onion, the seaman had consumed a tulip bulb for which the merchant was said to have paid 3,000 florins–a huge sum of money in seventeenth century Holland. At that time, a suit would have cost 80 florins and one thousand pounds of cheese, 120 florins.

In February 1637, tulip bulb prices plunged. All who had dabbled in the tulip market suffered. Even if the sailor had never appeared, the merchant would have seen his investment evaporate.

First National Bank Stock

In 1791, after receiving Congressional approval for a National Bank, Alexander Hamilton approached the investing community. By selling bank stock to U.S. citizens and foreigners, he raised the money he needed for the bank’s vaults. Meanwhile, stockholders saw the chance to make some big money.

Within only several weeks, the price for one share of National Bank stock had risen from $25 to $300. Among the people who enjoyed this asset appreciation were 15 of the Congressmen who had voted to have a national bank chartered. Other stockholders included Harvard College, the state of New York, and William Duer, an Assistant Secretary of the Treasury under Alexander Hamilton. We could say that Wall Street was enjoying its first bubble.

Soon, the N.Y. Daily Advertiser warned Bank stockholders, “…What goes us must come down–so take care of your pate, brother Jonathan, ” And yes, trees don’t grow to the sky. There always comes a time when too many people want to sell. Before you know it you have many more shares for sale than people want to buy and prices plunge. Between August and September, 1791, the Bank bubble burst.

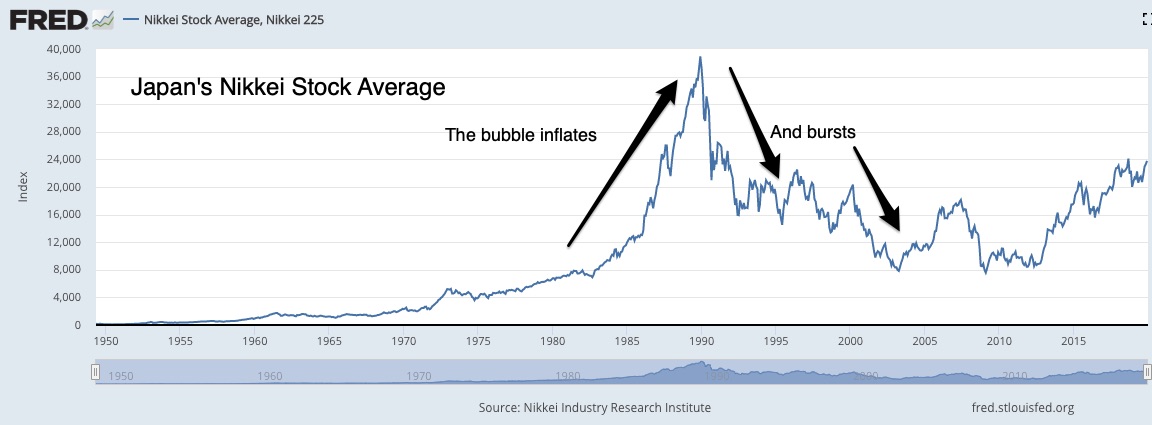

Japanese Stocks

Somewhat similarly, but two centuries later, Japanese stocks entered bubble territory. Had you invested $100,000 in one of Japan’s largest companies in 1970, by 1989, you would have had close to $5.7 million. The same investment in a small cap company became $18.3 million, But, as the Nikkei went up, share price increases raced ahead of the rise in corporate earnings. Visiting Japan, a U.S. commodities exchange president asked how the market’s ascending prices could be explained. His host replied, “You don’t understand…We’ve moved to an entirely new way of valuing stocks…”

It did not last.

The Nikkei stock market index touched 39,000 at the end of 1989. By 2008, the average was 7,000. First it soared and then it plunged:

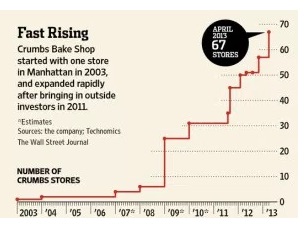

New York Cupcakes

In 1996 we had the first pricey cupcake. At a small NYC shop called Magnolia, the $3 gourmet cupcake was born. It took a chain called Crumbs, though, to inflate the bubble. Believing cupcake consumption was unstoppable, Crumbs’s production and prices shot skyward. They even sold a $42 cupcake that fed eight people.

Crumbs eventually had 67 stores:

The Huffington Post said we had reached “Peak Cupcake” when a Crumbs IPO (Initial Public Offering of stock to the public) let all of us join the frenzy. During June, 2011, the stock was $13.10 a share. Three years later, it had plunged to four cents a share and Crumbs shut down.

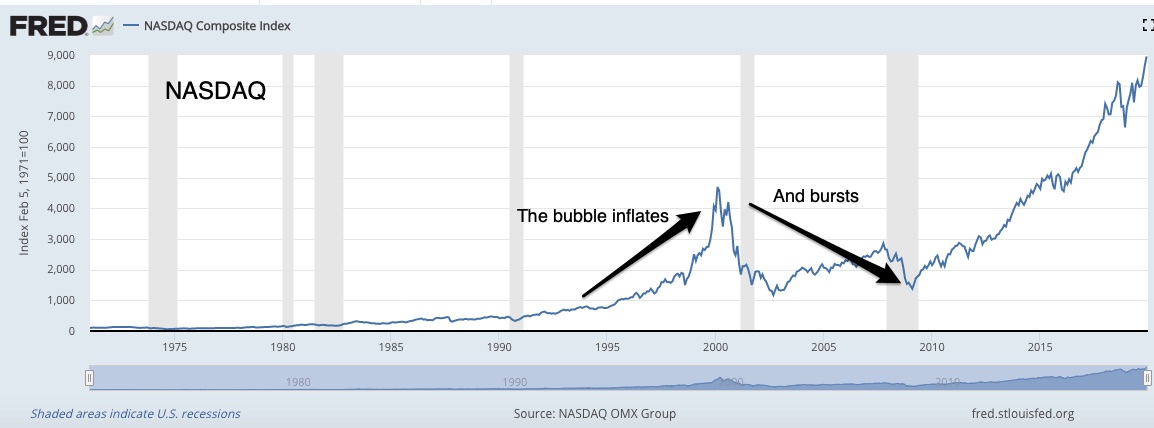

U.S. Tech Stocks

In 1998, an online pet store was a new idea that attracted millions in venture capital. With their Super Bowl ads and a Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade float, Pets.com created buzz. The firm went public in February 2000. Through their IPO and venture capital, they raised hundreds of millions of dollars. After hitting an IPO high of $11, the stock price sunk to 22 cents.

At the same time, other e-tailers were experiencing a similar demise. Few of us remember MotherNature.com, Garden.com, Drkoop.com. Dominated by sick tech, the Nasdaq composite more than halved. You can see the downdraft after its March 2000 high. From a peak near 4,696 on March 10, 2000, it dove down to 1,172 slightly more than two years later:

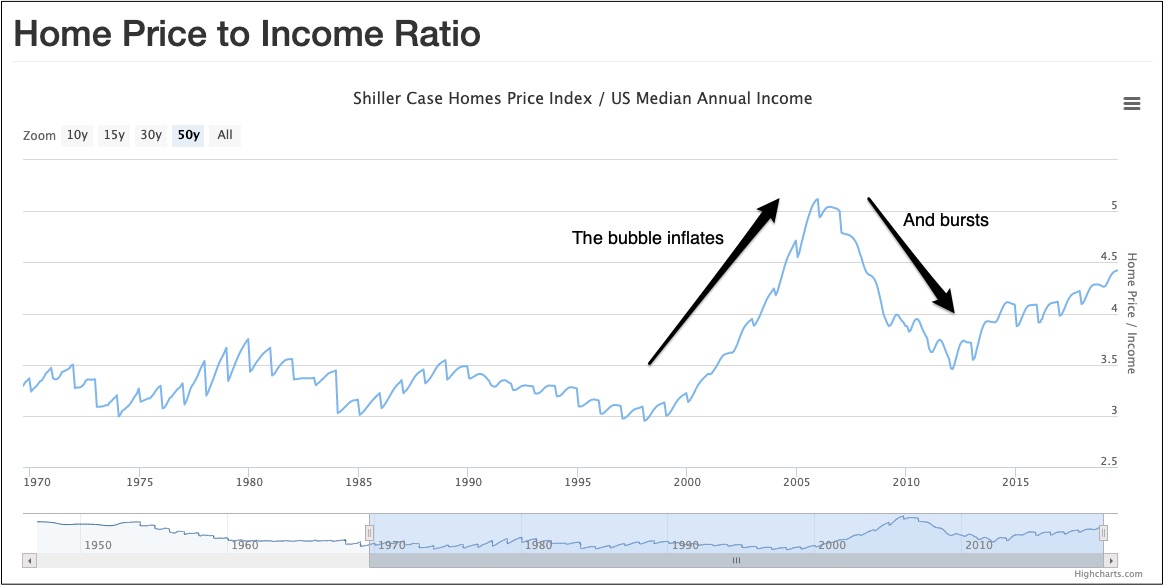

U.S. Real Estate

There is a quickie way to judge whether housing prices were irrationally inflated in 2006. We can just compare home prices to median family income. According to Brookings, the average ratio ranges from 2.5 to 4.0. However, sometimes low interest rates encourage buyers to ignore the equation. In 2006, the bubble burst:

Geographically, regions varied. You can see where the U.S. housing bubble was most inflated when it hit its 2006 highs:

Our Bottom Line: Financial Bubbles

We’ve covered centuries and moved from Dutch tulips to Japanese stock to U.S. real estate. Each one followed the pattern of a financial bubble. As euphoria builds, so too do demand driven price increases. Then, with speculative purchases escalating, prices move even higher. But always, the euphoria switches to panic, sellers multiply, and the market crashes. On the way up, participants like to say “This time it’s different.” They have relatively easy access to money. They enjoy irrational exuberance and believe puffed up growth stories. Inject all of that with a dose of moral hazard that obscures your risk and you get your bubble.

All of this takes me to a Bloomberg journalist who said last week, “The market feels as frothy as the top of a nutmeg cappuccino.”

My sources and more: Professor Jeremy Siegel’s Stocks For the Long Run is always an ideal source of market information. Then, for other bubble facts, Ritholz, Brookings, and Harvard’s JCHS had the analysis and data. But, if you read just one article, skip to how Bloomberg Businessweek wonders if we are sitting atop that frothy nutmeg cappuccino.

Several sections from today were in previous econlife posts. Our featured image is from Pixabay.