When people talk about the inadequacies of the GDP, they say it isn’t a measure of well-being. Measuring neither happiness nor satisfaction, it just conveys a money total for the value of the goods and services a country produces, typically during a year.

Today, let’s see if the GDP really does represent more.

Gross National Happiness (GNH) and Gross Domestic Product (GDP)

Bhutan’s GNH

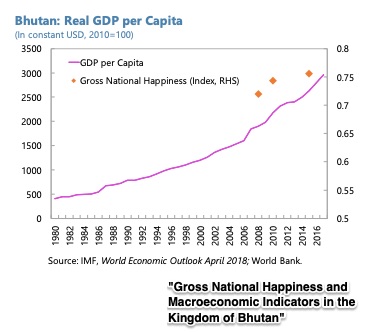

Located between India and China, Bhutan’s population is close to 725,000 while its economy is fueled by hydroelectric power, tourism, and agriculture. Most crucially, its per capita GDP has soared since 1980. Ascending from $400 to $2800, they have become a middle income nation.

Bhutan, however, measures its well-being differently from other developing nations. Yes, the GDP has been important as an economic common denominator for receiving aid. But, based on their Buddhist heritage, the Gross National Happiness is their key metric.

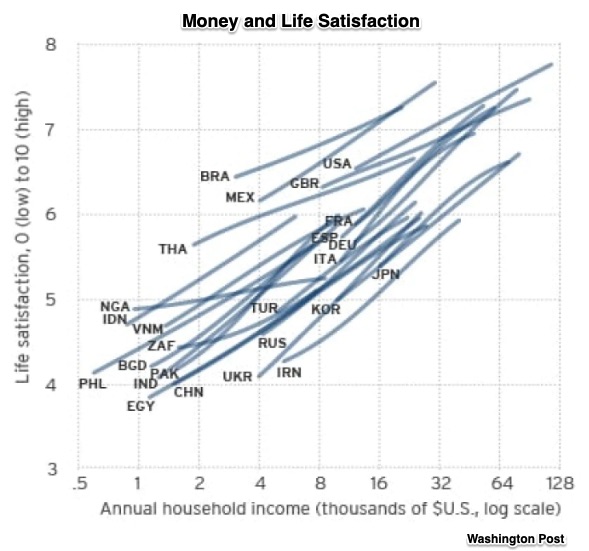

At first the GNH focused on happiness, not money. More recently, Bhutan’s statisticians added sustainability, climate change, and inequality to the happiness formula. Below you can see that the GNH is based on a hierarchy of concepts. The big ones are the pillars. They are divided into domains which are again divided. At the indicator level, we have the metrics through further subdivision.

This outline does a good job though of conveying the basics: Based on Bhutan’s 2015 surveys, 51% of the men and 39% of the women were happy or extremely happy. Looking at occupations, the farmers were the least happy. Correspondingly, people living in cities were happier than those in rural areas.

Based on Bhutan’s 2015 surveys, 51% of the men and 39% of the women were happy or extremely happy. Looking at occupations, the farmers were the least happy. Correspondingly, people living in cities were happier than those in rural areas.

Bhutan’s GDP

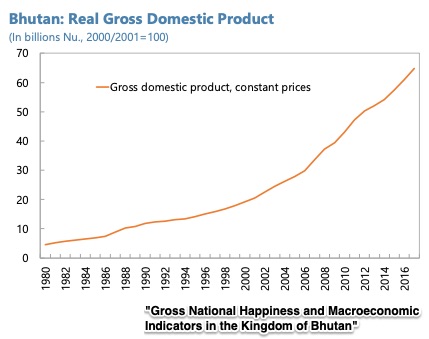

Next, we can look at Bhutan’s GDP and then compare it to GNH. Below, you can see that Bhutan’s GDP has gone up considerably between 1980 and 2017:

Compared to other countries, their growth rate is relatively high:

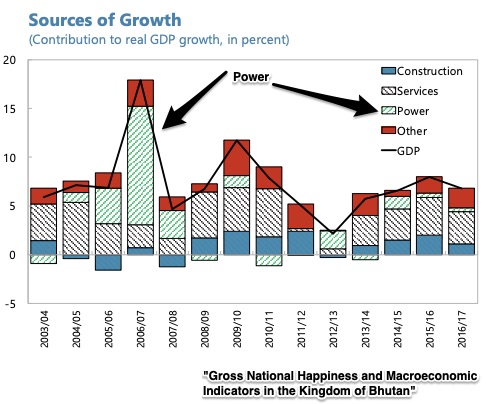

More precisely, Bhutan’s GDP rise has been attributable to energy:

More precisely, Bhutan’s GDP rise has been attributable to energy:

Our Bottom Line: The Connection

When researchers from the IMF (International Monetary Fund) tried to determine whether increases in the GNH and the GDP were related, they concluded, “…available evidence indicates that Bhutan’s rapid increase in national income is only weakly associated with increases in measured levels of well-being.” So yes, although both rose (below), they needed additional up-to-date numbers to confirm any causation:

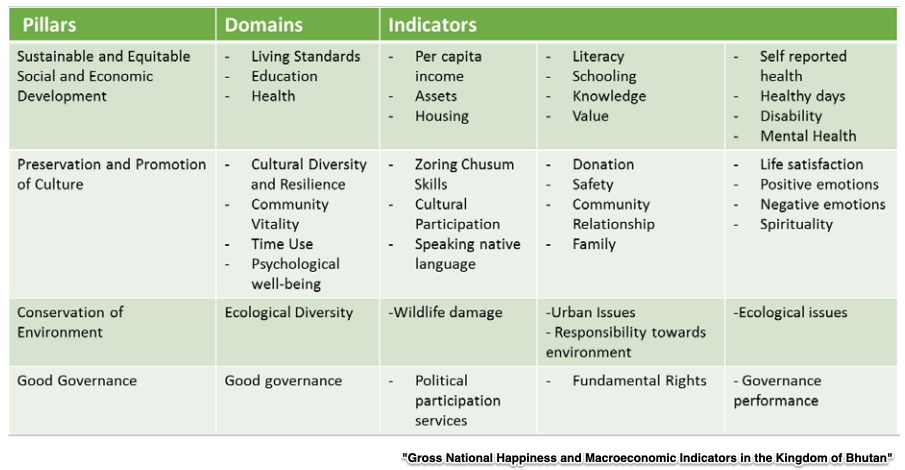

The researchers from the IMF are not alone. Economists continue to question the connection between GDP and happiness. The Easterlin paradox tells us that once basic needs are satisfied, more income brings no more happiness. Disagreeing, Justin Wolfers and Betsey Stevenson said, “…we find no support for this claim.” However, Wolfers and Stevenson take a baby step away from happiness by focusing on life “satisfaction.”

They say that a logarithmic scale proves their conclusions:

Today, the debate continues.

My sources and more: Thanks to Timothy Taylor at his Conversable Economist for alerting me to the IMF Bhutan paper (and offering his opinion–with which I agree–on the Wolfers and Stevenson/Easterlin debate ). Three complements were this Quartz article, this Tyler Cowen interview with Daniel Kahneman, and The Washington Post. However, If you really want to dig into the the debate, I suggest the Wolfers and Stevenson paper and this response from Richard Easterlin.