There once was a farmer who started to accumulate land in 2005 and now has 3,600 acres. While at first he planted wheat with a dilapidated tractor, now he has state-of-the-art John Deere equipment, top notch fertilizer, and up-to-date seeds.

Sounds like Iowa?

No, this wheat farmer is in Russia. His land is in the same place that Soviet collective farms called Lenin’s Path and Dawn of Communism had once underproduced. But this gentleman sounds like an entrepreneur. He works long hours, owns a fleet of trucks, benefits from a cheap ruble, and has access to improving storage facilities. In world markets he has been faring beautifully.

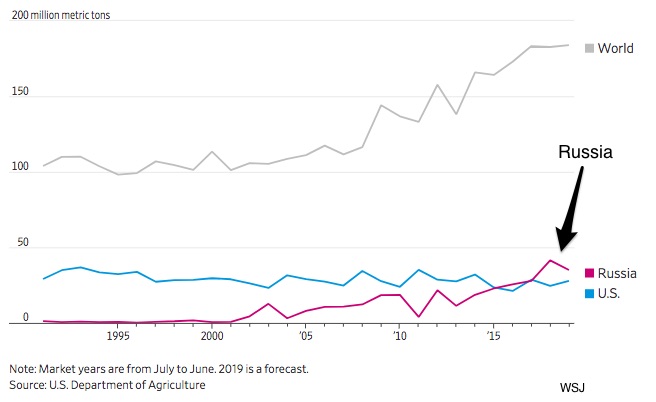

Russia just pulled ahead of the U.S. as the world’s biggest wheat producer:

Reading about this farmer in a recent WSJ article, I couldn’t help but think about how the Russian economy has changed.

Our Bottom Line: Economic Systems

We could say there are three basic economic systems. And Russia had all of them during the past 120 years.

Tradition

Looking way back at some Russian history, we could go to a typical pre-revolutionary estate owned by an exceedingly affluent family called Osorgin. Located 90 miles south of Moscow, their manor had eight villages, 8,327 acres, and 600 serfs. Its agricultural life was dominated by tradition. In traditional systems, land, labor, and capital produce the same goods and services year after year. Because roles are passed down from father to son and mother to daughter, all remains pretty much the same.

Command

Leaping to the 1920s, we have the Bolsheviks seizing farmland and the beginnings of a command economy. Through a series of five-year plans, the Soviets form a central planning apparatus that told people what and how to produce. As for agriculture, they created a network of collective farms where employees worked for a daily wage determined by economic planners. Individual initiative was disparaged and innovation was unnecessary. While Russia had been a major exporter of wheat until 1913, by the 1970s, they were unable to feed their entire population.

The Market

It took until 1991 for it all to collapse. With privatization, we get some capitalism and a wheat farmer who buys land, works hard, and flourishes. He employs ten farmhands, a cook and 3 guards.

Perhaps this entrepreneur is an unexpected ending to our 120-year Russian wheat story.

My sources and more: A WSJ front page article alerted me to Russian wheat. It also returned me to all that is fascinating about Russian history. I tell some of the story in my text, Understanding Our American Economy–available through econlife.