According to a parents’ advocacy group called Pregnant then Screwed, the cost of thousands of British women’s childcare exceeds their take-home pay.

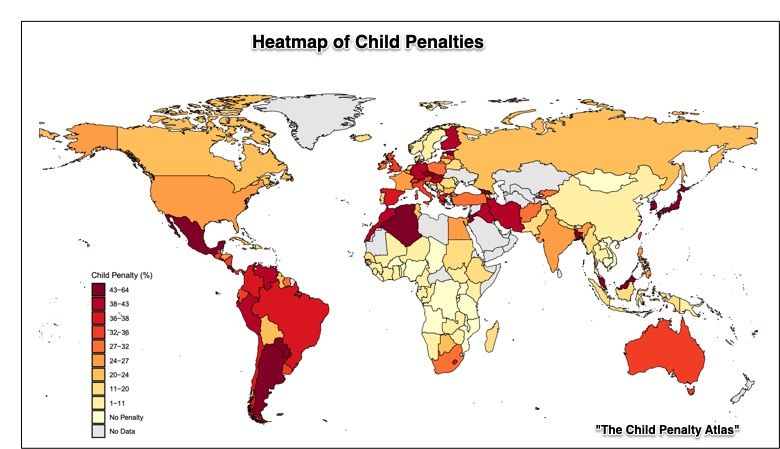

Including Great Britain, in 134 countries, we have a big (darker shades) and small (lighter shades) employment motherhood penalty:

The Motherhood Penalty

Quantifying the motherhood penalty, in a recent paper, scholars focused on women’s employment after the birth of their first child. As a result, moving from one year to five to ten, they calculate 24%, 17%, and then 15% left the labor force.

Globally, for women aged 25 to 54, 52% are in the labor force. As you might expect, with men, they pop up to 95%. Below, The Economist illustrates the impact of the first child on a woman’s labor force participation:

However, as always, a closer look reveals much more. In addition, we have to consider marriage and national affluence. In lower income countries, women leave the labor force after getting married. However, moving up to the middle income group, women tend to work after marriage but then, as a parent, they leave a job permanently. As for the richest cohort, it’s the birth of the first child that explains why women in high income countries are most likely to leave the labor force. At this point we could say that culture kicks in with social norms nudging women to stay home. And, we have not even considered the impact of urbanization that also boosts the child penalty.

Most crucially though, the authors of “The Child Penalty Atlas” provide more evidence than ever before of the probable causes of gender inequality. Having used data from 134 countries, for the first time, they’ve displayed the extent and depth of the impact of marriage and children. They show, for example, that the penalty can be small in some countries and massive elsewhere. Correspondingly, the child penalty helps to explain gender inequality in higher income nations but not for the lower income world.

Still, we could show the huge gap between Denmark, at a 14% penalty and the Czech Republic’s 50%. Or, for Bangladesh, it’s 62% and Vietnam, 1%. This Economist graphic displays the gap between Sudan and Taiwan:

Our Bottom Line: Confirmation Bias

I like to think that a confirmation bias is all about perpetuating a social norm. Its basic premise is that what we expect to happen, happens, because we expect it. With the motherhood penalty, if we are used to seeing women leaving work after childbirth, then it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Looking at the motherhood penalty in 134 countries, we certainly have history at work. Changing a tradition can be tough.

My sources and more: Summarizing the motherhood penalty, The Economist conveyed the basics and had the graphics. But most of all, I again appreciated this NBER paper’s immense amount of data and insight.