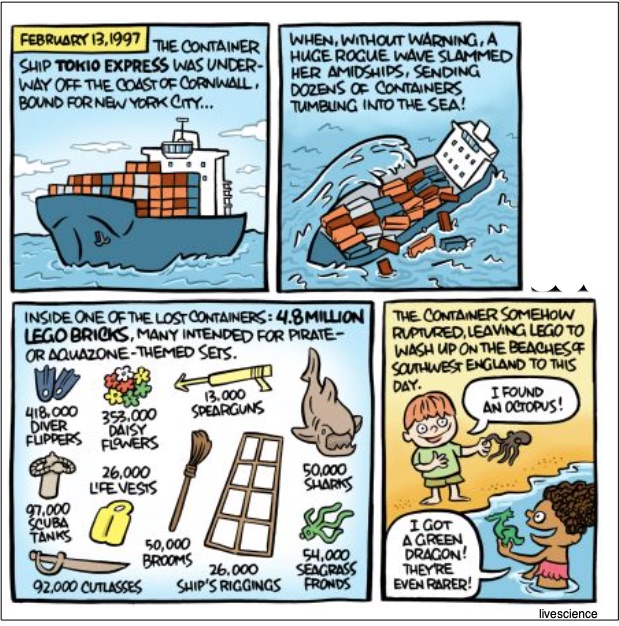

It was called The Great Lego Spill.

On February 13, 1997, a whopping 4,756,940 Lego (plural has no s) slid off a ship heading for New York from the Netherlands. This excerpt from a longer cartoon told the story:

The Lego were in one of the 62 errant containers that were nudged overboard by a giant wave. (Can you imagine seeing it happen?) Since then, Lego parts have washed onto beaches near England’s southwestern tip.

Like these 240 flippers, many had a sea-theme:

Container Ships

Our story starts in 1950. At a typical port, flour or clothing or raw cotton was packed in barrels, bags, or crates. Their next destination was a loading dock or a local warehouse.

Labor intensive, longshoreman did all of this loading and unloading. It probably resembled the following mage:

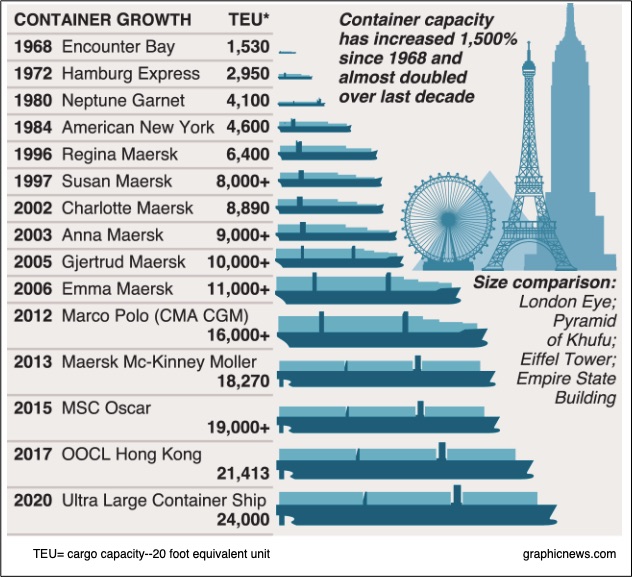

The turning point was 1956 when a North Carolina trucker rigged an oil tanker with 58 trailer trucks. Using only the containers, they eliminated the need to individually move countless commodities. Instead, they moved only the box.

You see the difference. Whereas moving your cargo 1,000 feet took hours, instead it took moments. Cost plunged from $5.83 to less than 16 cents a ton as did pilferage, damage and the number of longshoremen.

Once they started stacking containers in vessels, capacity soared:

Our Bottom Line: Externalities

Defined as the impact on an unrelated third party, an externality can be positive or negative. Because of scale, container ship externalities are countless. The largest cargo ships can carry 20,000 containers. That means one quarter billion containers annually travel among our ports. The upside includes minimal transport expense, easy transfer from boat to train and truck. But among the negative externalities, we can list the size of a catastrophe. With Lego, the plastics environmental devastation was cataclysmic. Combining the pandemic and these huge vessels led to magnified supply chain snarls and port pile ups. The good and the bad are bound to be big. Inevitably, we get a Great Lego Spill.

My sources and more: For two great articles on the Lego spill, I recommend The New Yorker and Smithsonian. Then, my souce for container ship history was a past econlife post. And finally, you might enjoy, as did I, this video’s story of building a 100,000-Lego-piece container ship.