What do you get when you combine Ingvar Kamprad, Elmtaryd, and Agunnaryd? It’s IKEA, an acronym that combines the names of the founder, his farm, and his village.

Since IKEA began as a mail order business in 1943, it’s been using some clever selling strategies. Actually though, it’s all about demand.

IKEA’s Selling Strategies

The IKEA store layout breaks all of the rules. Rather than a grid or racetrack design, it leads customers through a one-way path that forces us to see toilet brushes, cookware, and lamps on the way to the chair we are there for. Different on every floor, the compelling and sometimes confusing layout creates the Gruen effect, a phenomenon that results in impulse buying because you lose track of why you came in the first place. (Victor Gruen, designer of the first shopping centers, used design to encourage extra mall purchases.)

IKEA’s tactics range from mirrors that give us a sense of belonging when we see ourselves in a room to decoys that make other items look attractive because they are not. But most of all, they use low prices that are supposed to keep going down. Researchers that studied 16 years of their catalogues followed the price trajectory of the Poäng chair. In 1994 it was priced at $179. Now it’s could cost as little as $129. Fivethirtyeight called it the survival of the fittest catalogue.

Now we know the name of this ubiquitous chair. (I didn’t.):

The chair’s plunging prices:

Even self-assembly has a plus. In a 2011 study, (that we described at econlife) participants gave a higher value to items they made themselves. The researchers, including economist Dan Ariely, called it the IKEA Effect.

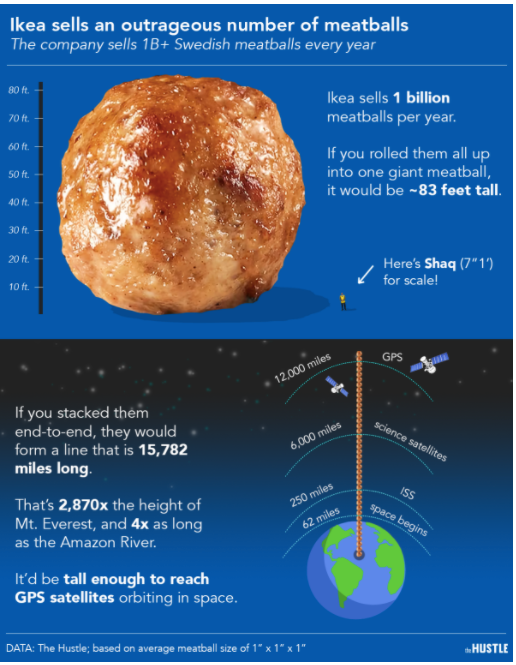

But really, it all can take us back to the meatballs they sell. IKEA found that people spend more when they are not hungry. The results of one study indicated that shoppers spent two times more on furniture after they ate. In addition, IKEA sells a lot of meatballs–maybe more than one billion a year:

Our Bottom Line: Demand Determinants

IKEA knows demand.

Most crucially, they realize that the law of demand says we buy more when price drops and less if it rises. Through Poäng chairs, the law of demand lives.

Also though, they understand demand. As our willingness and ability to buy goods and services at different prices, demand is defined as a series of price quantity pairs rather than just one. Our demand for a cup of coffee could be 1 if price is $2, 2 if price is $1.50, and 3 if price went down to $1. Economists call those three price quantity pairs our demand for coffee. IKEA’s retail strategy is designed to increase our demand by focusing on two determinants that nudge demand up and down. They are very aware that utility and complementary products are demand determinants that can influence how much we buy.

Mostly though, they understand the meaning of a meatball, and how it can encourage us to buy a bed.

My sources and more: Thanks to my Hustle email for alerting me to IKEA’s strategies. From there, this website and fivethirtyeight had more facts about IKEA. Then, for more, you could return to our econlife post on Victor Gruen and our discussion of the IKEA effect. Please note also that our featured image is from the NY Times.