Can Economists See the Hot Hand?

January 21, 2015

The Eurozone Sunk Cost Problem

January 23, 2015The decisions we make about bread machines, surgery and gasoline can be remarkably similar.

Where are we going? To the influence of a frame.

But first…

Bread Machines

Maybe 20 years ago, when bread machines were first introduced, one retailer started with a single model priced at $120. Faced with sparse sales, they increased interest by adding a second $80 machine.

What happens next though is what gets the behavioral economists really excited. The retailer placed a $475 machine on the shelf and the $120 model sold like hotcakes.

Surgery

In an experiment at Harvard by psychologist Amos Tversky, physicians were given one of two statements about the success of a surgical procedure. Asked if they should operate, the majority of respondents said yes to the first statement. Both though are the same:

- The one-month survival rate is 90 percent.

- There is a 10 percent mortality in the first month.

and finally…

Gasoline

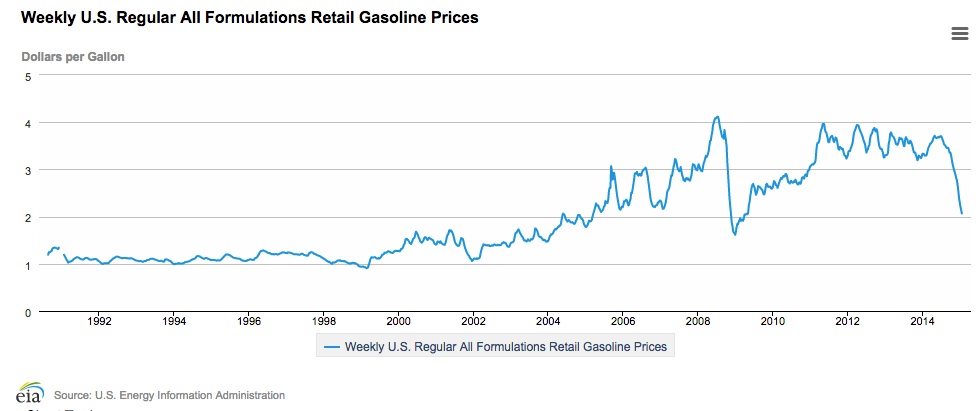

Asked if $3.00 a gallon gas makes you happy, you probably would say no. But why then, a year ago, would you have been pleased? The following graph has the clue:

Frames

For bread machines, surgery and gasoline, our attitudes are shaped by a reference point that behavioral economists call a frame. With the bread machines, the $425 machine signaled that $120 was a good price. For surgery, when the frame was a positive statement, the response was positive. For gasoline, the direction in which prices moved created the frame. Moving downward from $4.00, $3.00 looks good but not when price rises from $2.00.

Our Bottom Line: Competition

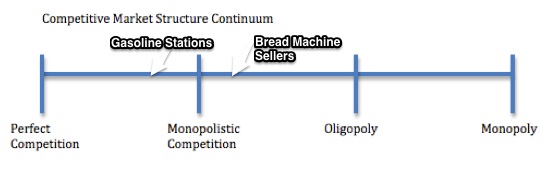

In traditional economic texts, price making power increases as you move across the following continuum:

To enhance their price making power, firms have been able to influence consumers with frames. Now though, with Amazon and the potential for other online price comparisons, I wonder if the power to frame has diminished or at least changed.

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)