The U.S. deficit just touched $1 trillion. Taking 11 months of the October 1st to September 30th fiscal year to get there, federal spending minus revenue has not been this high since 2012.

There are several ways to look at the deficit. So let’s give it a try.

The Size

Sometimes the real size of a big number is tough to grasp. When people create a zero to one billion scale, close to half of them misplace the million mark. (Hint: 500 million is halfway.) And one trillion is one thousand billion in the U.S. (It’s one million times one billion in the U.K.).

The big numbers make it easy to misunderstand why the deficit is so tough to shrink.

Spending

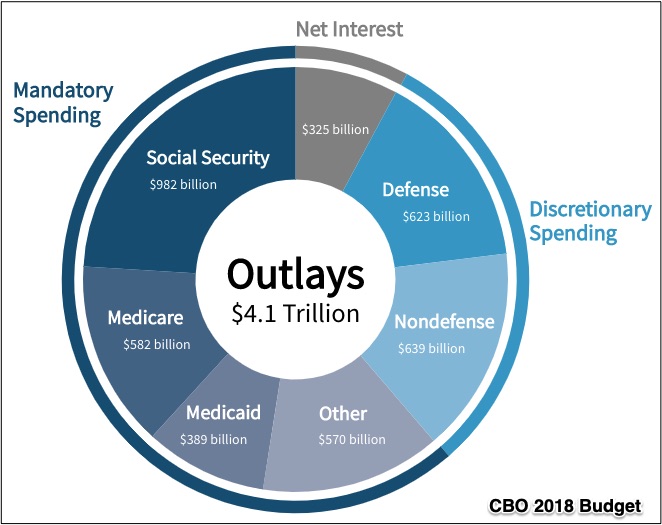

Since government spending is up 7 percent to $4.1 trillion, maybe we just spend less. But there we have a problem. The numbers we can cut sound big. But they are just billions in a trillion dollar budget.

Small Spending

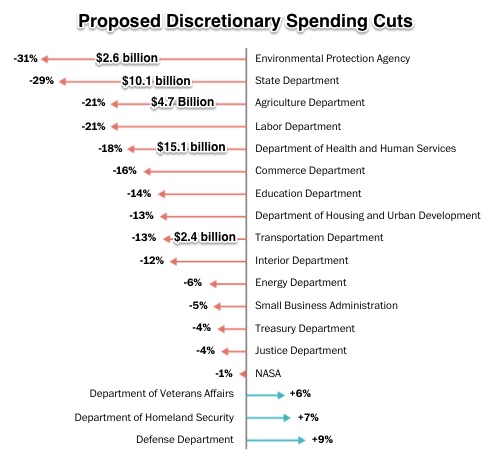

In his 2018 budget, President Trump proposed reducing more than one dozen areas. However, you can see that, at several billion, a big slice of one department’s budget is a tiny sliver of $1 trillion:

Big Spending

The big spending comes from entitlements, defense, and the interest on the debt. Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are the big chunks of entitlement spending that are called mandatory because the law requires them. We also have to pay the interest that is due on all that we borrow. Add defense to that and you get mighty close to the $4.1 trillion in government spending. The other parts of the budget–the discretionary expenditures that amount to several billion here and several there–are relatively tiny.

You can see that the non-defense discretionary slice of the budget pie is approximately 30 percent of the whole:

Borrowing

Because of rising deficits and insufficient tax revenue to cover it all, the government has to borrow more. So as a last step, we can look at the debt.

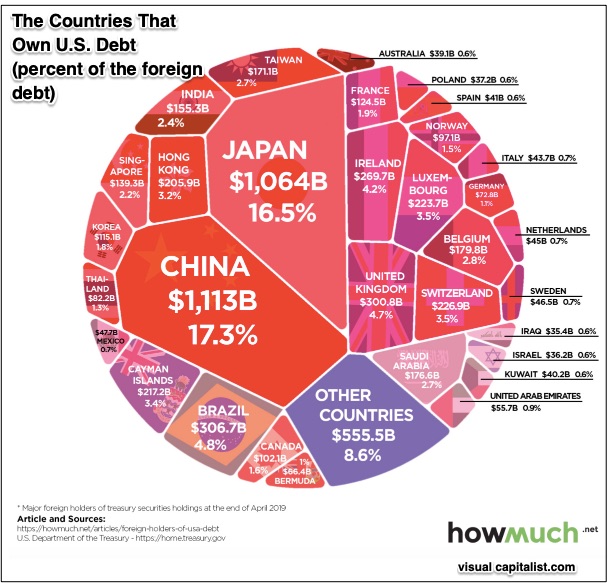

Rather than go to a bank to get a loan, governments borrow with bonds. You and I, businesses (including banks, mutual funds, and other investors), and governments (including the U.S., state, and local governments) can buy U.S. bonds. When individuals, businesses, and foreign governments buy the bonds, the U.S. government gets the money until it has to pay it back. Most of us buy bonds because of interest payments we get in return. I have oversimplified somewhat but this is the basic picture.

Last July, the foreign debt holdings were 28.5% of the total that the U.S. owed. And yes, China was #1 in the foreign government list:

Our Bottom Line: The Tragedy of the Commons

Called the tragedy of the commons, fisheries are depleted, work refrigerators are messy, and the air is polluted when commonly held resources are overused by individuals pursuing their own self-interest. Perhaps the burgeoning U.S. deficit is a version of the tragedy of the commons.

Economic legend John Maynard Keynes told us that “The boom, not the slump, is the right time for austerity at the Treasury.” But we’ve not taken advantage of the boom. One reason could be the tragedy of the commons.

My sources and more: Only a beginning, this Brookings report and WSJ provide the overview. Then, to see when budget deficits are supposed to shrink and when they balloon, Fivethirtyeight is ideal. Finally, visualcapitalist and the CBO had the perfect graphic summary of the U.S. debt.

Please note that several of today’s sentences were in a past econlife post.