How Marijuana Taxes Affect Our Behavior

August 14, 2017

New Territory for Self-Driving Cars

August 16, 2017Seven years ago, the Philadelphia City Council voted against a sugary drinks tax while last year, they approved it. The difference was the approach. It had not worked to cite the health benefits so instead they focused on the revenue the tax would generate.

The problem now though is deciding whether the tax has been a success. As with all sugary drink taxes, there were unintended consequences.

The Philadelphia Tax

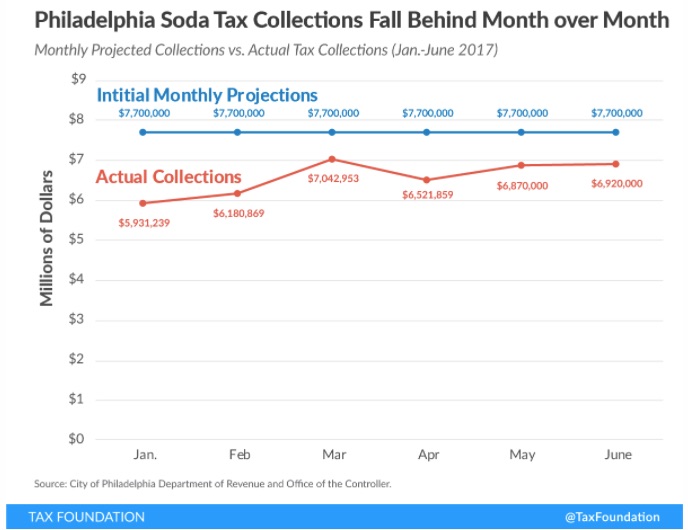

The Philadelphia tax on sugary drinks and diet soda kicked in on January 1, 2017. As a 1.5 cents an ounce tax on distributors, it was supposed to fund pre-K education. To date, it has not produced as much as they expected.

The projected amount was $7.7 million a month. Ranging from $5.9 million to $7.04 million, the revenue shortfall has been consistent:

Advocates

Advocates of sin taxes like the Philadelphia levy sound like economists. Citing the law of demand, they remind us that a higher price diminishes the quantity demanded for unhealthy food and drink. Then, they say the revenue from the tax could be used productively for education. And finally, they note how the tax is easy to collect.

Opponents

Opponents point out that that the impact on the quantity demanded is debatable. At first people buy less. However then they appear to acclimate and consumption moves closer to pre-tax levels. Substitution is also a concern. When one municipality levies a tax, people drive to nearby localities that do not have it. In addition, the “Coke to Coors” effect could set in whereby people substitute beer for soda.

After six months of the Philadelphia tax, we appear to have had more of the negatives. They are…

- The city is not getting the projected revenue

- People have the incentive to drink more beer because it is relatively cheaper.

- Affecting somewhere between 120 and 160 positions, Coke and Pepsi have eliminated local jobs.

A Santa Fe Soda Tax

Last May, Santa Fe’s voters rejected a two cents an ounce soda tax. With more people showing up at the polls than for the mayoral contest, affluent neighborhoods were evenly split. However, a majority voted no in predominantly lower income areas.

The reason could relate to regressive taxation.

Our Bottom Line: Regressive Taxation

When people with less pay a higher proportion of what they earn than those with more, the tax is regressive.

Assume two people owe a $10 soda tax when they buy the same amount of Coca-Cola. Assume also that the first individual earns $100 a week and the second one, $200. That means the less affluent person has a tax rate of 10% while the other’s is 5%. It also means the tax is regressive.

Because the Philadelphia sugary drinks tax is regressive, it has been called unfair.

My sources and more: For more facts on the Philadelphia tax, this Tax Foundation article is a (biased) possibility. However, I especially found “From Coke to Coors” an interesting paper. Also in the interesting column, this New Yorker article was good on the origin of the Philadelphia tax as was WSJ on the Santa Fe tax. Finally, at econlife, we have also looked at successful soda taxes.

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)