Why Times Should Change

March 10, 2019

How Venezuela Caught an Incurable Case of Dutch Disease

March 12, 2019Elon Musk was delighted that Norway will be banning new fuel-run cars in 2025:

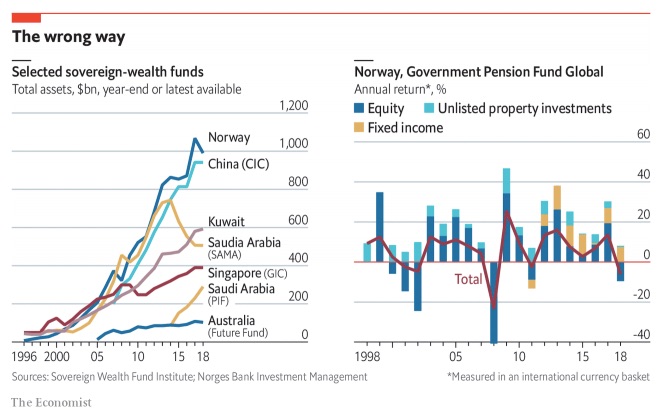

Norway also announced that its trillion dollar sovereign wealth fund would divest its oil and gas exploration and production investments. As they explained, the purpose is diversification.

For a country with so much oil wealth, Norway’s decisions could sound illogical.

Not necessarily.

Norway’s Oil Story

The year was 1968. The place was Oslo. Farouk al-Kasim had six hours at the railway station until his train arrived. In the process of moving to Norway from Iraq, he was an unemployed oil executive. So he decided to walk to the Ministry of Industry for the names of oil companies in Norway.

When Norwegian officials heard his academic and corporate credentials, they asked him to return that afternoon. Kasim quickly realized that Norway had no one to interpret the reams of data they were getting from private companies searching for oil. Soon he had a job.

And Norway had a windfall.

After years of unsuccessfully looking for oil, Norway discovered that it controlled massive reserves. Kasim was deployed immediately. His recommendations would include how to maximize and spend revenue. He had to figure out a balance between private initiative and government oversight.

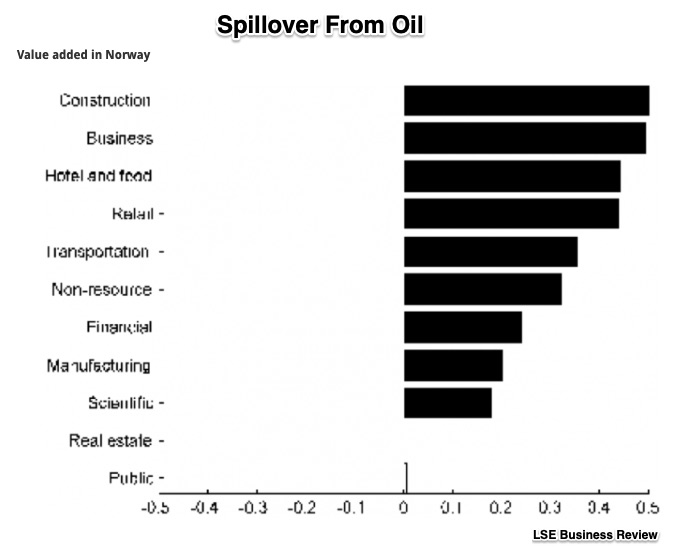

The bonanza could have been catastrophic. When countries focus all of their land, labor and capital in one area, other industries suffer. But Kasim encouraged technological research that achieved 45% extraction–20% more than the average. Norway also was able to use the technology beyond the oil fields. Its spillover helped related industries to develop and grow:

On the spending side, the Norwegian government eventually exhibited considerable discipline. Here, I like to think of Odysseus. Tied to the mast, he could resist the Sirens’ song. Somewhat similarly, Norway limited what it could spend. It said 4% of a normal return was the max it could directly receive. Otherwise oil revenue had to expand domestic production. And when it grew too large for that, they said it had to be used outside the country.

The result? Norway limited its dependence on oil. Yes, it would suffer when oil prices plunged. But still, the country had a buffer.

Below, you can see how the fund invests and compares to others:

Still, oil is a hefty part of Norway’s economy:

Our Bottom Line: Dutch Disease

The oil industry reminds us what a commodity boom can do to an economy when it employs the best land, labor, and capital. As it blossoms, other industries wilt. At home it’s tough for non-oil businesses to pay for increasingly expensive resources. Abroad, a nation’s currency appreciates when international markets clamor for the new commodity. The problems start because that stronger currency makes other exports less attractive.

Then, it gets even worse when other industries disappear and government depends on oil revenue for social welfare spending. When the boom turns to bust, there are no replacement industries to fill the void, government money dries up and the source of consumer spending and incomes contracts. It happened in the Netherlands during the 1960s and ’70s (hence the name Dutch Disease). At this point we can call a windfall a curse.

But not for Norway.

My sources and more: If you read one extra article, do look at what FT columnist Martin Sandbu says about Farouk al-Kasim. From there, the possibilities include this LSE summary of a Norges Bank study and this paper on the origins of Norways’s sovereign wealth fund. Also, Norsk Petroleum had more details on oil revenue.

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)