The Top Ten Worst Reasons For Not Having Women on Corporate Boards

June 12, 2018

The FDA’s Label Problem

June 14, 2018During the 1980s, North Korea was making radios and TVs. But unlike its South Korean neighbors, manufacturers could not export them. Pre-tuned to a specific frequency, the equipment would only broadcast government propaganda when you flipped the on-switch.

Pre-tuned is the word to remember when we look at North Korea’s economic statistics. Because releasing national account numbers is illegal, researchers instead gather what one economist called “mirror information.” They collect data from businesses in South Korea and China that deal with North Korea. They speak with defectors. And they guess.

So, knowing the data could be inaccurate, let’s see what we can figure out.

The Past

Post World War II

After World War II, the area of the Korean Peninsula that was occupied by Russia became the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. When they left, the Soviet connection remained. The economy was centrally planned and boosted by Russian aid.

1980s-1990s

But when the Soviet Bloc started to dissolve, so too did the oil the North imported. Unable to produce enough fertilizer and electrically powered irrigation, the country’s resources contracted. Add floods to the equation and you get a massive famine. The government even engaged in a “Let’s eat two-meals-a-day campaign.” And then, their nuclear arsenal had to have drained even more resources.

On the plus side, the famine shifted some of the country’s economy to private businesses. Rather than state-owned enterprises (SOEs) foreign aid flowed to black markets. Sold by the elite, that aid directed wealth and loyalty to a market instead of state run institutions. We could say that the failure of the government led to a pseudo market sector of the economy.

Now

While North Korea remains a planned economy, market activity is increasing. As some observers have hypothesized, the central government is exerting less control by giving the SOEs some autonomy to form joint ventures and engage in trade. They also point out that economic activity disproportionately depends on counterfeiting, cybercrime, and illicit or illegal ways of earning revenue.

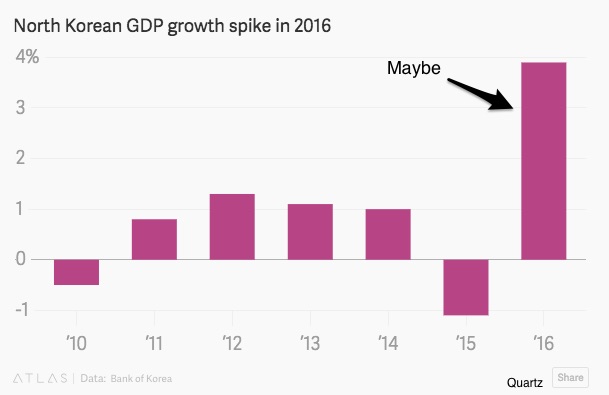

The result could be some economic growth. I’ve added the arrow and the maybe:

Our Bottom Line: The Price System

Here is where the price system comes in handy. As long as there are markets in North Korea–even if they are distorted and disparate–we can get information from the prices they generate.

Below you can see the prices in rice markets. Because they are somewhat consistent, North Korea observers conclude that sanctions and a drop in commodity prices have not created famine conditions.

I’ve drawn the arrow and written the note to show how prices respond to international tension:

At this point, we have to return to where we began. Because anecdotal prices cannot offset a “pre-tuned” flow of data (and an unlit North Korea in our featured image), the North Korean economy remains a mystery.

My sources and more: Once I started to look, my sources on North Korea multiplied. The best though was this Peterson Institute podcast that I enjoyed during one of my four mile walks. Also, you might enjoy this article from PRI and this one from Global News. However, for the best contemporary information, I suggest the 38north.org blog. (I did use a Quartz graph but was disappointed that they expressed insufficient skepticism.)

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)