Airline Pricing Mysteries

July 21, 2015

Exposing What You Hide in Your Garbage

July 23, 2015I’ve been reading Eating People is Wrong. Mostly about famine, the book first looks at when and why hunger drives people to eat each other.

Where are we going? To how a crop shortfall might not cause a famine.

Starvation at Sea

Faced with a disabled ship, the crew of the whaling vessel Essex divided themselves among three whaleboats. The debate on where to go initially focused on the Marquesas. However, “the men had heard that the islanders found human flesh so delicious ‘that those who have once eaten it can with difficulty abstain from it.'” As a result, hoping to land in Peru or Chile after 60 days, they headed south.

With little food that had to last for two months, their daily ration could be no more than six ounces of dried bread called hardtack and a half pint of water. Once the two months passed and their destination remained a distant hope, the tougher decisions began when a shipmate died. Deciding to consume his body, they probably got 30 pounds of meat because he had been starving instead of the average 66 pounds that a human provided. As for the experience of eating after such deprivation, they only got hungrier when they ate more.

Eating People is Wrong briefly alludes to the crew of the whaling vessel Essex in a list of cannibalism examples. Showing how people can be driven to such extreme behavior, the book also takes the reader to famines in which victims have engaged in survivor cannibalism (where the person is already dead) and murder cannibalism (in which the person is killed and then ingested). What we really learn though is the path along which starvation can lead us.

Famines

A life threatening food emergency is the common denominator that the Essex crew shares with famines that have struck people for millennia. Famines are also characterized by extreme hunger, high food prices, migration, and starvation deaths. We cannot say though that all famines have the same cause. Sometimes a famine begins with a crop shortfall. Then though the real food emergency starts with wartime priorities that distort food distribution, hoarding, prices with problematic incentives or government’s counterproductive allocation of resources.

A list of famines would include the following:

- Sancerre: 1572-73

- Soviet Union: 1931-33

- Ireland: the late 1840s

- Great Bengal Famine: 1943-44

- Chinese Great Leap Famine: 1959-61

- North Korea: mid-1990s

- Somalia: 2011-2012

Our Bottom Line: Production and Distribution

Whether looking at shipwrecked starving sailors or Ireland’s potato famine, we are really seeing decisions about scarcity. Defined by economists as limited quantities, scarcity is the reason we have economics. To solve the economic problem of scarcity, societies have created economic systems that dictate what to produce, how to produce, and who receives the income.

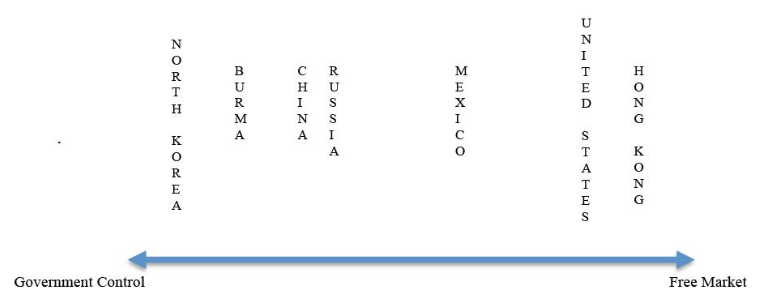

Imagining those economic systems, we can picture a continuum with the market at one end and a government dominated centrally planned economy at the other extreme.

Focusing on the market side of the economic spectrum, Adam Smith tells us that markets minimize the damages from crop shortfalls because price differences encourage interregional distribution while higher prices from shortages stimulate more supply. By contrast, Nobel Prize winning economist Amartya Sen focused on distribution. Saying there was enough food in Bengal in 1943, he looks at the role of government.

So can a hungry country have food? It all depends on how a crop shortfall is managed.

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)