What Can We Learn From Japan?

April 27, 2021

Judging the Spillover From Corporate Tax Avoidance

April 29, 2021Strolling near a top corporate executive suite, you are more likely to bump into a man named James or Michael than a woman. At a combined total of 40, there are nine more James and Michael S&P 500 CEOs than the 31 females in a similar position. Correspondingly, among S&P 500 board chairs, 21 are women and 23 are named John.

Where are we going? To an expectations bias.

The Workplace Gender Gap

Globally

In its global Glass Ceiling Index, The Economist places the U.S. at #18 while as always, the Nordic nations fared best for female empowerment. Although our share of women in management and on corporate boards (though paltry) boosted our rank, parental leave and political representation were the criteria that tugged the U.S. downward.

You can see that Japan and South Korea were far behind Sweden and Iceland:

The U.S.

In a recent report, Equileap (a gender equality data firm) used 19 criteria to assess the gender gap among S&P 500 companies. First, they grouped their 19 criteria into five categories that started with leadership and workforce numbers. Next, they focused on compensation and work life balance and then, promotion policies and transparency. At the end, in the fifth group, they cited the “gender controversies” that took companies to court.

In their top 25, General Motors led the list, followed by Nielsen and Kellogg’s:

But still, the S&P 500 company gender gap remains massive:

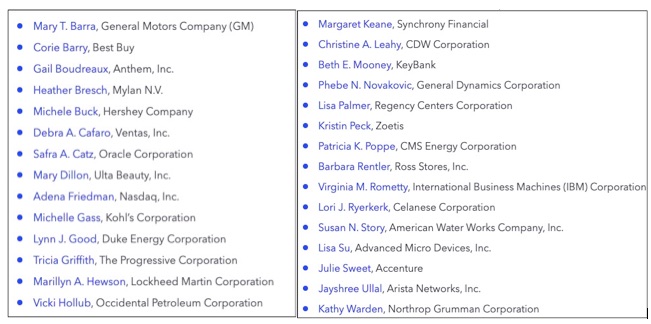

These are the female CEOs in the S&P 500. Up-to-date from Catalyst, it names the 30 S&P 500 female CEOs as of January 2021:

Asking why the numbers are small, WSJ had some answers. They explain that more women need to occupy a “rainmaker” position. The people who bring money into a firm tend to move to the top. They come from sales, successful divisions, operations. Women instead lead Human Resources, legal departments, administration.

Displaying the gender of the individuals whose roles lead to the top, the purple dots show the females and the yellows, the men:

Also, below, you can see the executive positions with the most purple dots usually are not in the pipeline to the top:

Our Bottom Line: Expectations Bias

At this point, a behavioral economist could suggest that we have a self-fulfilling prophecy. Having fewer women at the top makes us expect fewer women at the top. We can call it an expectations bias:

And that returns us to what James, Michael, and John tell us about the workplace gender gap..

My sources and more: Through a link to this report, MarketWatch reminded me it was time to look again at female CEOs. From there, The Economist is always a handy source for more data as was WSJ and Equileap. (Several sentences from today were in a previous econlife post.)

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)