How An Elite College Determines Your Future

April 17, 2019

What Misery Indexes Say About Baseball and the World

April 19, 2019#TBT: Our Throwback Thursday looks back at Standard Oil and then ahead to Amazon. We ask how they could possibly be similar.

The Standard Oil Case

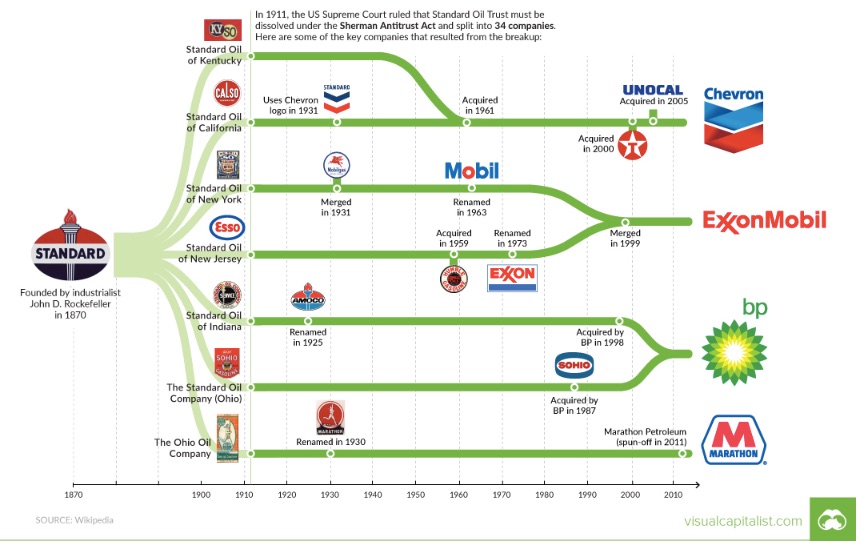

On May 15, 1911, the Supreme Court divided a gargantuan oil trust into 34 smaller companies that actually were very large businesses. They included Standard Oil of New Jersey, Standard Oil of New York, Standard Oil of California, Standard Oil of Ohio, and Standard Oil of Indiana. Now we know some of them as Chevron, ExxonMobile, and Marathon:

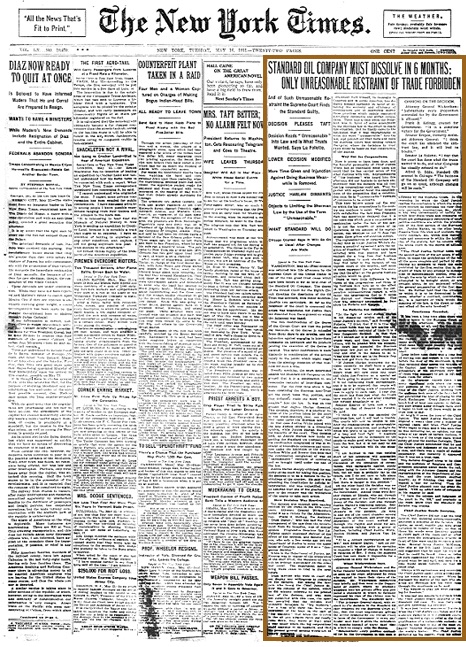

The Supreme Court explained that Standard Oil was violating the 1890 Sherman Antitrust Act by acting “in restraint of trade.” In the NY Times, the story was huge:

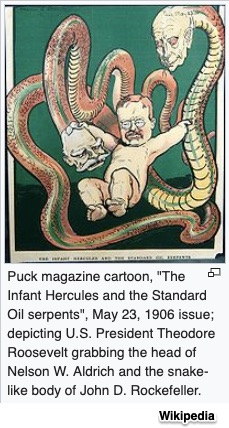

John D. Rockefeller

With a net worth of $27 million in 1887, $324 million in 1913, and close to $1 billion at its height, John D. Rockefeller died when he was 97 years old in 1937.

Below, John D. Rockefeller is approximately 60 years old. The artist was Oscar White.

His story begins with some rather unorthodox child-rearing practices. John D.’s father reputed said, “I cheat my boys every chance I get, I want to make ’em sharp .. .” Meanwhile, his mother, a determined disciplinarian who felt bound to “uphold the standard of the family,” continued a thrashing even when she concluded that John was innocent, saying, “Never mind, we have started in on this whipping and it will do for the next time.”

Considerable discipline, minimal schooling, and hard work for nearby farmers seem to characterize Rockefeller’s childhood in western New York and then in Cleveland. Although a day of hoeing potatoes brought him only thirty-seven cents, he soon accumulated $50, which he is said to have loaned to the farmer for whom he worked. Commenting on his early business ventures, he said, “I soon learned that I could get as much interest for $50 loaned at seven percent… as I could earn by digging potatoes for ten days.”

As a high school student, the study of bookkeeping “delighted” him and led to his first position at sixteen as a bookkeeper with a local merchant. Accumulating $800 in savings in only three years (having earned $15 a month at first and later $50), he soon became a merchant himself.

Standard Oil

Standard Oil began with what we now would call some venture capital. A Mr. Andrews approached John D. for money to build an oil refinery. While at first Rockefeller and his partner contributed $5,000, soon John D. left his produce business, bought out his partner, and devoted himself exclusively to oil. He accurately saw that the demand for oil would skyrocket. At first one of thirty, he soon became the largest oil refiner in the Cleveland area, owning a network of warehouses and tank cars, and displaying a penchant for bargaining with railroads for rebates that gave him a price advantage above all others. By 1870 he had incorporated as the Standard Oil Company of Ohio, destined soon to quash all competition and control the entire industry.

One source of Mr. Rockefeller’s success was his vertical integration. Vertical integration works like a ladder. As a vertically integrated firm, Standard Oil controlled virtually every step of the productive process. It had the wells (the first rung), the pipelines (a second rung), the barrel makers, the refineries, and the retail outlets (the top of the ladder).

So yes, Rockefeller was an extraordinary businessman. But also, he made secret deals with railroads where his rates seemed equal to everyone else’s. Actually, the railroads were giving him secret rebates and also paying him when they did business with other oil companies. Competitors seemed eager for him to buy them out. But really, he threatened to lower his prices until he put them out of business if they refused.

When we combine his acumen with his tactics, we wind up with a gargantuan business called a trust. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Trust dominated most of the industries in which it competed. For oil production, it could claim more than 90% control.

Our Bottom Line: Amazon

Our Bottom Line: Amazon

On the surface Amazon is very different from Standard Oil. Through low prices, fast shipping, great movies, one click ordering (you know it all), it enhances consumer welfare. So why the antitrust?

Let’s look at it this way.

According to a Yale Law Journal paper, Amazon is the platform that sells its more than 120 of own products and countless others. For those Amazon products, it competes against the firms that use its platform. Reflecting its conflict of interest, Amazon owns the platform that sells its private label, has competitors selling the same items, and then also decides search rankings. Firms flock to Amazon because platforms reduce their cost of entry.

Then, as former law student Lina Khan further details, Amazon is a retailer and a marketing platform. It delivers packages through a logistics network, it is a payment service, a credit lender, a book publisher. It produces TV shows and films, manufactures hardware, and is a leading host of cloud server space.

Khan suggests that more recent definitions of anti-competitive behavior need updating. Although Amazon ostensibly augments consumer welfare, its behavior could be considered anti-competitive. Her concern focuses on its conflicts of interest. She cites the power that interconnected distinct lines of business create. And finally, she asks if the “structure of the market incentivizes and permits predatory conduct.”

Does it sound a bit like Standard Oil? (The 20th century comparison intrigues me.)

My sources and more: With a bit of editing, the Standard Ol story is an excerpt from my book, Econ 101 1/2 (then Avon books–now Harper Collins). But I was inspired by the synergy between this WSJ article and a Planet Money antitrust series. The series led me to this Yale Law Review article–“Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox” –and the Visual Capitalist.

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)