The Food Fights Between the U.S. and China

April 15, 2018

Deciding Whether to Tax the Internet

April 17, 2018Pension problems were in the news yesterday.

A NY Times headline said “…States in Pinch of Own Making.” That pinch referred to exceedingly high pension obligations that require cutbacks elsewhere. One example was Klamath Falls, Oregon, a city of 21,000 whose biennial pension increases of $600,000 meant street and bridge repair cutbacks.

One way to consider pension bills is through a generational lens. Referring to economist Tim Harford’s recent FT column, let’s figure out which age cohort deserves the most.

Age (Re)Distribution

To start, Harford takes us through some alternatives. He reminds us that the U.S. redistributes tax dollars to the aged through Medicare. Similarly, other countries have pension programs or, like the UK, waive national health insurance payments after a certain age. Alternatively, money can move from the old to the young through free college tuition. Even interest rate policy can favor savers (the aged) or borrowers (the young).

More broadly, Harford suggests that the young should fund the old because they will benefit from an increasingly affluent society. Or, perhaps because the old earn more than the young, they should subsidize everyone else. A third possibility? Forget money. Instead capture variables that exist beyond markets through SWB (self-reported wellbeing).

In a new paper, Nobel Laureate Angus Deaton ponders life cycle changes in SWB as a possible basis for redistribution. Saying the young, the middle-aged, and the elderly can have competing interests, he asks how government policies should respond. His data source is a Gallup questionnaire in which participants are asked their current rung on a ladder numbered 0-10 of the best and worst possible life, and where they expect to be in five years.

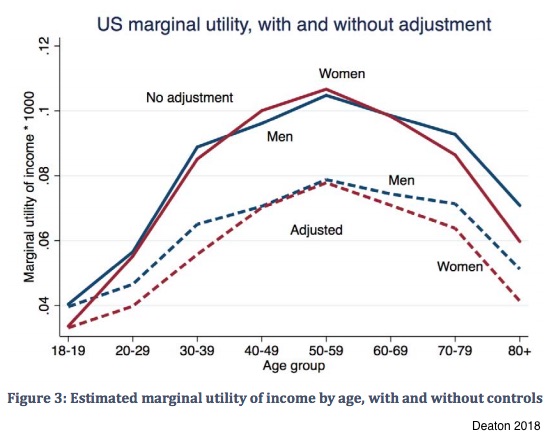

Deaton explains that we could base redistribution decisions on income or welfare. Using income, we typically select the elderly or young adults. However, policies change when welfare based on SWB enters our analysis. Then we wind up with middle-aged men. Defined as the extra value we would get from more income, the marginal utility of these men is greatest. Furthermore, seeing their dip in SWB, perhaps they deserve the highest transfer from the rest of us.

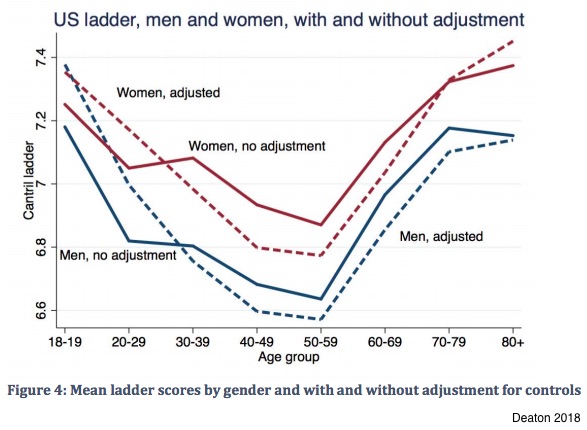

Men aged 40-59 display a dip in SWB:

And yet their income has greater marginal utility–usefulness–to offer:

From here we have Dr. Deaton saying he is really just hypothesizing and his reasoning generates more questions than answers. However, if we want to bring welfare considerations back to economics like some of the 19th century economic thinkers, then we best broaden our vistas to SWB.

Our Bottom Line: Opportunity Cost

As economists, we have to remember opportunity cost when we consider the redistribution policies that collect taxes from one group and disseminate them to another cohort through government programs. Since all land, labor and capital is limited, we have to make tradeoffs about who gets what. Economists summarize it all as the problem of scarcity.

One way to perceive the tradeoffs that scarcity necessitates is through a generational lens. If government decides that young should get more, then the old and the middle get less…or maybe the opposite.

For now, Klamath Falls, Oregon has made its decision while Angus Deaton might say we have lots more to consider.

My sources and more: Among all of the good ideas I have gotten from Tim Harford, today’s post reflects one of them. I also recommend taking a look at this paper from Angus Deaton.

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)