Where Living Longer Is Changing Lives

September 30, 2021

Learn With Elaine: McDonald’s Speedy Drive-Thru

October 1, 2021It makes sense that when we take Uber or Lyft, we reduce traffic congestion and CO2 emissions. Because we are driving less, ride sourcing means fewer cars and more public transit. Yes?

Not necessarily.

Ride Sourcing Problems

Transportation Network Companies (TNCs) like Uber and Lyft add to congestion. In a six-year San Francisco pre-pandemic study, weekday delay hours were up 62 percent when compared to a 22 percent counterfactual without TNCs.

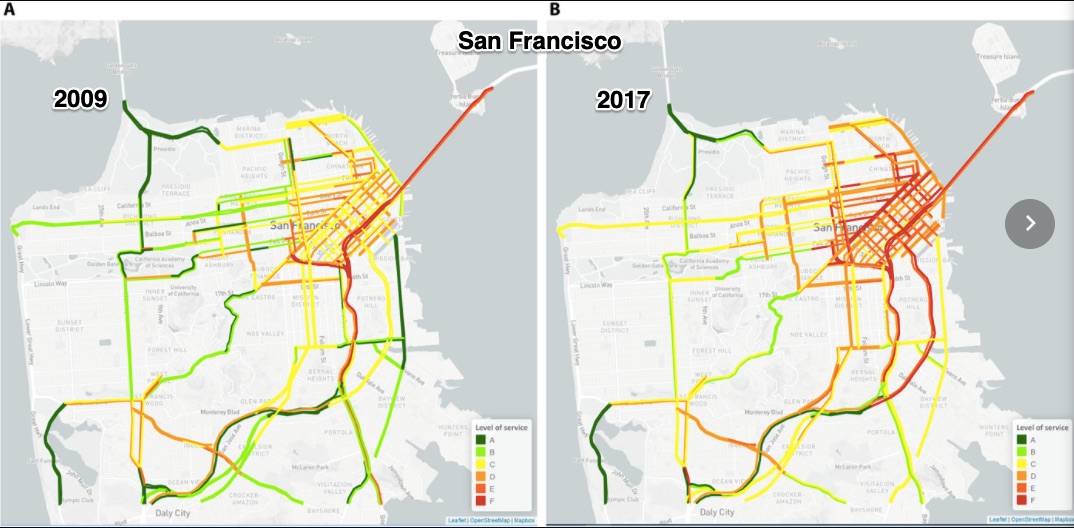

Below we have before and after maps showing peak delays in red and less with yellow and green. Although the dates also correspond to a population and employment increase, researchers believe that there was a causal connection between ride sourcing and traffic congestion:

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.aau2670

On the plus side, researchers concluded that emissions shrink because fewer fuel combustion engines are starting. (Warm engines emit less than cold ones.) Also, more environmentally friendly, TNC vehicles tend to be newer.

But the downside is steep. One reason is substitution. If riders replace a walk or a bike with ride sourcing, they add to congestion. Even a fully electrified fleet creates an extra ride-hailing cost. Meanwhile, on the driver side, we have deadheading. Describing out-of-service travel, deadheading is close to 50 percent of vehicle miles traveled (VMT) by ride sourcing drivers in NYC and 20 percent in San Francisco. Adding immense extra mileage, accidents, emissions, and noise, deadheading creates the need for an offset that reduces mileage.

Ridesharing Solutions

In a new study, a group of engineers suggest we need to encourage pooling. While they do not tell us precisely how, they do describe rider characteristics and calculate that TNCs cost us an extra 35 cents per trip more than a private car. From there, knowing the need, policy planners should be able to figure out the incentives that will nudge us into pools.

Since Uber’s ride shares were at 20 percent and Lyft’s were 40 percent of all rides (2017), both have considerable room to improve. To determine who can be urged to pool, in the 2021 paper, we are given detailed profiles of typical riders. The group to incentivize includes heavy low income TNC users and younger users. As a result, if an individual is heading to mass transit, they could respond to a promotional pooling discount that takes them there. The goal could also be to shift waiting time to walking time and reduce deadheading.

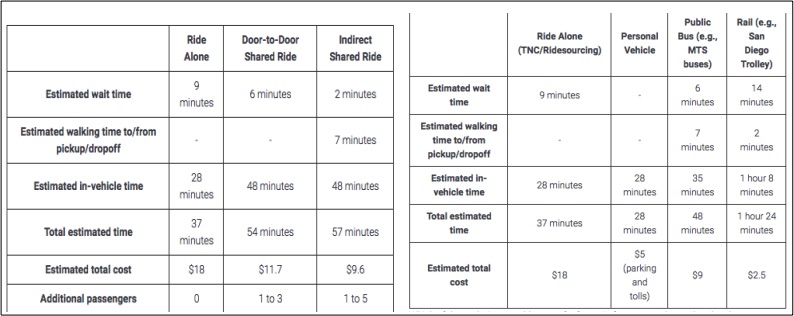

Told they were going to a restaurant or a bar, survey participants were asked to select a transport alternative:

https://escholarship.org/content/qt44q6n0mm/qt44q6n0mm.pdf

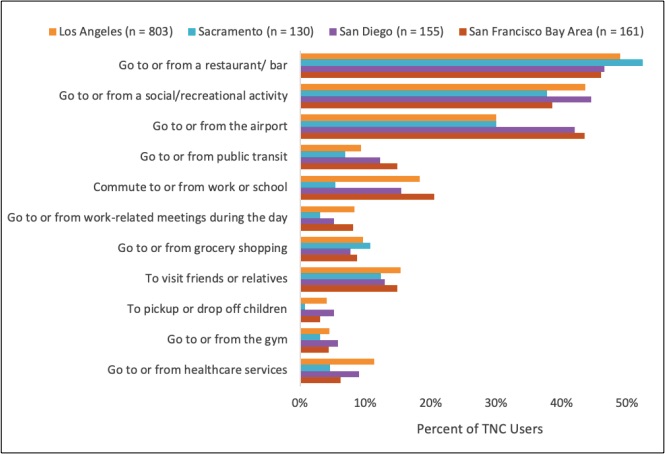

But they also could have been going to work or home, to a supermarket or school:

https://escholarship.org/content/qt44q6n0mm/qt44q6n0mm.pdf

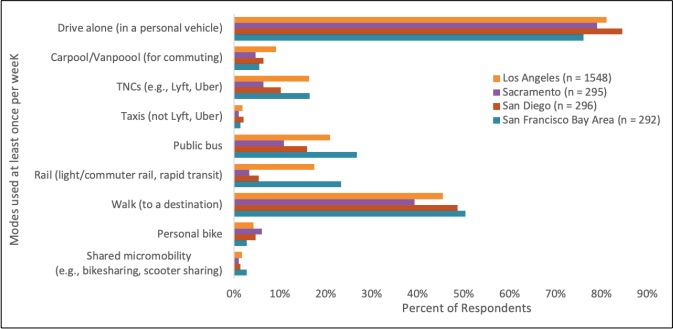

And the following travel profile gives us a clue about how they will get to where they are going:

https://escholarship.org/content/qt44q6n0mm/qt44q6n0mm.pdf

Finally, the new study notes that the pandemic has added to the allure of micro-transit pooling rather than mass transit.

Our Bottom Line: Fallacy of Composition

Sometimes what is better for the individual is worse for a group. In a crowded movie theater, if someone yells “fire,” then one person can run to the exit. But everyone cannot. Similarly, when prices soar, one retailer can stock up, sell more, and profit more. But if all sellers offer more to buyers, then competition brings prices down. Called the fallacy of composition, when everyone does something “good” together, it no longer has the same benefit.

For Uber and Lyft riders, it might be more pleasant to ride alone. But when everyone makes a similar decision, the downside kicks in. Ranging from emissions to congestion, we create what economists call negative externalities. Because a less attractive alternative–pooling–is the solution, society needs to figure out new incentives.

My sources and more: Thanks to Bloomberg City Lab for alerting me to the pooling paper. From there, this congestion study was also helpful.

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)