Baseball can almost return to normal this year with 162 games instead of 60. And, while stadiums will observe Covid reductions, they can have fans watching the games.

The fans though might see fewer home runs.

But before we look at the economics of the decision, let’s consider some home run history.

Home Run History

I can remember when Sammy Sosa and Mark McGwire were in a race to reach 62 home runs. The year was 1998 and McGwire won with 70. Although the 73 home run record from 2001 has not been broken, still we appear to have too many. The worry is that home runs make a game less interesting while stolen bases, a tag at third, and the race to first, grab our attention.

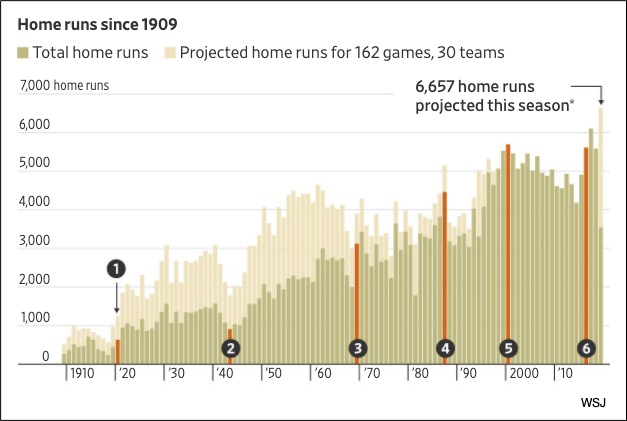

In 2019, Minnesota topped the Yankee 267 home run record with 307 when 15 teams–half the league–had home run records. Meanwhile, 2019’s 6,776 home run high was 1,191 more than the 2018 total. Correspondingly, home run records for teams, for the number of players, for individual players, all have soared. There used to be an average of 1.4 home runs in a game. Now at 2.5 it is more likely that we will see several.

The following graph is from the middle of the 2019 season. When it ended, the season’s 6,776 home runs exceeded the projection:

Our Bottom Line: Land, Labor, and Capital

As economists, we can look at baseball through a lens that sees the three factors of production. Like all goods and services, home run production comes from land, labor, and capital. It relates to the stadium (on land), to the players (labor), and to the balls (capital). So, we can ask which of the three changed when home runs spiked.

The baseball was one possibility. Surrounded by adhesive, a baseball has a core, the size of a golf ball, that is made of cork and rubber and wound in wool. Next comes the poly cotton, then the leather, and finally it’s stitched. The finished ball has to weigh somewhere between 5 and 5 1/4 ounces and have a circumference between 9 and 9 1/4 inches. A recent study concluded that a ball’s new stitch distance and its cork being closer to the center possibly diminished the “drag.” But they were not sure.

Officials also wonder if players’ new launch angles that send the ball higher have made a difference. In 2016, the average launch angle rose from 10.5 degrees to 11.5. Hit fast, a higher ball is more likely to become a home run.

With capital and labor having changed, the question was what to do now. The answer was the wool.

Baseball maker Rawlings said it will wind the ball’s wool a tad more loosely. Creating more “drag,” they expected to reduce the distance the ball could fly by a foot or two.

So, the land is the same and labor (the players) will continue their newer launch angles. But, by changing the capital, the wool will slightly “deaden” the ball.

My sources and more: Always interesting, the WSJ “Numbers Lady” had the baseball story. But, since WSJ is gated, you might want to look at cbssports, here and here, and ESPN. Then, finally and fascinatingly, this Washington Post article has all you could ever want to know about launch angles. (Our featured image is from WSJ.)