Why Coca-Cola Is Going After the Zombies

November 29, 2020

Why Inequality Might Have a $16 Trillion Price Tag

December 1, 2020Slicing away all of the complexities of economics, we wind up with no free lunch.

For an actual lunch, even when someone pays for the meal, we still give up the time that could have been spent elsewhere. Deciding if the lunch was worth the sacrificed time, we can consider the meal’s benefits, and what we would have gained from declining the date.

Similarly, as we debate the non-pharmaceutical interventions that could diminish the spread of COVID-19, the free lunch analogy becomes ever more important. We need to know the cost (what we sacrifice) of non-pharmaceutical interventions like mask mandates and business closings. Some new studies have given us up-to-date facts.

But first, we can look back to the 1918 pandemic.

1918 Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions

Approximately 550,000 individuals in the U.S., and 40 million worldwide, died because of the 1918-1920 influenza pandemic. At the time there were no antivirals nor any effective vaccines. But they did have non-pharmaceutical interventions.

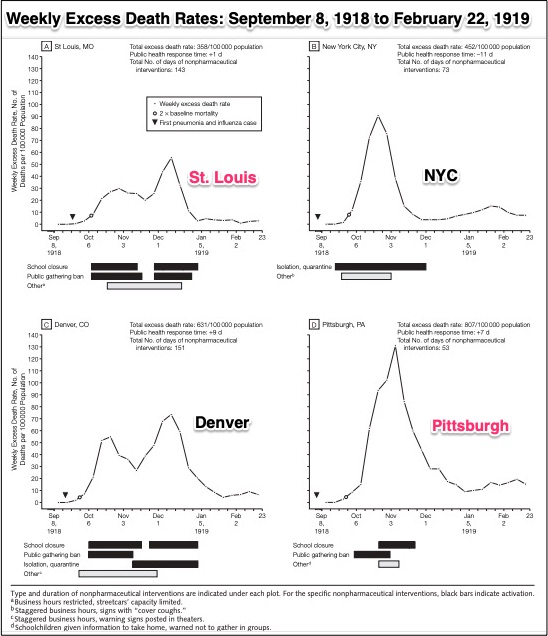

When researchers looked back, they uncovered massive variations in timing and selection among the interventions implemented by 43 U.S. cities. Below, especially when comparing St. Louis to Pittsburgh, you can see that interventions like closing schools, quarantines, and banning public gatherings do make a difference:

Discussing their conclusions, researchers suggested that non-pharmaceutical solutions do work. They emphasized that earlier, sustained, and layered interventions resulted in a reduced death rate, a delay in its peak, and lower peak mortality.

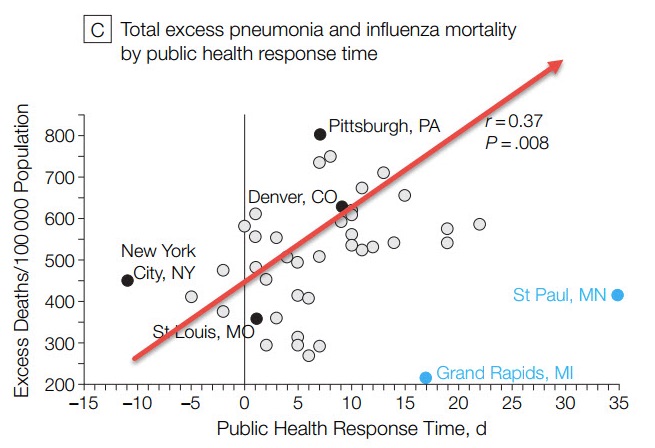

Summarized more simply, the following graph shows the positive relationship between mortality rates and the public health response time during 1918 and 1919:

2020 Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions

Now, contemplating some of the same decisions from a century ago, we know much more about their efficacy.

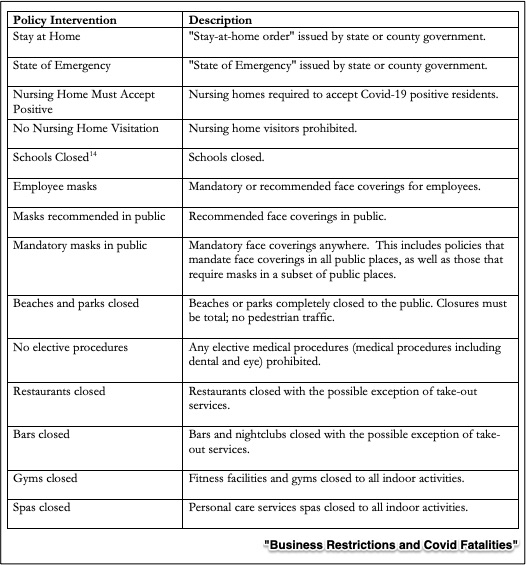

In a recent study, two Yale University economists used data for all U.S. counties from March through mid-October 2020 to compare non-pharmaceutical interventions and subsequent COVID-19 fatalities. The interventions ranged from mandatory mask wearing to business, school, park, and beach closures. Meanwhile, they focused on fatalities rather than case numbers because testing data was inconsistent.

Some of the results were predictable. Counties that mandated masks diminished their future fatality rate by 12%. Other policies with an impact of equal magnitude included stay-at-home orders, and high risk business closures for restaurants, bars, and gyms.

But there were surprises. Outdoor transmission at beaches and parks was higher than expected, perhaps because of the parties that encouraged closer sustained contact. Also, when spas, schools, and lower risk businesses (like book stores) were told to close, the impact could even have been counterproductive. One hypothesis is that people switch to higher risk activities when blocked from others. The study’s authors point out, for example, that the 100 person limit on groups could increase the likelihood of smaller gatherings. They reminded us of the perverse incentives that certain mandates create.

This is the full list of policy interventions. Each one brings to mind a slew of tradeoffs and their benefits:

Our Bottom Line: Tradeoffs

One of the authors of the recent multi-county study concluded that, “Mandatory mask policies seem to be as effective as policies that have higher costs.” The second researcher added that a mask recommendation, “simply doesn’t do anything.”

An economist would tell us that an opportunity cost chart is a handy way to focus on the tradeoffs required by these kinds of decisions. It names the opportunity cost–the sacrificed alternative–and the benefits of each alternative. It reminds us that looking forward, we have no crystal ball. To make a wise decision, we can only identify the current tradeoffs and probable benefits.

The following framework for a college decision can also be used to understand mask policy tradeoffs. Below, you can see that first you identify the alternatives. Then, you name each one’s likely benefits. The key to remember is that when you choose one alternative, you sacrifice the alternative and its benefits.

Below, the decision is to attend college. Getting a job is sacrificed as are its benefits:

Similarly, we can create a chart with a mask mandate and mask recommendation as the alternative decisions. One is the opportunity cost of selecting the other one. I let you take it from here. Do list the benefits of each alternative.

My sources and more: Thanks to my former student Mira for sending me the Yale pandemic study, this summary, and to Marginal Revolution for alerting me to the 1918-1919 pandemic paper. You might also want to read about this Kansas mask study.

Please note that today I’ve quoted some sentences from a past econlife post.

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)