In a new paper, three researchers ask why people believe they are affluent. Their questionnaire focused on “disposition” and “situation.” Disposition took the survey’s participants to the individual’s role while the situation believers thought the environment was more important.

Where are we going? From attitudes about affluence to income inequality.

The Study

The Participants

The 2017 survey’s 900 participants were from two income groups. Half came from the top 5 percent. The other was the general population. They wanted people to identify causes of economic outcomes. Only then could they compare the two groups and also see differences among the financially elite.

The study’s participants spanned the income spectrum:

The Questionnaire

The survey included questions about what they called “first and second order” attitudes. The “first order” was dispositional and situational. It asked about the importance of working hard and IQ, of family wealth, and luck. Then, a second batch dug deeper. They asked why certain people work harder. Is it genes, or family, or choices? Is it socialization? The answers matter because a dispositional bias means we believe that you and I control our affluence. But if it’s situational then you and I have less control while community and government can do more.

The Questionnaire

I’ve copied a part of the study’s questionnaire. A8.3 was a “first order” inquiry to establish participants’ dispositional or situational reasons for affluence. Then, A8.4 took a closer look:

The Results

The simple answer is that, more than any other group, the top one percent tends to believe the reasons are “dispositional.” They believe that economic success tends to be the result of intelligence, skill, drive, and genes. All income groups, though, believed the environment was also important.

But then, we start to see how the rich are different. Comparing the top 5 percent to the general population and then the 1 percent to those lower in the 5 percent is where it gets interesting. As you get richer, you increasingly believe that it was because of you. And, comparing disposition to situation, again we see a difference. The very top, more than everyone else, favors the ability of the individual over the influence of the situation.

But how unequal are we?

Income Inequality

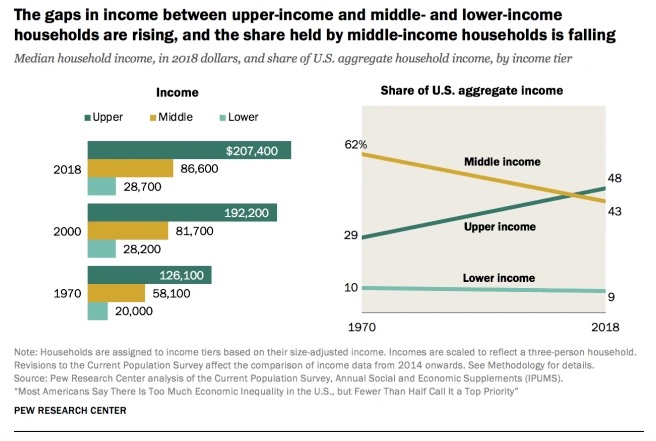

We’ve noted in past econlife posts that economists disagree on how to measure income. But today, let’s just look at what Pew Research has concluded.

After stagnating, household income has been growing:

Pew points out that some households in the middle income group rose and some fell. Some ascended to a higher income while other earned less:

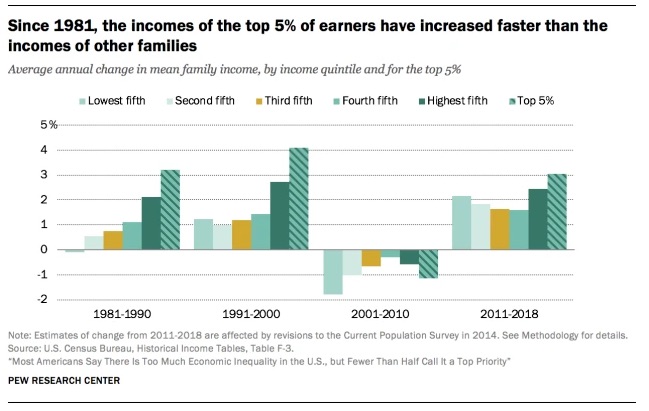

Still, because the biggest beneficiaries have been the top 5 percent, the income gap is bigger:

Looking at wealth, we can especially see the difference:

Where does this leave us? It takes us to a final section of the income attitudes study–to the politics. Its authors believe that knowing why we believe we are wealthy will help policy makers narrow the gap. The reason? All of us believe in “situational” causes. So perhaps, our policy makers can emphasize our commonalities when we discuss income inequality.

My sources and more: Thanks to Marginal Revolution for alerting me to this new paper on reasons for affluence. Closely related, Pew Research presented facts about economic inequality here and here. And finally, measuring inequality can take us to Lorenz Curves and Gini Coefficients.