Our Weekly Economic News Roundup: From Selling Records to Paying Athletes

June 15, 2019

What a Tax, a Ship, and a Road Can Tell You

June 17, 2019Recently, I was with a driver who depended on Waze. Trying to leave Manhattan as quickly as possible, he made every turn that Waze suggested. It appears that we weren’t the only ones. Every time we got to where Waze told us to go, there was gridlock.

We can explain what happened with the prisoner’s dilemma.

But first…

The Mapping Apps Problem

Before we had map apps, each of us independently decided the best route. Stuck in a traffic jam at the Holland Tunnel, I stayed where I was because I knew no other way. Other drivers though (like my husband), who could navigate the complex zigzag through Jersey City side streets, got to the tunnel far sooner than I.

Now though, even I can make it through Jersey City using an app. And that is the problem. When everybody can select the best route, it is no longer optimal.

The Institute of Transportation Studies at the University of California has tried to decide if we wind up with the socially optimal outcome when everyone knows the best route. Though not positive, in a 2018 article they suggested that autonomous vehicles, Uber and Lyft drivers, and the rest of us using mapping apps would make total congestion worse. One example is the rerouting caused by an accident. Everyone could create bottlenecks by clogging exit ramps and local neighborhoods. The aggregate result would be worse than if some of us remained in stop/go traffic on the highway.

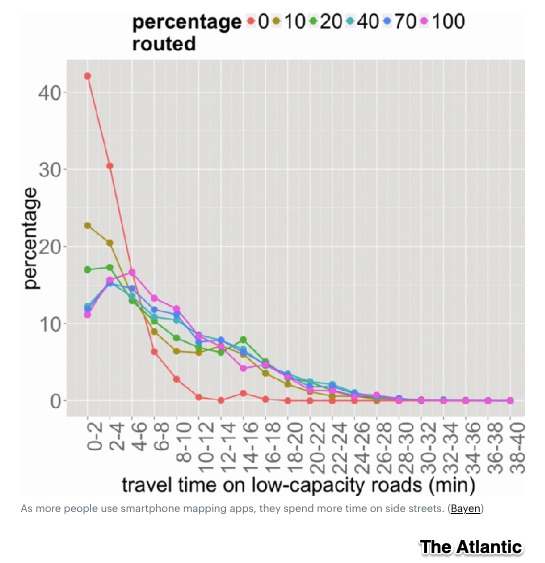

A growing problem is the time we spend on low capacity roads:

Our Bottom Line: The Prisoner’s Dilemma

Traffic experts have said we might be experiencing the prisoner’s dilemma when selecting a route.

The prisoner’s dilemma is a classic example of game theory because the success of what you decide depends on someone else’s decision. When two partners in crime are arrested, one knows that if he confesses and his partner does not, then he will go free. But if both keep quiet, they go to jail for one year. Because they are questioned separately, no one knows what the other has said. But the results depend on how much the other person admitted.

The prisoner’s dilemma? Keep quiet or confess.

The driver’s dilemma? Take the app route or stay where you are. And for me, it’s whether to zigzag through Jersey City.

My sources and more: The Atlantic took a closer look at the downside of Waze kinds of mapping apps. And we also looked last year. Finally, this paper has the math and the analysis.

Please note that several sentences describing the prisoner’s dilemma were in a past econlife post and our featured image is from the U.K.’s ONS.

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)